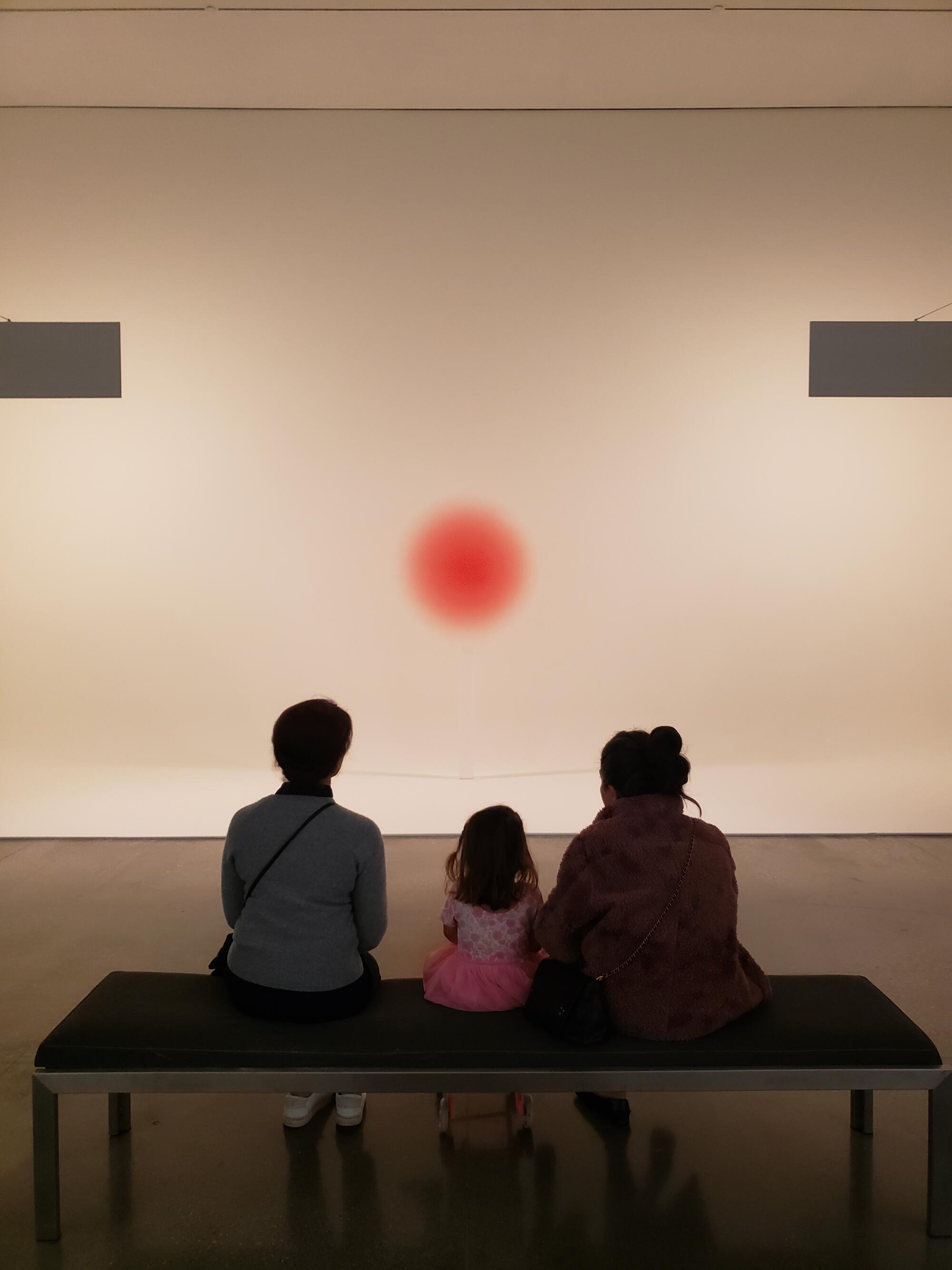

Illustration by Jason Allen Lee / For The Times (Art renderings are not reproductions of LACMA collections)

Do you miss LACMA? I do.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art launched more than 60 years ago as an encyclopedic place to collect and explore global art history from the last 3,000 years. Now, history has largely been abandoned.

Most of the museum’s program of exhibitions and installations is limited to art made between the mid-19th century, when the rambunctious emergence of Modernism in Europe began to upend everything, and the present day. And most of that has been dedicated to art since 1945. LACMA has transitioned into a de facto museum of contemporary art.

How lopsided has the program been? Of the 11 shows on view at the museum last year, just two centered on historical art. The other nine — 82% of the program — presented art of the modern era.

The tilt was not a pandemic anomaly, either, determined by the difficult scramble around exhibition schedules that all museums encountered. Go back further. Scroll through the museum’s website listing more than 70 offerings during the last five years, beginning before COVID-19, and you’ll find a similarly lopsided ratio.

Look back a full decade, even, and the numbers are not much different. Of more than 200 listed shows and installations, three-quarters were modern and contemporary art. Of that, art made since 1945 accounted for considerably more than half. Art from the other 2,922 years made occasional guest appearances.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

It’s not as if the city needs a museum for recent art — or, should I say, needs another one. Downtown there’s an important Museum of Contemporary Art with a storied, if sometimes administratively wobbly, history. Across the street is the flashy Broad, a rich man’s treasure vault overstuffed with paintings and sculptures, especially Pop art and its descendants, from the 1960s and after. At UCLA, the savvy Hammer Museum has catapulted into the ranks of the nation’s most ambitious university art museums by showing and collecting the art of our time almost exclusively.

Add in the regional plethora of smaller nonprofits like Craft Contemporary; California African American Museum; Beyond Baroque; LAXArt; the Armory; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and many more, plus the still-growing cadre of commercial galleries across the city, now numbering well over 200, showing recent art almost entirely, and there is no shortage of contemporary work to be seen.

The old LACMA, on the other hand, was a rarity. With nearly 149,000 global objects still in a permanent collection that starts in ancient cultures like China’s Eastern Zhou dynasty and Olmec-era Mexico, LACMA is the premier encyclopedic art collection in Los Angeles. In fact, it’s the only one. Indeed, it’s the only one not just in Southern California but in all of the western United States.

LACMA didn’t always do the encyclopedic thing well. That approach should not be romanticized. But neither should we idealize its recent track record with modern and contemporary art, which is certainly no better. It’s just newer and now-er.

It might even be said to be worse, given the cramped narrowness today driving the entire institution. LACMA might be a de facto museum of contemporary art, but frankly it’s not a very good one.

Within weeks, the County Board of Supervisors is expected to vote on releasing $117.5 million in taxpayer funds to help build a much-needed new home for the imposing permanent collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

LACMA razed its permanent collection galleries three years ago, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was taking off, to prepare for a replacement building at a cost of $750 million — and probably more. While the lavish David Geffen Galleries, designed to be a tourism magnet, are now under construction on Wilshire Boulevard, all but a few hundred works are in temporary deep storage. The great Pavilion for Japanese Art is also shuttered. With limited art options, the construction has thrown the program problem into high relief.

The single-story Resnick Pavilion and the three-story Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) remain open, together providing roughly 100,000 square feet of gallery space. (For comparison, the Geffen will have 110,000 square feet.) Given the impressive reserves of LACMA’s collections, the current galleries could have been programmed in countless ways.

Recently I dropped by in search of some paintings and sculptures made prior to the mid-19th century. Nothing in particular, just something, anything, that dated from before then — good, bad or indifferent. An ancient Southeast Asian Buddha Shakyamuni, perhaps, or a Dutch Baroque still life.

How did my search go? Not well. Among well over 700 works, I found 14 paintings and sculptures made before the modern era.

Fourteen.

All are in “Afro-Atlantic Histories,” a middling loan exhibition about Black lives in the diverse visual cultures produced since the 17th century in places where the gruesome slave trade from Africa flourished, especially Brazil. The 14 historical paintings and sculptures are dispersed among nearly 100 modern works. More than a third of those date from the 21st century. Despite the “Histories” title, it’s largely a contemporary art show.

“Afro-Atlantic Histories,” has been radically downsized at LACMA. Plus: In praise of Paul Mescal’s acting and why “Tár” is bad for classical music.

Since my initial search, three more pre-Modern paintings have gone on view. They’re among four dozen paintings and prints — the rest from the 20th century — by Japanese artists in “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing.” The theme is intercultural dialogue that shaped abstract work by the late Los Angeles painter from the 1950s to the 1970s. It’s a contemporary show, with nothing much to say about historical engagements.

So, at the largest art museum west of Kansas City, Mo., we’re up to 17 historical paintings and sculptures on view. The best description for that is: pitiful.

To be fair, two modest decorative arts installations did feature historical objects. One, closing Sunday, pairs 14 contemporary ceramics with 14 historical clay pots and jars from ancient Greece, Rococo France and elsewhere. The other — and by far the more compelling of the two — was a pandemic-postponed survey of exquisite lacquer chests, bowls, platters and vessels from Japan, Korea, China and the Ryūkyū kingdom (Okinawa, Japan). Roughly 80 works in “The Five Directions: Lacquer Through East Asia,” many from the 16th and 17th centuries, were drawn from LACMA’s impressive collection. It closed May 14.

Even here, though, the museum could not leave well enough alone. The show’s theme was how artistic development in a cultural center draws on other traditions from the cardinal directions — north, south, east and west — in historical lacquer works. Thematic groups were arranged around a pedestal hosting a glamorous circular box inlaid with luminous mother of pearl. Titled “Budding of Recollection,” it was made in 2018 by Sano Keisuke, a then-24-year-old student jeweler and craftsman.

The historical collection survey had no real need for the borrowed contemporary piece, a pretty but unexceptional example of a flashy sort available at high-end shops. The box is far less significant or appealing than the many rarities in the show, losing luster by comparison. Its inflated position as the singular exhibition centerpiece reduced it to a token, rather than elucidating profundity in a culture’s continuing tradition.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The shows of lacquerware, pottery and Sam Francis are all keyed to LACMA’s collection. So is “Light, Space, Surface: Art From Southern California,” a very lovely if uninspired new installation of perceptually oriented abstract painting and sculpture, starting in the 1960s. The show’s 20 examples are about half of the 38 that LACMA recently sent on tour to two small museums in the East. That seems a somewhat more coherent show, which underwrote a scholarly catalog and some conservation work. But the current version, a thumbnail sketch devoid of such historically critical artists as Doug Wheeler and Bruce Nauman, feels like filler.

And on it goes, including a just-opened show of 75 recent works, a majority from the collection, by women in Islamic societies. Art’s history is given a nod, but that’s about it. Adding insult to injury, the modern and contemporary shows have been mostly weak.

I made a list of what I thought were excellent exhibitions among the 72 in the last five years; not just good or OK, but excellent. My list has 12 — five modern or contemporary, including solo surveys of artists Barbara Kruger, Julie Mehretu and Charles White. The other two were an overview of modern Korean art, historically fascinating even if it included little truly significant painting or sculpture, plus the wild spiritual abstractions of New Mexico’s inventive Transcendental Painting Group (still on view, until June 19).

Of the seven standout historical shows, one was an unprecedented retrospective of 16th century Ming Dynasty painter Qiu Ying, whose hugely popular blue-and-green landscapes made him China’s most-copied artist. (Unfortunately, it was only on view briefly before the pandemic necessitated closure.) Another was a groundbreaking reevaluation of 16th century Italian woodcuts, an unexpectedly exciting survey of how an early reproduction medium embedded an idea of enlightenment into Renaissance thought and beyond.

Newly opened at LACMA, ‘Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing’ means to show the profound impact that Japanese art, traditional and contemporary, had on the development of Francis’ abstract sensibility as a painter.

A few ratios, however, are telling. The seven noteworthy historical shows were among a total of just 12 presented since 2018. The five standouts of art from our own time were among 60. The other 55 were either routine, the kind of thing you could find all over L.A., or else poor. They weren’t museum-worthy, a distinction now all but lost.

Which is not to say unsuccessful as a magnet for people and for money.

Contemporary art is where the big money and the blazing social spotlight are now, the art market having exploded following the drastic economic crash of 2007-08. The Great Recession altered art culture as surely as the Great Depression had seven decades before it, albeit in very different ways that we’re just beginning to understand.

The pool of available older art had shrunk from earlier buying sprees, while the global proliferation of empty art museums with galleries that need filling continues to grow. Recent art answered the call. Brisk sales turned it into an asset class for investors, something it had never been before, further cementing attention.

Social media, popular among a younger audience, spreads the word in vivid ways impossible before its equally explosive invention. Facebook had 100 million users in 2008 and 2.3 billion just 10 years later. Instagram took off in 2010, TikTok in 2016.

Vast quantities of money sloshing around always grab museum eyeballs — both for the ticket office and among tax-conscious donors. The ever-widening wealth gap in our New Gilded Age expanded and consolidated power among plutocrats.

‘Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group’ at LACMA presents an overdue survey of the abstract painting movement started in New Mexico.

Museum trustee Eli Broad, the late multibillionaire collector of contemporary art, gave LACMA its biggest shove in the direction of highlighting today’s art. As part of his campaign to assert Los Angeles as the nation’s leading center for it, he bankrolled construction of the eponymous BCAM. (Geffen, another multibillionaire, is also a contemporary art collector.) Broad was instrumental in hiring Michael Govan, then 42, as director. An aspiring artist, not an art historian, Govan famously left art school to become a museum administrator, including with the Guggenheim Bilbao. From the directorship of New York’s Dia Foundation, a small operation with a major collection of art made since 1960, he moved west.

In addition to his LACMA duties, Govan has been an active trustee at foundations supporting two of his favorite living artists — Michael Heizer, whose controversial outdoor rock-sculpture “Levitated Mass” fills the Resnick’s entire backyard, and James Turrell, whose retrospective Govan co-curated at LACMA a decade ago. Turrell’s huge “Roden Crater,” which turns a dormant Arizona volcano into a sculpture, and Heizer’s enormous mile-long sculpture “City,” recently unveiled in the Nevada desert, find their urban equivalent in an artist-turned-administrator’s mammoth museum-building project.

Construction of the Geffen Galleries is at least a year behind schedule. Opening is now targeted for late 2025. The plan is to install most of 26 core galleries as changing collection theme shows — many apparently with a contemporary art hook. The lopsided exhibition program of the last decade looks like a disappointing sample of what’s coming full time.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.