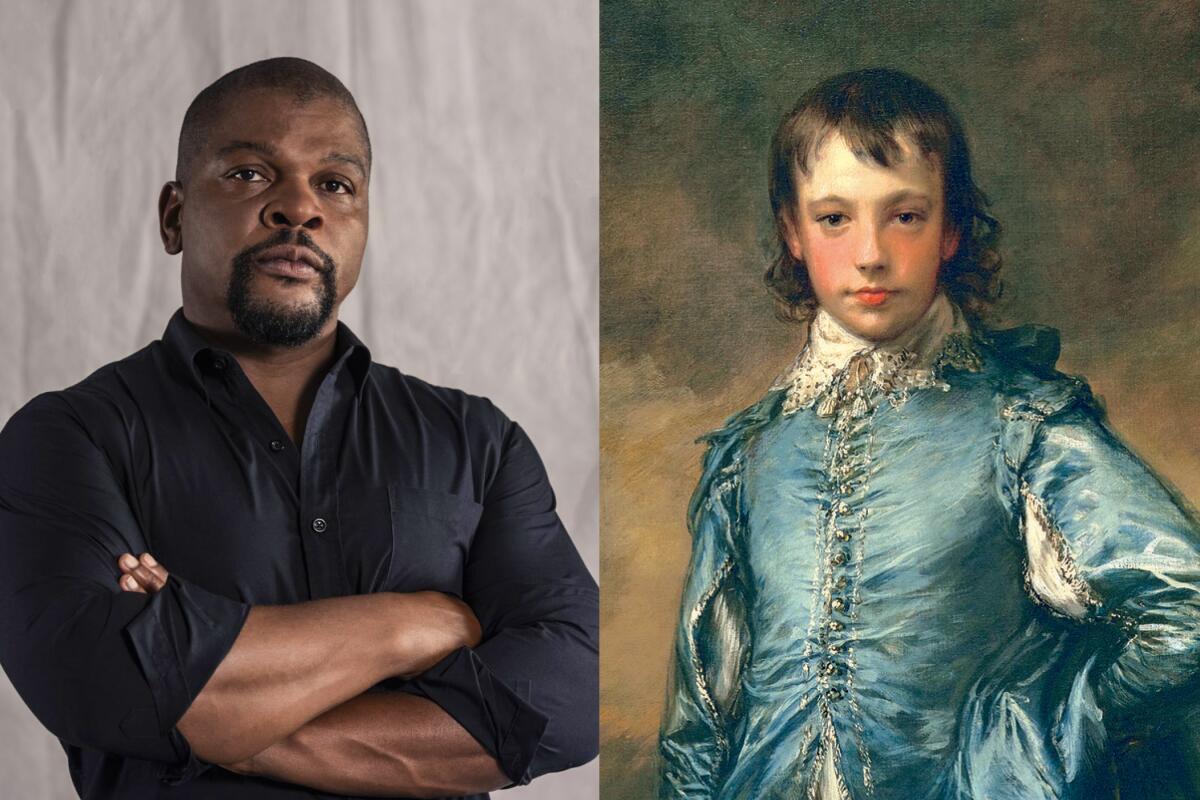

Kehinde Wiley commissioned to reimagine 18th century masterwork ‘The Blue Boy’

- Share via

Fall 2021 is shaping up to be Kehinde Wiley’s season in Los Angeles.

Not only will the artist’s 2018 portrait of President Barack Obama go on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in November but the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens has just announced a new Wiley painting to debut in October.

The Huntington has commissioned the artist to create a response to the most popular work in its art museum collection, Thomas Gainsborough’s 1770 masterwork “The Blue Boy.”

“It’s a portrait of an individual who occupies space,” Wiley said in an interview. In reimagining British Grand Manner portraiture — an ongoing thread in Wiley’s work — “I’m really indicting so much of the British aristocratic style of manifesting status anxiety.”

Huntington art museum director Christina Nielsen said in an interview that the museum is “absolutely thrilled” that Wiley is taking on the iconic painting. “Kehinde’s art practice is so steeped in art history,” she said, “but really helps us look at art of the past in ways that are very new and important today.”

The project is deeply personal for Wiley, who splits his time between West Africa and New York. When he was growing up in South Los Angeles, Wiley’s mother took him to the Huntington, where he was struck by the British Grand Manner portraits depicting 18th and 19th century figures draped in wealth and power. He also took educational field trips to the Huntington as a kid, and he admired the technical proficiency artists like Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds and John Constable showed on those canvases — how real the faces were.

But the young Wiley also felt somewhat alienated from the works, which didn’t feature Black or brown faces like his. That disparity, which he saw in so many museums growing up, would eventually inform his art practice, which addresses questions of representation, objectification, power and colonialism in art as well as historical inequities in cultural monuments.

“As a kid, I’d go to the Huntington and look at art because I was forced to. And then slowly it became something I fell in love with,” Wiley said. “Looking at those paintings gave me a sense of joy and wonder. But there was also a disconnect — the life I was having in South-Central Los Angeles and then these incredibly mannered and organized gardens and these portraits that hung on the walls. ‘The Blue Boy’ represents, for me, an ability to address the different standards with regards to who gets recognized, who gets praised.”

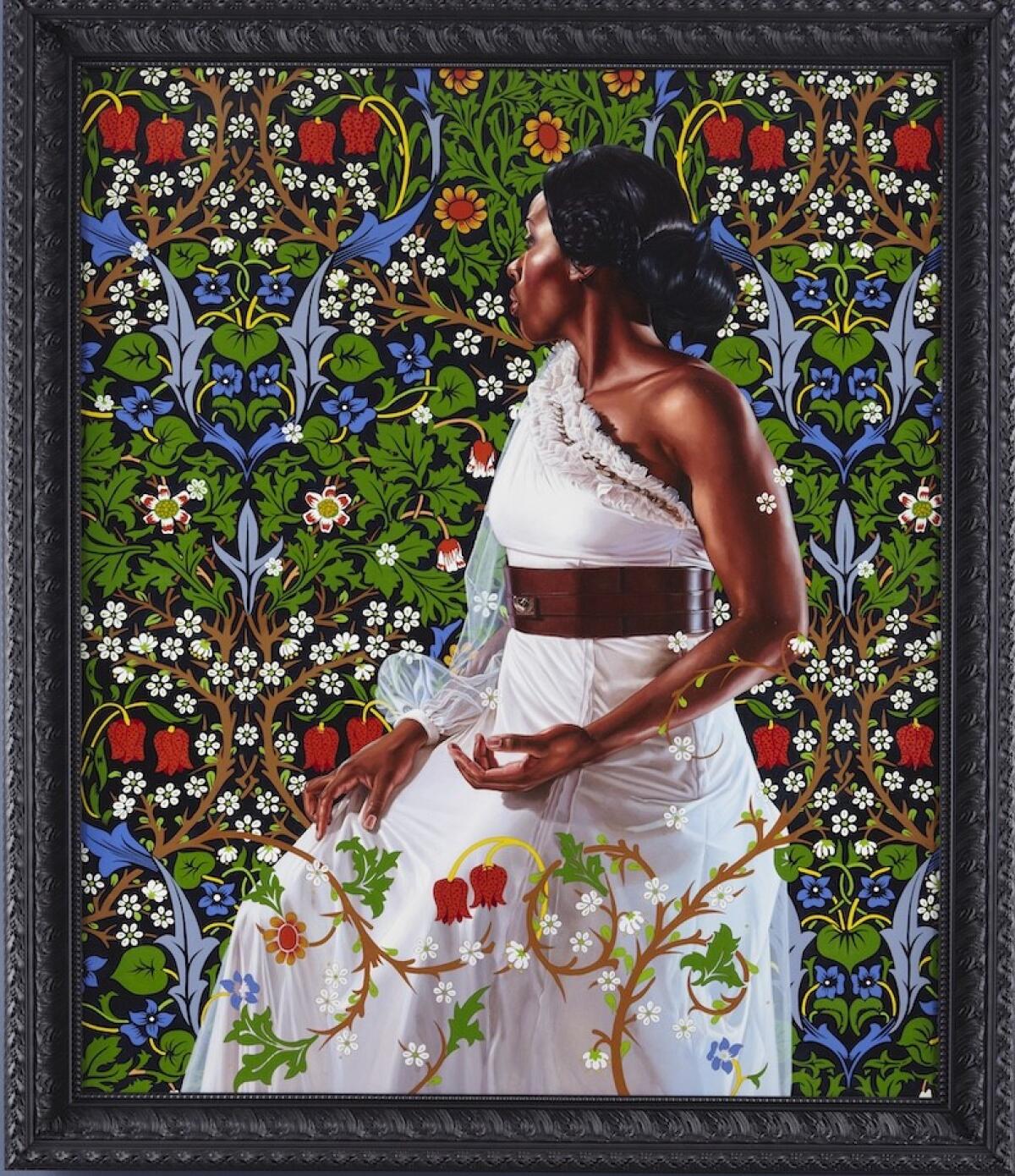

Wiley’s new work for the Huntington, which will be part of the museum’s permanent collection, is both historically referential and particularly immediate. It’s titled “A Portrait of a Young Gentleman,” which was Gainsborough’s original title of “The Blue Boy.” It nods to the technique and style of British Grand Manner portraiture but within an entirely different context. The model, in a similar pose as Gainsborough’s, is from Dakar, Senegal, where Wiley has a studio and painted much of the work during the COVID lockdown in 2020.

“It’s aesthetically and traditionally tied to a very mannered and known narrative surrounding power, dignity and beauty,” Wiley said. “And also the way that a society wants to figure a young man coming into age, coming into manhood.”

At the same time, he said, the new work “responds to global Blackness, not just a localized California sense of where we are. I wake up, there’s a global pandemic, what do you do, who do you paint? You paint Black and brown people surrounding you. And it turns out those same bodies that have no political, social, demographic relationship to the country that you come from are all indicted within this language of Blackness, this language of skin.”

Wiley’s painting — which will be on view at the Huntington from Oct. 2 through Jan. 3 — will hang where “The Blue Boy” now does, at the head of the Huntington’s Thornton Portrait Gallery. “The Blue Boy” will be relocated opposite the work, at the other end of the gallery, for the run of the exhibition.

Wiley hopes the facing portraits will spark a dialogue.

Whereas Gainsborough’s work is “a starting point,” the artist said, the new painting “arrives at a completely different set of cultural leanings by virtue of the way that we look at Black people, and Black boys, by virtue of the way that we change meaning and context. It’s only through these lenses that we understand the true impact of young Black boys not being seen as the babies that they are, the vulnerable people that they are, being systematically reduced to a type of menace.

“The troubles that surround negotiating Blackness in America,” he added, “are not just an American issue or project but rather a global question.”

“A Portrait of a Young Gentleman” isn’t the first time Wiley has reimagined British Grand Manner portraiture. His “Mrs. Siddons” (2012) — now in a private collection — was a response to Gainsborough’s 18th century portrait of the same name, at the National Gallery in London.

His “Portrait of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Jacob Morland of Capplethwaite,” (2017), from his “Trickster” series — now at the Yale Center for British Art — is a reimagination of English painter George Romney’s “Jacob Morland of Capplethwaite” (1763), in the Tate in London.

Wiley’s Huntington commission is meant to celebrate the 100th anniversary of founders Henry and Arabella Huntington’s purchase of “The Blue Boy” in 1921. But at a time when art museums around the country are facing a reckoning over equity and race — and considering the Huntington’s legacy of all-white leadership among senior staff — “A Portrait of a Young Gentleman” is also an opportunity for the institution to address its own history — and its future.

“We’re in the San Gabriel Valley, in L.A. County, very, very aware of the audiences that surround us — and I don’t just mean this particular ZIP Code,” Nielsen said. “Having the Wiley painting on the walls of our Thornton Portrait Gallery is absolutely a huge signal welcoming expanded audiences and helping people today connect to our historic collections.”

Nielsen noted that the Huntington has expanded its board of trustees with an eye toward diversity, adding three new members in 2021.

“The Blue Boy” underwent an 18-month restoration beginning in 2018 and was returned to the Thornton Portrait Gallery in March 2020. The painting is set to travel to London’s National Gallery in January, a decision that has some art conservators concerned. The more than 250-year-old work hasn’t traveled outside the Huntington since 1922, when it arrived.

“The journey to London from Los Angeles will be arduous for a delicate work of art,” Times critic Christopher Knight wrote in July. “Dangers lurk.”

Nielsen said the painting is safe to travel. “We’ve done a really thorough process of due diligence internally,” she said.

The Huntington and LACMA exhibitions are not Wiley’s only in-the-works L.A. projects.

Last week Destination Crenshaw — a $100-million undertaking to create a 1.3-mile cultural corridor on Crenshaw Boulevard reflecting and celebrating Black Los Angeles — announced that Wiley was among its seven inaugural artists. He’s creating a sculpture for the project that’s part of his “Rumors of War” series, a response to still-standing Confederate statues.

Wiley called all of his imminent Los Angeles exhibitions “a homecoming.”

“I am a son of the soil, I am from South-Central Los Angeles,” he said. “And this represents, for me, a readiness and a willingness to see my experience on the big walls, on the walls of institutions so that these stories are told.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.