The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“When people would ask me, ‘What do you shoot?’ I used to say ‘everything,’” artist Adam Davis says. “But now, I just tell them: ‘Black people. I mostly photograph Black people.’ And they get tense.”

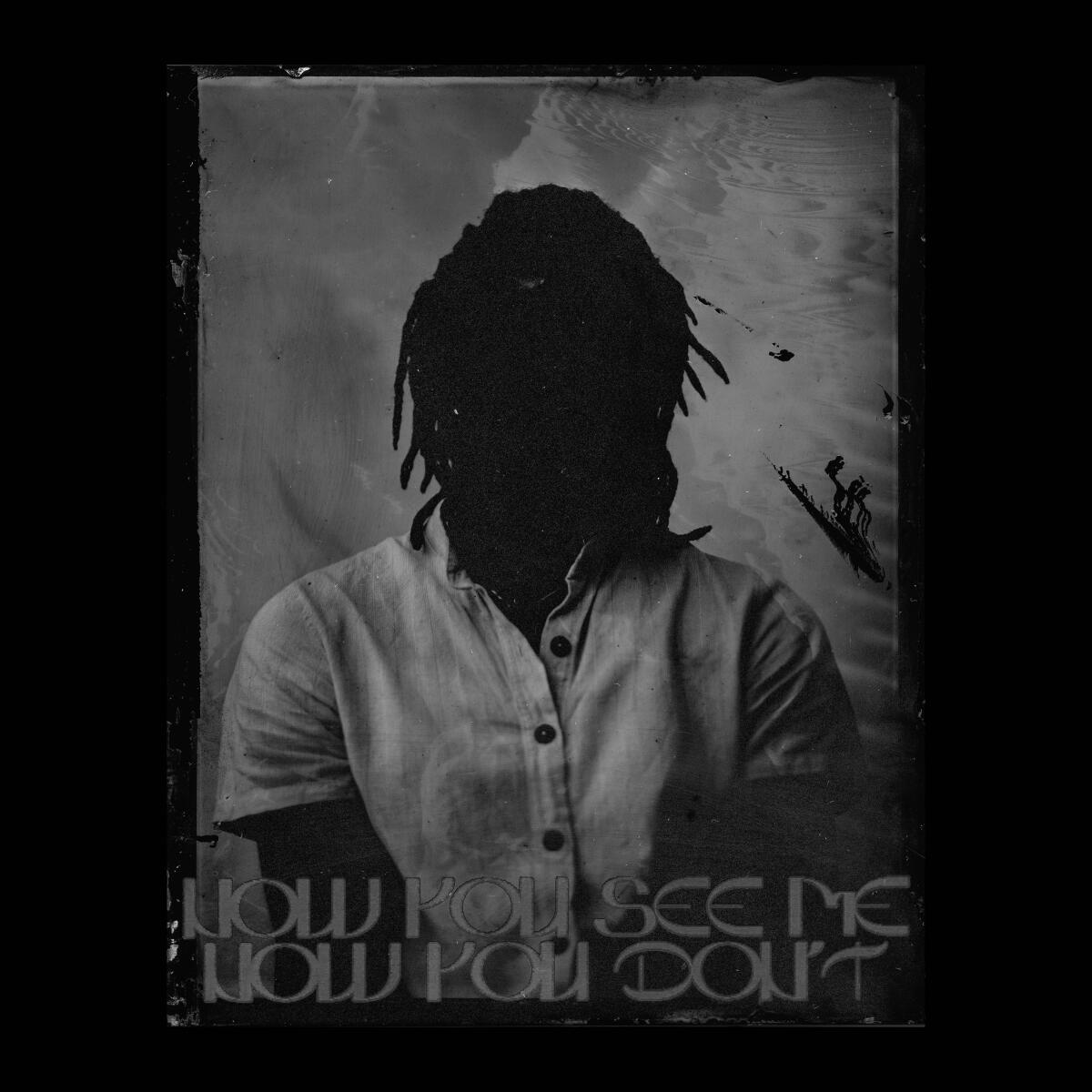

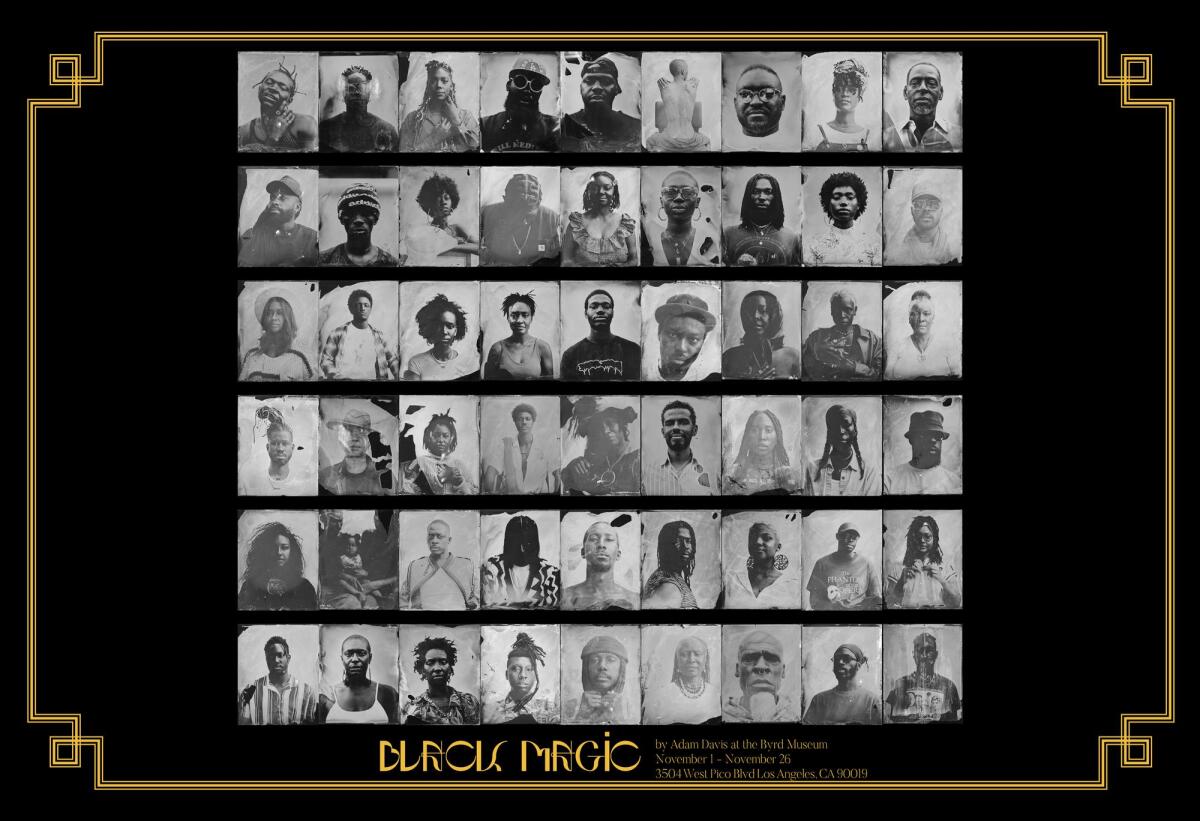

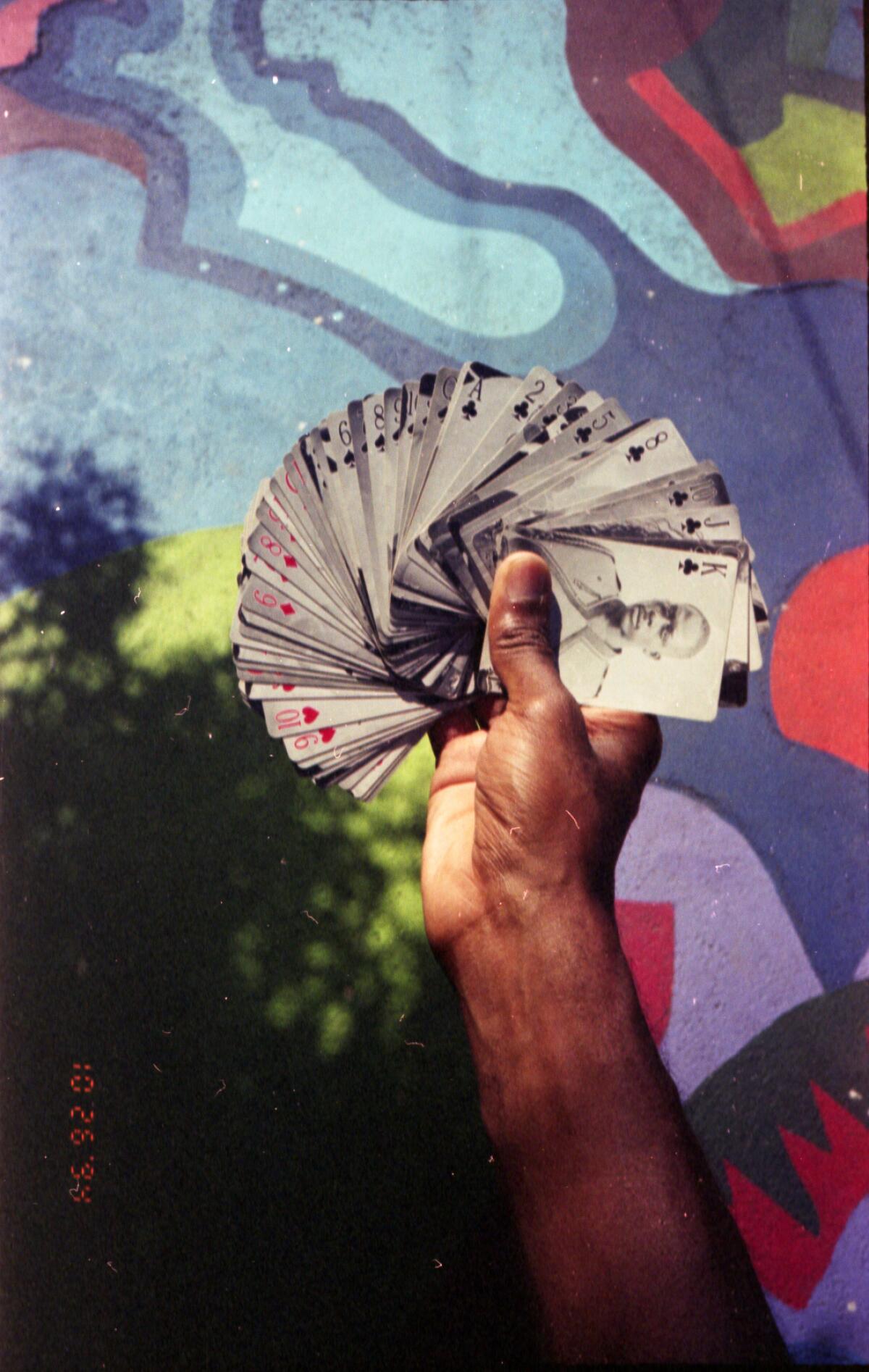

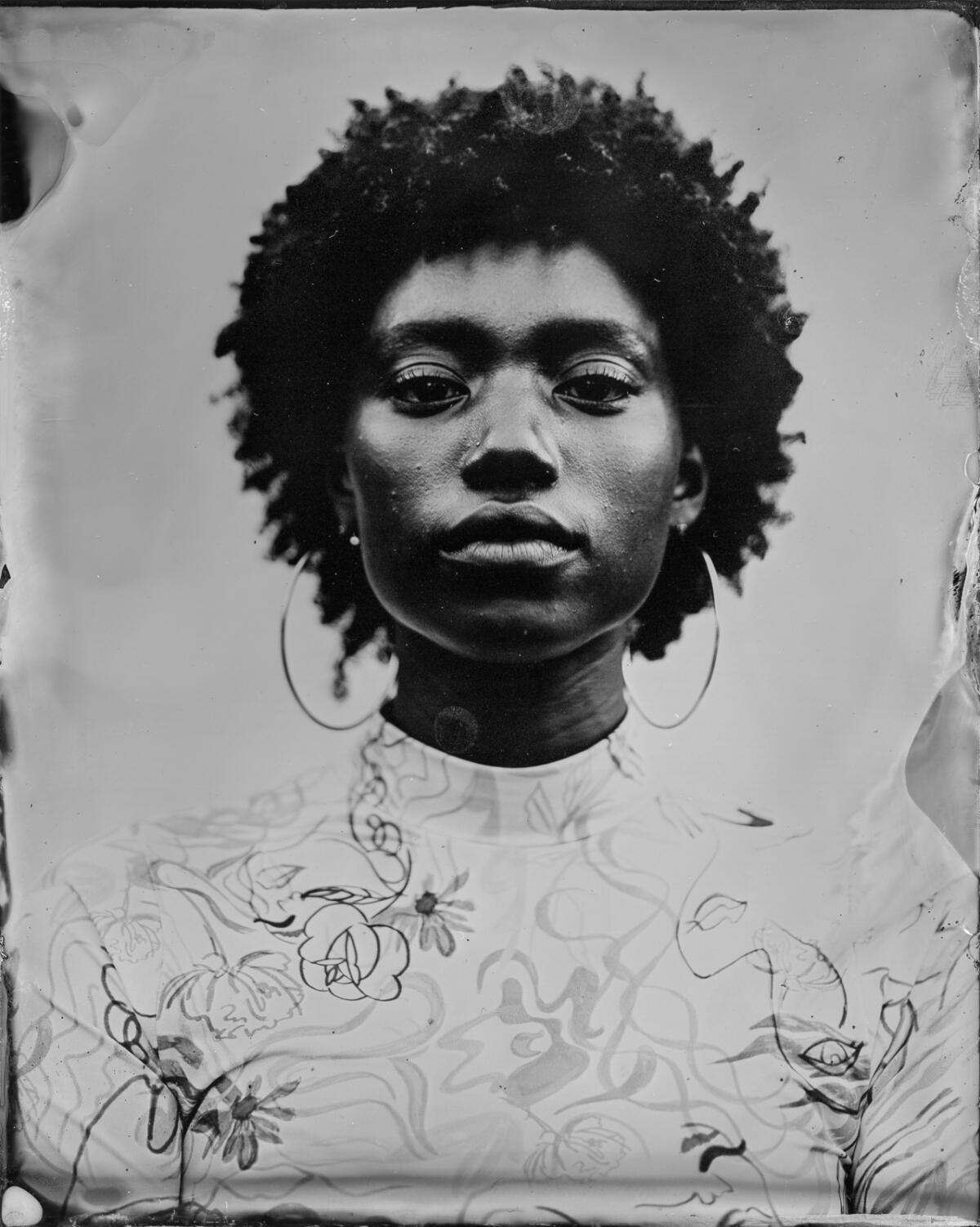

A production coordinator for the Black-owned L.A. bookstore Reparations Club, Davis, an artist and educator, employs the bygone medium of tintype portraiture in his work. For his second solo exhibition, “Black Magic,” Davis pinned 54 of these tintype images to white walls. The portraits captured the faces of Davis’ community, alongside custom card decks and skateboards. The weathered emulsion from the medium’s unique development process creates a distinctive vignette halo around Davis’ subjects.

Like photographer James VanDerZee, who once chronicled the people of Harlem, Davis takes a considered approach to documenting his contemporaries, posing individuals for portraits that celebrate their intrinsic beauty. “My first show [‘People Of Paradise’] was me asking ‘Where are the Black people?,’” he says, “‘Black Magic’ celebrates the Black people.”

After showing his portraits in November at Byrd Museum, a new art space in Mid-City, Davis hosted a tintype photography workshop at Photodom, a Black-owned camera store in Brooklyn. Davis is now embarking on a tour of historically Black cities around the United States, with stops in Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago and Tulsa. He will host pop-up tintype portrait sessions in his pursuit to make 20,000 tintype portraits of Black Americans — one of the largest contemporary archives of Black American portraits to date.

In the week leading up to the Byrd Museum opening, Davis meets me at the Mid-City bungalow he shares with his partner, Kai Daniels, an artist and activist. A pond babbles outside the window, and a garden of succulents climbs up to claim the wooden exterior walls. The pair moved into their home at St. Elmo Village, a 55-year-old Black-owned-and-operated community arts colony, just two weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the uncertain months that followed, Davis retreated to the darkroom that sits just outside his front door. The darkroom and the colony grounds were the vision of photographer and muralist Roderick Sykes, who, in 1969 at the age of 18, moved in with the mission to create a thriving creative enclave within the urban sprawl. By 2020 Sykes was in the twilight of his life, quietly living with Alzheimer’s a few cottages over from Davis and Daniels. Daniels had grown up adjacent to the St. Elmo community — Sykes and his wife, artist and administrator Jacqueline Alexander-Sykes, were a sort of extended family for her, she says.

When Davis moved to the neighborhood, Sykes was no longer able to communicate; Davis says he came to understand the gravity of Sykes’ legacy through the work he left behind — prints and sketches tucked into the darkroom’s desk drawers. “In my head I thought, ‘when I die, this is the bar,’” Davis recalls. “If I don’t have this amount of work and have impacted this amount of people...” He trails off for a moment, shaking his head lightly, “Yeah, like I’m sitting in this guy’s greatest art piece. It’s gonna make me f— cry.”

Davis, who was born in 1994, split his time between his family home on Long Island and his father’s parish in Brooklyn growing up. Davis’ father, a preacher, took up photography as a hobby, and snapped photos of Davis and their church family. His mother was a teacher. Davis attributes his career in art and education to his early access to creativity.

In 2016, Davis left New York for Los Angeles, a new city with little familiar community. “I was wondering, ‘Where are the Black people?’ I didn’t know any Black people, I didn’t know anybody that looked like me,” he recalls. Davis later began crafting a photo series of Black individuals holding birds of paradise, eventually comprising his first exhibition, “People of Paradise.”

During the pandemic, Davis taught himself how to develop film. He grew interested in the 1820s-era method of image making called wet plate collodion photography, or tintype. He tested and executed concepts for what would become his next exhibition — inviting friends and community members over to the complex to capture their portraits on tintype. Ultimately, 100 people would end up sitting for portraits.

The darkroom evolved into a sanctuary for Davis, particularly during the upheaval of COVID-19. During the pandemic, Davis lost several loved ones. “That room means a lot,” he says of the darkroom. “I would go in there and just peak depression, peak suicidal thoughts, like screaming top of my lungs and no one could hear me. I could just go in there and disappear,” he says.

While processing their grief, Davis and Daniels decided to decamp to Oaxaca, Mexico, in December 2020. Locked down in Oaxaca, Daniels virtually attended her masters classes at the Southern California Institute of Architecture. She took a course by Kahlil Joseph centered around the concept of Black town ownership and what that can look like from an architectural and anthropological perspective. “You can’t talk about art and culture in Los Angeles without mentioning Kahlil Joseph,” Davis explains. “He taught [the class] how to make my favorite piece of art [BLKNWS, a video installation] and I was like, ‘Babe, I got to know how he does this.’” Daniels began forwarding Davis recordings of her class sessions.

When Davis returned to Los Angeles, he looked at the tintype portraits he had taken throughout the pandemic with a renewed interest. Davis began imagining a future world, one where the tintypes resembled “futuristic ID cards.” He selected 54 portraits: the number of cards in a deck (jokers included). In the exhibition catalog of “Black Magic,” Davis writes: “What was once just an exercise in curiosity and discipline, blossomed into this extraordinary celebration of all the people and places I hold dear.”

In tandem with the exhibition and the book, he created a series of promotional videos, paying homage to Joseph’s signature two-channel video format. “Some of the prompts from the class were just about imagining the future and documenting movement — capturing places through Blackness,” he says. “It really forced my thinking outside of the box I’ve been in. I put myself in the shoes of someone who makes films.”

In April 2021, Sykes succumbed to his years-long battle with Alzheimer’s. Davis channeled Sykes’ resolve as he set out to find a venue for his vision, recalling how Sykes once described his approach to art-making: “Don’t wait for validation from them and they… This is what you can do with what you have, today is the best day. Yesterday’s gone and tomorrow ain’t got here yet.”

When plans to exhibit “Black Magic” at a dream space fell through, Davis contacted Brittany Byrd, a young artist, stylist, influencer and the owner of Byrd Museum. Byrd is a recent graduate of Parsons and, like Davis, had experienced setbacks over the years while pursuing her artistic vision. “When I was told, ‘You’re not Black enough to do the things you want to do in art,’ that’s when I stopped looking for validation,” she says. When Davis approached her with the deck for “Black Magic,” she knew his work felt right for the space.

With “Black Magic,” Davis imagines a future which centers and celebrates Black individuals and culture. To do so, he says, he had to unravel his own experiences and critique areas he perceives as regressive within the community. “You can’t mention Afrofuturism without talking about queerness,” he explains. Davis began contemplating his own relationship to queerness while making the portraits for “Black Magic” and also realized a majority of his subjects in the series identified as LGBTQ. “It’d be a disservice [not to talk about it] and realistically it’d be a lie.”

This spring, Davis will spend two weeks in each city he visits on his tintype tour. “It’s not a pop-up,” he says. “It’s a show up and hang out.” Davis will make two portraits of each person who sits for a portrait, keeping one for his archive (and future exhibition) and giving the other to the subject; “an artifact of their existence,” he calls it.

Davis hopes to complete 500 portraits on this tour, which will put a dent in his ambitious 20,000 portrait pursuit. “If you show up and you’re Black,” he says. “you get a portrait.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.