Brody Stevens’ 818 Day is a reminder of the mental health struggles comedians still face

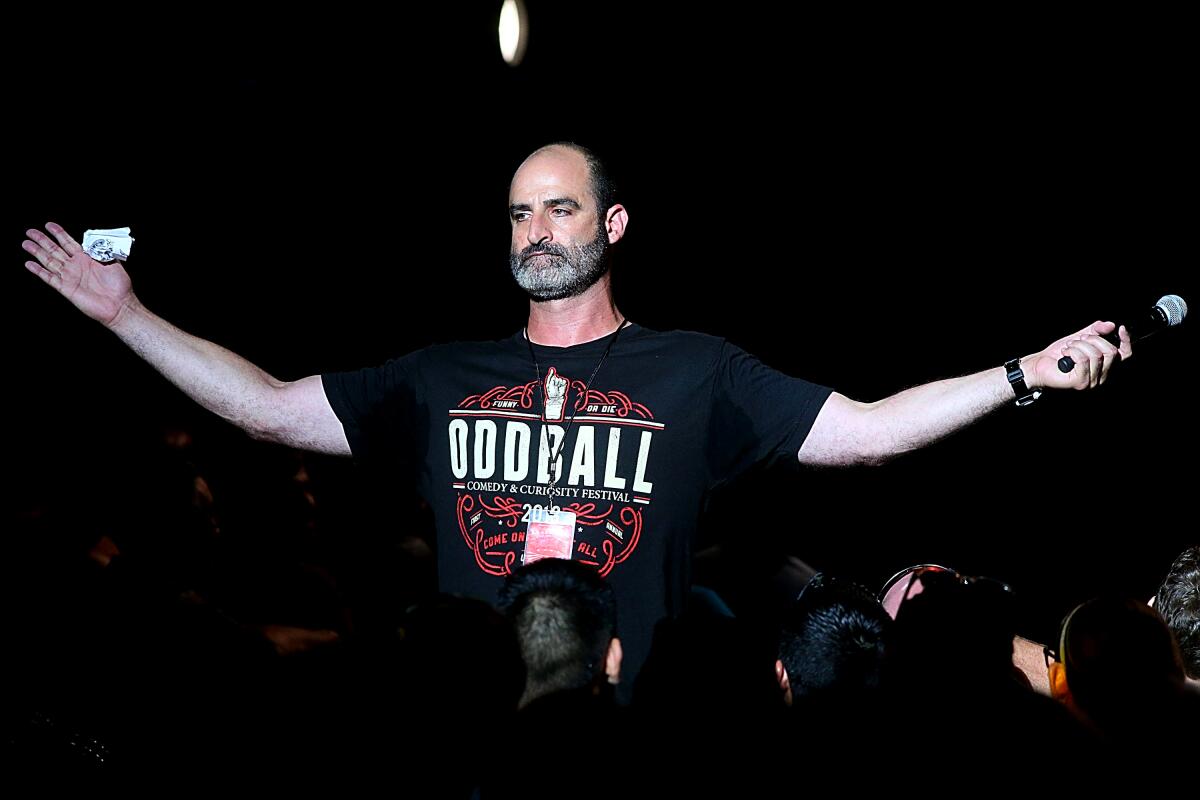

Comedian Brody Stevens was found hanged on Feb. 22, 2019, dead at age 48, and the impact on the comedy community was immediate. Comedy clubs and festivals across the country felt greater responsibility to promote mental health resources. The topic of depression shifted from onstage joke fodder to serious offstage conversation. Fellow comedians gathered for an informal 818 Walk in Stevens’ honor that August, named for the San Fernando Valley area code of his childhood that he would often reference in his self-deprecating bits. In 2021, the second installment of 818 Day included the official dedication of an L.A. Parks Foundation memorial bench in Stevens’ honor, funded by Mauricio Alvarado of Rockin Pins from a design he’d created with Stevens before the comic’s passing.

Since 2019, Stevens’ sister, Stephanie Brody, recalls, “I lost count of the number of emails I received from people saying my brother was the first — and sometimes only — person who reached out and helped them when they were first starting out.… We always knew my brother was a nurturing and kind person. But the stories we read took what we knew about him to a whole other level.”

On Thursday, Aug. 18, at 8 p.m., the late comic’s home club, the Comedy Store, will hold a special Brody Stevens 818 Day show, followed by Saturday Aug. 20’s now-annual Brody Stevens Festival of Friendship 818 Walk in Reseda.

This year’s event has partnered to benefit Comedy Gives Back, a 501(c)(3) charity aiding performers in need of mental health support and addiction treatment. After Stevens’ death, the organization shifted its focus from gala fundraising to grass-roots outreach, bringing awareness to the darker side of the seemingly lighthearted occupation.

“Brody always exposed all sides of himself to the audience,” says Zoe Friedman, a longtime producer/booker who founded Comedy Gives Back with Jodi Lieberman and Amber J. Lawson in 2011. “His comedy made you feel like you were hearing what was going on inside of his brain, and that he was articulating it in real time. He gave audiences a peek behind the curtain of his inner workings.”

Friedman says her favorite part of the Festival of Friendship is the love from comedians and fans who want to keep remembering Stevens and, in doing so, bring the issue of suicide to the forefront. “If we don’t talk about it, we perpetuate the stigma around it,” Friedman says. “The more we can talk about Brody and why we lost him, I believe and hope we can help others.”

The Saturday festivities begin with the 9:30 a.m. unveiling of a new “Brody Forever 818” mural at Firehouse Taverna restaurant (18450 Victory Blvd.) with Los Angeles City Councilmember Bob Blumenfield, Stephanie Brody and additional family members. At 11 a.m. a 5K walk starting at Reseda Park (18411 Victory Blvd.) takes participants across the Los Angeles River and past Reseda High School, where Stevens was a star pitcher on the Regents baseball team. Registration is $50 in advance or $60 day-of starting at 10 a.m. and includes a gift bag. Afterward, a 1 to 3 p.m. celebration at the memorial bench site will feature speakers, comedian pals, a raffle, a photo booth, food trucks and music from DJ Dense of the L.A. Clippers. Merchandise including shirts and Rockin Pins’ enamel likeness of Stevens will be available.

The Valley native was born Steven James Brody on May 22, 1970. He played Division I baseball at Arizona State University, though an arm injury ended a promising career as a pro. Stevens spent time developing in the Seattle and New York City comedy scenes before returning to L.A. Tall and fit throughout his life, he remained a staunch proponent of physical activity and healthful eating.

In L.A., Stevens became known as a go-to warmup for series ranging from Fox Sports’ “The Best Damn Sports Show Period” and E!’s “Chelsea Lately” to Comedy Central’s “The Jeselnik Offensive” and MTV’s “Ridiculousness.” As Stevens proudly noted onstage of his film credits, “‘Hangover,’ in it! ‘Hangover II,’ in it! ‘Due Date,’ in it! Cut out of ‘Funny People’ …”

His biographical one-liners (“I’m intense! I get BO in the shower!”) tended to sound more barked than told. Getting confrontational with audience members sporting deer-in-the-headlights looks became peers’ favorite part of any evening. Despite spouting catchphrases like “Positive energy!” or “Push and believe!,” those close to him knew his wide smile could feel unmistakably forced.

Stevens described himself as a troubled kid. “I was touched. But not by an angel,” one of his most popular jokes began. “The perp was supposed to get three years, but the judge gave him six. Why? Because I was molested in a construction zone.” It couldn’t have all been wholly true, but as a talent known for brutal honesty, could it?

He battled depression from an early age, going on and off different medications from his 20s onward. Audiences and interviewers alike were often informed that he’d developed “adult-onset autism.” In 2010, while filming his docuseries “Brody Stevens: Enjoy It!” with executive producer Zach Galifianakis, he was hospitalized for 17 days at UCLA Medical Center’s psychiatry wing and diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

His 2017 special, “Live From the Main Room,” filmed at the Comedy Store, divided online comedy fans. Despite acclaim as the “Prince of Periscope,” negative social media interactions frequently leveled him. Stevens had resumed taking anti-psychotic medications shortly before his death.

Stevens’ sister, Stephanie, who occasionally appeared as a foil in his jokes, says he brought a much-needed awareness of mental illness and the challenges that come with it to the comedy industry.

“He put a face on the disease and put it out there for all to see. He wanted people to see there isn’t anything to be embarrassed or ashamed about,” she says. “I see comedians talking more openly about their own mental illness struggles and how they’ve handled it. I see comedians being supportive of one another and being there for each other. I know he’d be proud of the impact he’s made … just as proud as our family is of him.”

Even in the lead-up to this year’s Festival of Friendship happenings, reminders surfaced that the process toward destigmatization remains far from complete. On Thursday, July 14, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline publicly announced its 10-digit 800 number would change to the simpler 988. Later that same evening, the body of popular scene staple Jak Knight, a highly successful actor, producer, writer and stand-up, was discovered on a Boyle Heights embankment with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. Like Stevens, Knight was known for his upbeat mood and welcoming nature.

“Telling strangers things about yourself sounds more like a therapy session than a job. But that’s the job they pick. It’s not for everyone,” says Friedman. She cites family dysfunction, trauma, depression and general feelings of otherness as psychological reasons performers may be drawn to the profession.

“Additionally, their lifestyles can be very hard and isolating: being on the road, sleeping late, long stretches of time during the day by yourself to fixate and worry about things. Comedians help make audiences feel better by allowing us to laugh. I hope that the process of telling their jokes can help them feel better as well. It only seems fair, right?”

Or, as Stephanie Brody puts it, “The job of a comedian is to make people laugh. People presume if someone is funny, they must also be happy. That’s not necessarily true.... Struggles comedians experience are often masked by the sound of laughter. The comedy world is often overlooked when it comes to mental health awareness because of this. Opening up and talking about mental illness helps take the stigma away. I have noticed a gradual shift in that way of thinking. But our society needs to get to a place where mental illness isn’t something to be ashamed of. I think we are headed in the right direction, but we still have a long way to go.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.