Using augmented reality and novel-like storytelling, L.A. designers want to upend the board game

- Share via

Class warfare. The spread of disinformation through social media. A lifelong love affair, and the ways in which passion and grief shape and color our hobbies. These are grand themes, some of-the-moment and others timeless, but all told through the medium of play courtesy of two separate groups of local designers. Both have roots in disparate strands of the world of immersive entertainment — theme parks, alternate reality games, escape rooms — and the format each has chosen to experiment with is decidedly old-fashioned: the tabletop game.

But the companies behind them — Animal Repair Shop’s Infinite Rabbit Holes and Hatch Escapes — have ambitious visions for how storytelling, play and puzzles can intersect. There are familiar entry points — the Batman franchise for Infinite Rabbit Holes and the romantic life of “Frankenstein” author Mary Shelley for Hatch Escapes — but both take different approaches to center narrative rather than simply use story as a setting.

In its “The Arkham Asylum Files: Panic in Gotham City,” Pasadena’s Infinite Rabbit Holes employs augmented reality technology to overlay live-action and animated scenes over a board and various peripheries. It’s a risk, considering that outside of “Pokémon Go,” AR has largely failed to capture the imagination of the public, but the firm makes the argument that AR needn’t simply be used to bring digital accoutrements into our world; instead when it comes to storytelling, AR works best when it is accentuating a confined and defined universe.

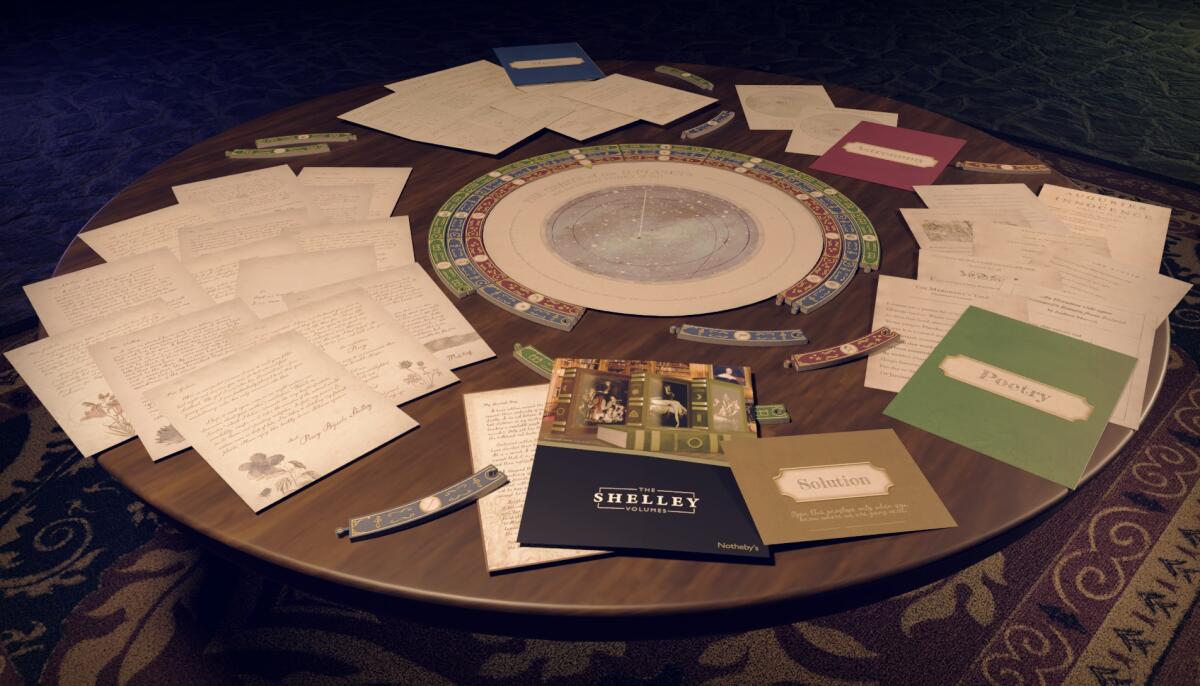

Los Angeles’ Hatch Escapes, home to the lighthearted, comedy-focused escape room Lab Rat as well as the Scout Expedition-created exploratory, live-action game “The Nest,” opts for a more timeless approach. Think of its “Mother of Frankenstein” as part novel, part puzzle game, one in which challenges are sprung from various aspects of Shelley’s life and interests. Open the first of three box sets for the multi-part game and one will be greeted with poems from the likes of William Blake and John Donne, among others, as “Mother of Frankenstein” makes the bet that the home tabletop game can be an expansive work of historical fiction.

Broadly speaking, both titles fit into the category of at-home games that use some escape room mechanics, a genre popularized by the likes of L.A.’s the Wild Optimists, creators of the “Escape Room in a Box” brand. Today, there are multiple competitors in the space releasing an assortment of mystery or true crime games, and one can find home escape games licensed to brands such as “Star Wars” and “Lord of the Rings,” among many others, but the home escape description doesn’t quite summarize what “The Arkham Asylum Files” and “Mother of Frankenstein” hope to achieve. That is: Can a home game outside of the role-playing genre be as good at storytelling as it is at making puzzles?

“Why is there a story with puzzles? Why are there puzzles? That’s already hard. It’s hard to make puzzles make sense,” says Tommy Wallach, co-founder of Hatch Escapes and co-creator of “Mother of Frankenstein” with Terry Pettigrew-Rolapp. “It’s really hard to make puzzles diegetic. It’s almost always a testing conceit. So the question is, why logically are you being tested? The problem there is, even when you go with a testing conceit, it’s antithetical to emotion. Emotionally, people don’t test each other, and certainly not with tricky intellectual puzzles. It’s just not what normal human beings do.”

It’s probably not what Mary Shelley would have done, either. In the game, the author left a series of personal love letters and puzzles for her son, Percy Florence. Each is designed to further reveal details about her relationship with her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, or to her art, and to deliver a message to her son — and the player — that she was too ashamed to reveal while alive. The puzzles are challenging. One is constructed solely out of poems and fictionalized personal letters, asking the player (reader?) to carefully comb the contents to discover the order in which they belong. Another early puzzle explores the music Mary and Percy could have shared, all while turning musical notes into a code that needs to be cracked.

It’s best explored like a novel, in game sessions of an hour or two over an extended period. Both “Mother of Frankenstein” and “The Arkham Asylum Files” can be played solo, but are recommended for small groups. The challenge — and the priority, says Wallach — was attempting to ensure the puzzles remained connected to the story. Sometimes that meant knowingly stressing the player, such as in the second volume of “Mother of Frankenstein” when participants are asked to get a glimpse into Shelley’s research journey (the first two editions retail for $39.99 and the third, which contains a large jigsaw puzzle, for $49.99; expect each to take about five hours).

“Does the gameplay always match the story? That was really hard, and that’s why it took three years. We didn’t nail it 100%. But I would say 80% of the puzzles are gesturally analogous to exactly what’s going on in the story,” Wallach says. Hatch Escapes fictionalized Shelley’s research process for “Frankenstein,” having her in the game study under a scientist to learn about anatomy and galvanism. This allowed, however, for creation of an small research journal that serves as a puzzle container.

“We spent many, many, many months attempting to make this process of her learning about anatomy and electricity effectively feel the way a scientific study feels — that the action of solving the puzzles is repetitive,” Wallach says. “We’ve had people genuinely complain that it’s repetitive, and we’re like, ‘Yeah, we know. That’s what scientific inquiry is like. You get a little farther each time and it’s iterative. And it’s a struggle, and it’s work.’ We want it to feel more like work than your average puzzle. That’s what we were most excited about in doing a puzzle-story game — trying to find that way to bring them together in a way they haven’t been brought together before.”

Much in “The Arkham Asylum Files” will feel as if it hasn’t been seen before. Expect to play most of the game standing, moving a required iOS device such as an iPhone or an iPad around the board — and sometimes around the room. At times, completing puzzles will spring animated scenes to life on our smartphone or tablet, as the game feels like one piece of a larger animated-meets-live action film. We’ll watch, for instance, as escaped digital animals from the Gotham City Zoo run amok over hot dog stands or turn elevated train tracks into jungle gyms.

A later, more elaborate puzzle has players trying to uncover the code to a safe. I scanned cardboard gears with my iPhone, and then tried to correctly place them on a virtual vault that had materialized in my apartment. Elsewhere, I donned the included mask — either Batman or Joker — affixed with a red lens to obscure certain markings on a newspaper. At times we’ll scan ink blots to advance the story via animated scenes in a bright, watercolor-like style. There’s a fluid mix of old and new technology; a maze-like jigsaw puzzle that we construct will need to be scanned via our device to trigger the advancement of the narrative.

It’s a testament to “The Arkham Asylum Files” that I often felt like I was constructing a story more than I was solving a puzzle box. There are times we will pause the narrative to, say, build a 3-D city, but once we erect a cardboard tower representing a Gotham City news station, we can scan the building to watch newscasts materialize on a mini Jumbotron, or solve puzzles via the ever-shifting graffiti on the urban buildings. There are some tech hiccups — for more digital-leaning puzzles I had to reset the whole challenge rather than engaging in the more standard trial and error that a paper and a pen allow — but I ultimately forgave that. The game and its components, both animated and physical — some puzzles are hidden in carnival tickets or cookie boxes — created the sensation of hunting for narrative bits.

“The Arkham Asylum Files” is the rare board game, for instance, that had a script table read in a story that features Batman villain Anarky, among others, in an Occupy Wall Street-inspired narrative. Many an AR app has faltered, largely because the novelty of placing digital characters in our world wears off quickly. “The Arkham Asylum Files” instead creates its own world that the AR can enhance.

“We made a conscious decision to focus on the things that were most reliable,” says Alex Lieu, chief creative officer of Animal Repair Shop. Lieu, like many on the team, comes from Disney, where he worked on interactive initiatives. And Lieu, like a number of Animal Repair Shop staffers, was a part of the group that made the popular alternate reality Batman game “Why So Serious?,” an elaborate marketing tie-in for the 2008 film “The Dark Knight.”

“We created a giant box of things that we have control of, so we know that when we scan it, it works,” Lieu says. “We can’t control everything in the room. But it’s a lot harder for us to map your dining room table and that chair against the wall and be consistent. We can build the format of these documents and the board game and be consistent. It makes it more reliable, and it’s magical. Because we’re putting magic on top of real stuff.”

“The Arkham Asylum Files” is pitched as the first of a three-part story, and the $150 box should create about six to eight hours of story. For Susan Bonds, CEO of the company, it represents a lifelong journey of finding ways to get participants to get out of their own head.

Bonds was previously with Walt Disney Imagineering, the company’s arm devoted to theme park experiences, where she worked on Disneyland’s Indiana Jones Adventure as well as projects at Florida’s Epcot, among others. “I left Disney Imagineering and went into gaming, and it’s fascinating how people in fully digital worlds interact,” Bonds says, adding that through play, we are better able to act at different, sometimes more relaxed versions of ourselves, “There’s anonymity in digital spaces. It’s like, you know me, but you don’t know me.”

“The Arkham Asylum Files” is ultimately designed as a family experience. “We never try to overtax the player,” says Michael Borys, senior vice president of interaction design. “It’s not us against them and us trying to prove how smart we are. We want them to get to the end of the story because otherwise what’s the sense of having a beautiful story?”

But in “Mother of Frankenstein” and “The Arkham Asylum Files” there were moments in which I felt in conversation with the characters. Our group during “Mother of Frankenstein” pored through fictional letters discussing and debating Shelley’s perceived musical tastes and what that meant, and in “The Arkham Asylum Files” we are made to feel as if we’re doing detective work alongside reformed villain Harley Quinn rather than simply retracing her steps.

If there’s a commonality between the two, it’s that both are elaborately written. The amount of text in “Mother of Frankenstein” is equivalent to a novella, and “The Arkham Asylum Files” is built around a script and detailed animated and live-action sequences. “How do you tell a real story? And the truth is, you do it with text,” says Wallach, noting that popular tabletop games are often built on a premise rather than a narrative. “There aren’t words on the page. There’s not enough time to get to know the characters and what they care about. We realized if we want to do this, we’re going to need a huge amount of text.”

Both, too, are evidence that play belongs as much to storytellers as it does puzzle crafters.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.