Review: What LACMA’s collection of Spanish American art, 1500-1800, says about the world today

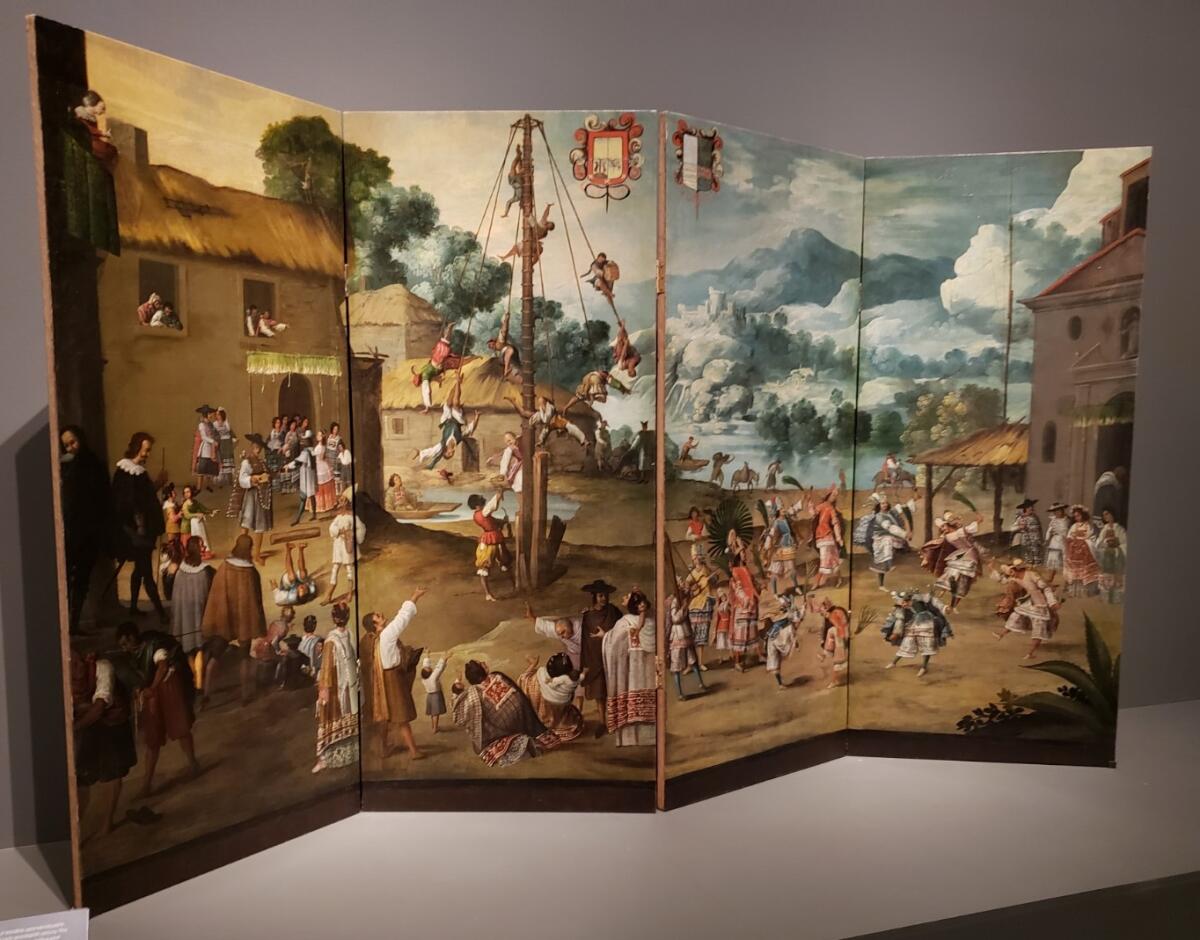

A painted four-panel folding screen that stands 6 feet tall and 10 feet wide is a touchstone for “Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500-1800,” a gorgeous new installation of permanent collection works at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. There are 90 objects, including paintings, sculptures and decorative arts, mostly from Mexico but from Guatemala, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Peru and Brazil as well. The painted screen, made in Mexico during the second half of the 17th century, is a profound international document — an exquisite “archive of the world” all by its magnificently sophisticated self.

First, as a painting in oil on canvas, the work reflects a legacy of European artistic tradition unknown to pre-Hispanic Mexico. It shows a wedding party, probably in or near Mexico City, but the mysterious yet voluptuous blue and white landscape backdrop is a kind of Flemish-style stage set for the events unfolding in the detailed action out front. Perhaps it was made in Mexico for export back to Spain or the Spanish Netherlands, where it would need to court local taste.

Second, as a free-standing folding screen (called a biombo), it’s like the ones that might be found in a prosperous house in China or Japan but certainly not on the Iberian Peninsula or in Italy or France. Paintings never assumed this form in Europe. The work represents the arrival and flourishing of Asian cultural inheritance into New Spain along trade routes from Manila, Philippines, to Acapulco on the Pacific coast. If the screen was for export, a European patron would be getting something delectably unique.

Finally, as an elegant, eloquent and brilliantly composed depiction of festivities surrounding a Catholic wedding between an Indigenous husband and wife in New Spain, the imagery embodies the complex intersection of cultures in the centuries following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. The painting commemorates a Christian sacrament, but it is framed with Native dancers and an Indigenous sport where men suspended on ropes from their ankles or waists whirl around a tall wooden post — sort of an extreme maypole.

Mexico, Spain, Flanders, China, Japan, the Philippines — multiculturalism has been around for hundreds of years in the art of Spanish America, given the sprawling global empire carved out by Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella and their Habsburg and Bourbon successors. We like to think multiculturalism is new, but it’s not. The artist, whose identity is unknown, interwove them seamlessly in his painted screen. (And it’s almost certainly “his,” as women were kept from working in the studio then.)

Each of the four panels is a separate zone of activity. From right to left, we see the wedding party, then the dancers, on to the flying pole and finally the assembled guests. Together they establish a continuous scene of marvelous, carefully observed revelry. Since the screen stands upright on the floor, the shifting light and physical zigzag of its four panels add to the depiction’s lively sense of animated action.

The current installation is the first time the screen has been shown correctly, standing upright, which is how it was meant to be experienced. Acquired in 2005 from a Portuguese royal palace 40 miles north of Rio de Janeiro, it was always shown at LACMA hanging flat on the wall, like a painting. (It was also hung that way in the palace: A photograph is included in the indispensable catalog, which functions as an essential and most-welcome guide to the museum’s important permanent collection of art from the viceroyalties of Mexico and Peru.) Recent conservation work made the reorientation possible, and the difference is decisive.

More than half the works in “Archive of the World” — 46 — are paintings, and the quality is uniformly high. There’s room for growth, of course. Talavera poblana pottery, with its beautiful fusion of Chinese, Moorish and Indigenous influences, is unrepresented, and an elaborate altarpiece would be a good addition, if tough to find. (One wall in the show features a group of smaller religious paintings, perhaps meant to evoke a multipanel altarpiece.) Few American museums have significant collections of what used to be called Spanish Colonial art, but of those that do, LACMA’s is a standout.

That it has been assembled in just 16 years under the careful guiding eye of curator Ilona Katzew is remarkable. (The collection’s first two acquisitions — the extraordinary folding screen plus an exquisitely refined badge of painted copper, a Nativity image worn as part of a nun’s habit, by the great 18th century religious painter José de Páez — were purchased in 2005.) Notably, responsible deaccessioning made it possible.

LACMA, like many museums, has almost nothing in the way of acquisition endowments with which to buy art. What it did have, however, was an unrestricted 1997 gift of some 2,000 works, mostly Mexican Modern, from art dealers Bernard and Edith Lewin (since deceased). Not a formally curated collection of paintings, sculptures and drawings, it represented ad hoc inventory that remained from the Lewins’ galleries of Latin American art in Beverly Hills and Palm Springs. The most important of those works, including paintings by Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Rufino Tamayo, were retained by LACMA, while others were deaccessioned and sold to create an acquisition fund for Latin American art, both present and past.

Ironically, Mexican Modernist art allowed for the establishment of a brilliant museum collection of Viceregal art from Spanish America — ironic because Rivera and his radically splendid cohorts celebrated folk art and the art of the pre-Hispanic past almost exclusively. Colonial art? No way. They had little use for the cultural production of the region’s brutal colonizers, including its religious subject matter. The studied and admired history of the region’s art pretty much went from before 1500 to after 1800, with a glaring 300-year gap in between.

Western art historians also tended to ignore it, incorrectly regarding artists like Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768) or Vicente Albán (1725-unknown) as deficient, compared to European painters. They were cast as copycats or as artists who tried and mostly failed to keep up, rather than as exceptional talents who developed distinctive aesthetics that were not only specific to their multicultural milieus in the Americas but that thrived because of the differences.

The 300-year gap has been filling in. Regard for the art of Spanish America has been on the rise in recent decades, having taken a big leap in 1990 with “Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries,” the extravagant Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition whose organization benefited from input from Mexican poet and diplomat Octavio Paz, who coincidentally won the Nobel Prize in Literature that year. (The show traveled to LACMA.) I would argue that interest has been subsequently cemented by the vivifying tensions between multiculturalism and white supremacy coursing through the art, which speaks so urgently to us today. It shows us something about where we’ve come from.

Take the two most recent acquisitions, both added to the collection last year. One is an extraordinarily refined polychrome sculpture of “Saint Michael Vanquishing the Devil” from late-18th century Guatemala, the triumphant saint standing on the beast’s back with his silver cross doubling as a spear poised on the devil’s head. The other is a late-17th century Cuzco School painting from Peru, which shows Habsburg King Charles II, sword drawn and backed by two archangels (including Michael), defending from attack a Eucharist displayed inside a spectacular jeweled monstrance.

Not by accident, the sculpture’s glorious St. Michael is a rosy-cheeked, whiter-than-white European, while the subjugated devil bears dark, swarthy, mustachioed features of a grimacing Indian. As for the painting’s exalted Eucharist, it’s under threat of being toppled from its elevated position atop a Greco-Roman column by two dark, menacing Ottoman Turks and a Protestant heretic, while an idealized, virtually porcelain-skinned King Charles stands preternaturally serene. Essentially the same racially and spiritually coded messages are sent by works made a century apart in Spain’s two viceroyalties, north and south.

Gilded and beautifully crafted, both emphasize luxurious two-dimensional surface decoration. The styles couldn’t be more different from the complex spatial elaboration seen in European Baroque sculpture and painting, with their emphasis on volumetric figures deployed in a spiraling infinity of deep space. In those centuries, Europe was busily sailing out into the world to colonize what it could, a spatial journey reflected in its three-dimensionally extravagant art. For artists working in the colonized Americas, there was no need for that; they weren’t traveling anywhere.

Instead, they drew on Indigenous visual traditions from textiles, metalwork, pottery decoration and other sources at hand. In short, European Baroque depends on the elaboration of space, while Spanish American Baroque demands the elaboration of surface. At LACMA, a stunning silver monstrance, sumptuous church vestment embroidery, boxes inlaid with bone and tortoiseshell, and carved wooden trays painted in a dense profusion of floral patterns draw the comparison.

These days, the art in “Archive of the World” looks more relevant to contemporary life than ever before. Maybe the best place to see that is in the “Virgin of Guadalupe,” arguably the most famous image of the colonial era.

The iconic painting of a young woman, head bowed, dressed in a spangled robe and standing on a crescent moon, is represented in two versions hung side by side. One, likely painted by the father-son team of Antonio and Manuel de Arellano, is a meticulous 1691 copy of the original that is still venerated in Mexico City’s Basilica of Guadalupe. The other, from a quarter-century later, is by Antonio de Torres, a member of a large family of painters. (Torres’ dramatic and monumental canvas “The Elevation of the Cross” is also on view nearby.) One picture is slightly larger than the other, and vignettes in the roundels that surround the central figure of the Virgin are different. But the Virgin herself is virtually identical, right down to the slightly bent little finger of her praying left hand.

That’s probably because a third clever artist, the great Afro Mexican painter Juan Correa, son of a Spanish surgeon and a freed Black woman, produced a wax-paper template from the original so that accurate copies of the miraculous image could be reproduced by others. Demand was high for them. Today, seeing the Virgin of Guadalupe doubled on the gallery wall is like seeing paired versions of Andy Warhol’s famous “Marilyn Monroe,” both reproduced from the same silkscreen. Then as now, demand is a formal driver of artistic invention.

'Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500-1800'

Where: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd.

When: 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Mon, Tues, Thurs; 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fri.; 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Sat. and Sun. Closed Weds. Through Oct. 30.

Contact: (323) 857-6000, lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.