You could say Elizabeth Alexander was raised among monuments. Growing up in Washington, D.C., she was surrounded by them. When she was a toddler, her parents took her to the March on Washington in 1963, where hundreds of thousands of protesters brought ebullient life to the steps of the temple-like Lincoln Memorial. When she was a girl, someone told her that the obelisk-shaped Washington Monument was actually “God’s pencil.” As a student, she took field trips to the various memorials whose designs were inspired by Classical architecture. Of these structures, she says she grew to understand “something about their scale and awe.”

She also came to realize everything monuments could distort and elide.

In the capital, where the breadth of the nation’s history is presumably honored, in a city that in the early 1970s was largely populated by Black people, any depiction of them was exceedingly rare. Most prominent was the Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park, unveiled in 1876, which shows a slave laborer kneeling at the foot of Abraham Lincoln, who wields the Emancipation Proclamation in one hand.

Shouldn’t public monuments have public input? In the George Floyd moment, artists and designers are changing the nature of monuments and the histories they honor.

The sculpture has long been criticized for the ways it whitewashes the role played by Black activists in bringing an end to slavery. Alexander, who grew up near Lincoln Park, where she’d often walk with her mother, says she felt the figure looked abject. “He doesn’t look free,” she says. “It’s the kneeling supplicant with the great white savior.”

Which is why she also clearly remembers the moment when that monument received a counter. In 1974, the National Council of Negro Women installed a sculpture in honor of educator and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune across the plaza from Lincoln (which was rotated to face her). It was the first monument to honor an African American and a woman on public land in D.C.

Monuments remain a critical part of Alexander’s polymathic life.

A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 2006 for her collection “American Sublime,” monuments have materialized in her verses:

Growing up in Washington,

I rode D.C. Transit, knew Senators,

believed the Washington Monument

was God’s pencil because my friend Jennifer said so.

She has also scrutinized their meanings. In her 2022 essay collection, “The Trayvon Generation,” Alexander analyzes the racist roots of the Confederate Memorial Carving at Stone Mountain in Georgia — and notes that monuments are never simply a thing of the past. “Monuments put forth ideas and look forward, even when their content is historical,” she writes. “They chart future value by what they revere.”

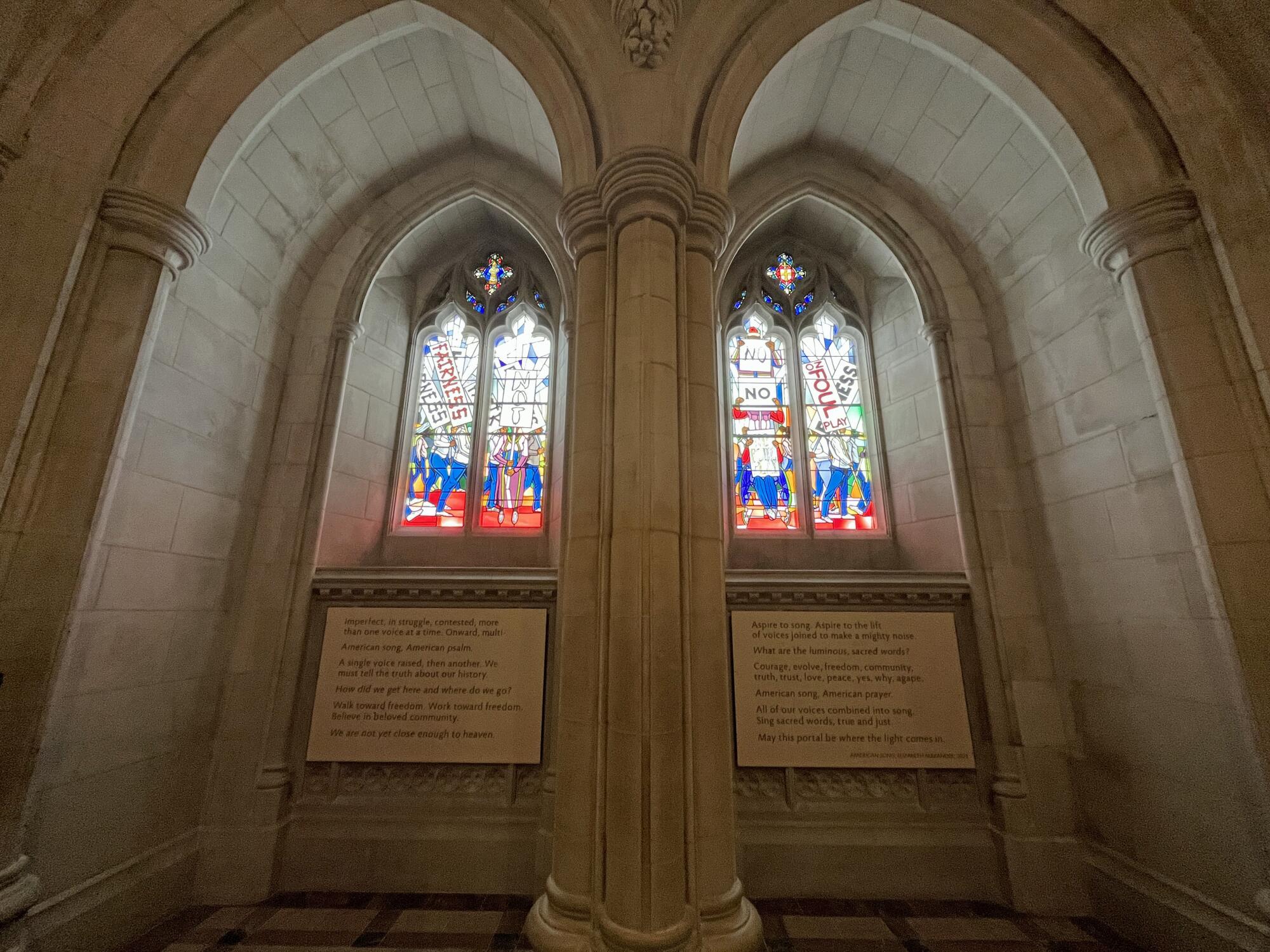

Alexander’s work even appears in a monument. In September, the Washington National Cathedral inaugurated a pair of stained glass windows designed by artist Kerry James Marshall that depicts peaceful protest. Adjacent to the windows is Alexander’s poem “American Song”: “A single voice raised, then another. We / must tell the truth about our history.”

But it is in her post as president of the Mellon Foundation, a position she has held since 2018, where she has had her greatest influence. Alexander has helped put the weight of this powerful New York City foundation behind initiatives to study, preserve and recontextualize monuments — as well as remove them when their communities no longer deem them appropriate. In November, Mellon announced it would commit $250 million to its Monuments Project — on top of the $250 million it had already put toward this effort when Alexander launched it in 2020.

The project is incredibly ambitious, a national effort to make sure that the commemorative landscape “more accurately tells our collective histories.” It has led to shifts — big and small — in how public places are presented and what is even considered a monument. In Idaho, a $1.5 million grant from Mellon is supporting the physical preservation of El Milagro, a labor camp built by the Farm Security Administration in 1939 that housed migrant workers from around the U.S. and the world. In New Jersey, the foundation contributed $350,000 toward the creation of a monument to honor abolitionist Harriet Tubman, installed last spring. In Kansas, it helped fund the relocation of a 28-ton boulder that was sacred to the Kaw Nation to parkland owned by the Kaw.

Alexander says monuments are a critical part of the civic landscape. For one, they are public — their forms and their messages absorbed by anyone who happens across them. “You’re saying this is a focal point,” she says. “This is where we meditate, where we worship, where we are.”

And where we are reflects a stunning lack of diversity — not simply in terms of gender or race but in the histories that monuments honor and the forms that they take. (So much marble and bronze.) In 2021, Monument Lab, a Philadelphia nonprofit that studies monuments (and has received funding from the Mellon Foundation), published its “National Monument Audit,” which analyzed almost 500,000 monument records across the country.

New stained glass by Marshall in honor of peaceful protest — along with a poem by Elizabeth Alexander — replace a 1950s tribute to Confederate generals

It found that monuments to war outnumbered those to other causes and those to white men likewise outnumbered everyone else. Among the top 50 individuals honored in public monuments were Confederate leaders including Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general who was the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Junípero Serra, the controversial Franciscan friar who established the mission system in California, also was on the list.

Monument Lab’s researchers found that there were more recorded monuments to mermaids (22) than to U.S. congresswomen (2). “The story of the United States as told by our current monuments misrepresents our history,” concluded the report.

Alexander notes that Mellon doesn’t decide which monuments to preserve or which to take down. “We don’t go to places and say, ‘Time to reckon,’” she explains. “We look for places where they are reckoning and we try to support what they are trying to do.”

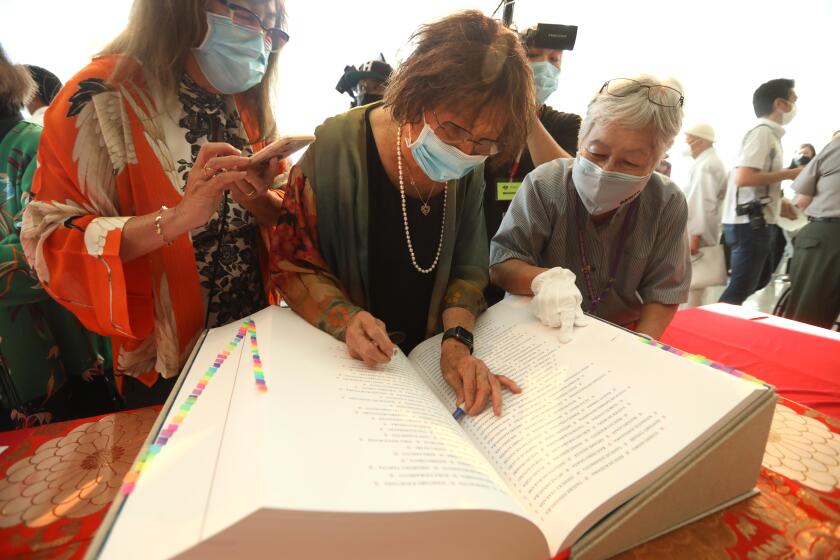

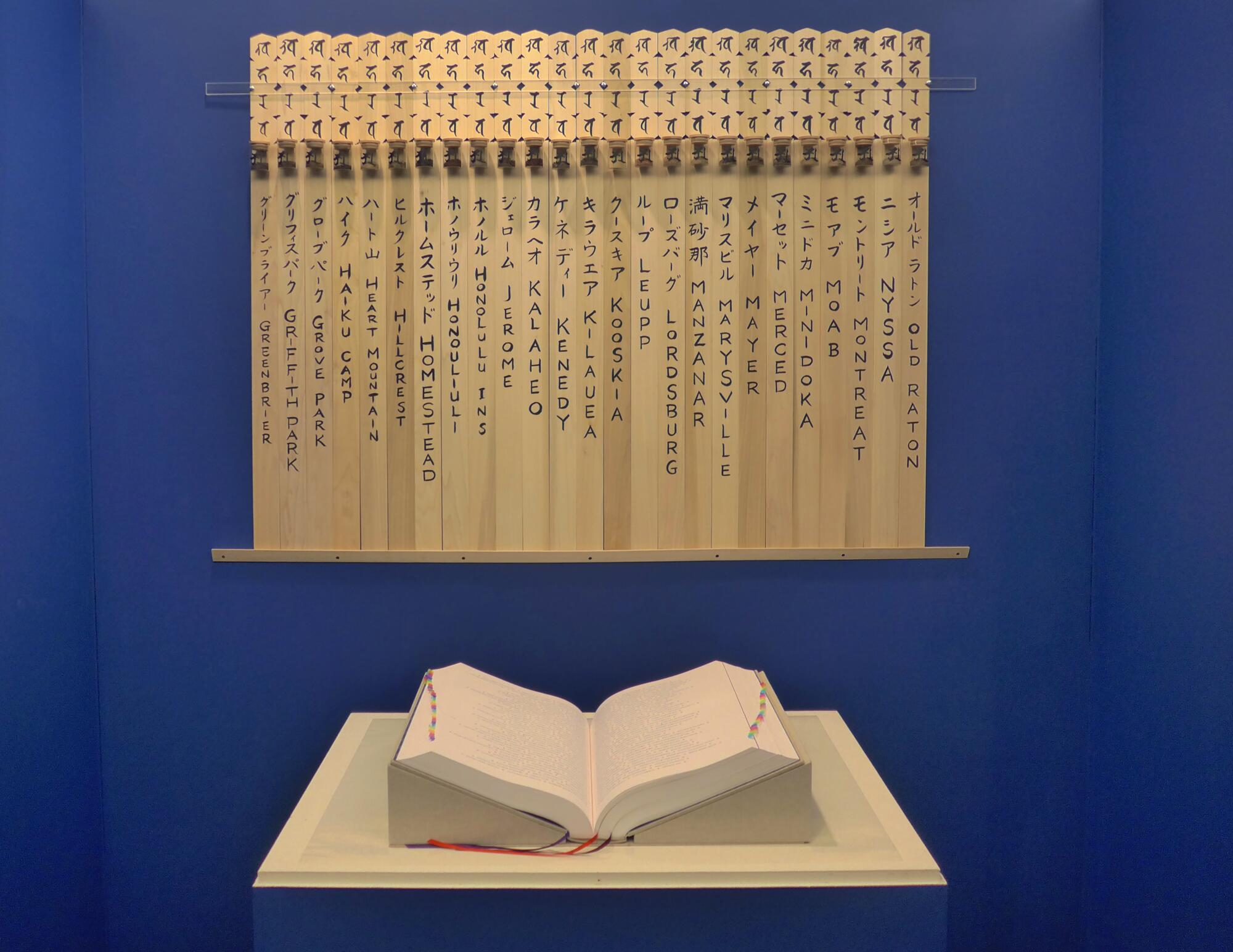

This has included supporting projects that don’t always fit the classic (Western) definition of a monument. At the Japanese American National Museum in downtown L.A., for example, Mellon has supported a project called Ireichō, led by USC professor Duncan Ryūken Williams, that centers on a book. It weighs 25 pounds and contains the names of the more than 125,000 Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II. Visitors can make an appointment to stamp the book as a gesture of acknowledgment.

“There are so many ways we mark spaces to tell stories,” says Alexander. “This monument is a book.”

One of the more intriguing projects has been the relocation of the boulder sacred to the Kaw, an Indigenous tribe that once inhabited Kansas but is now headquartered in Oklahoma. The Sacred Red Rock (Iⁿ‘zhúje‘waxóbe in the Kanza language) is a red quartzite boulder that once sat at the confluence of the Kansas River and the Shunganunga Creek east of Topeka.

In 1929, however, city leaders in Lawrence, Kan., relocated the monolith to a park in Lawrence as a way of commemorating the city’s 75th anniversary. To add insult to injury, they affixed a plaque to its surface to honor the city’s white founders. There was no mention of the Kaw, who had been forcibly removed from the area in the 19th century.

In the next year, survivors and their descendants will make a pilgrimage to the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo to stamp the names of their loved ones.

In January 2020 — months before monuments had become a hot-button issue in the wake of George Floyd’s death — a group that included Kaw leaders, artists and historians began to conduct research and hold community workshops about the Sacred Red Rock. This led to a demand by the Kaw that the rock be returned. In 2021, a Lawrence commission approved the request, and a $5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation helped relocate it last summer to Allegawaho Memorial Heritage Park, a Kaw-owned site southwest of Topeka.

“We have been separated from our grandfather for more than 150 years,” said Jim Pepper Henry, vice chair of the Kaw Nation, upon the occasion, “and we look forward to being reacquainted.”

Alexander says the project has been an important one — since it not only reconsiders the nature of monuments, it is a way of surfacing a history that had been overwritten. “Folks hold on to the stories of their people no matter what,” she says. Part of her aim with the Monuments Project is to help make those stories more visible.

On a blustery January afternoon, I catch up with Alexander at the Watts Towers, where conservators from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art are working on securing pieces of the towers’ elaborate façades. In 2019, Mellon contributed $500,000 toward conservation of Simon Rodia’s legendary complex — a DIY art project that has since become an icon of Watts and, more generally, of Los Angeles.

Rosie Lee Hooks, director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, says that to some people in the community, the towers are more important than the Statue of Liberty. “It wasn’t floated in,” she says. “It was built by an immigrant over a period of 33 years. It’s in the community, it’s a part of the community and the community is very involved.”

For Alexander, the towers represent an opportunity to support a monument that was built organically from the ground up rather than installed in top-down fashion. They also represent something more personal.

Two reports — by the city of L.A. and Monument Lab — reveal blind spots in how California marks its history. A memorial to the Chinese Massacre sets a new agenda.

The daughter of the first Black secretary of the Army and a historian who taught at George Washington University, Alexander is a writer and scholar whose academic stints include running the Boutelle-Day Poetry Center at Smith College and the African American studies department at Yale University. Her work, regardless of the silo she’s working in, often straddles an array of themes — social, political and artistic.

Her poems have examined the imagined lives of Black historical figures, and her 2004 collection, “The Black Interior,” brought together powerful essays on Black domesticity and what it means for Black people to witness episodes of violence against them. In 2009, she wrote and recited a poem — “Praise Song for the Day” — at President Barack Obama’s inauguration. Seven years later she was once again a Pulitzer finalist (in biography) for her book “The Light of the World: A Memoir,” a lyrical meditation on the untimely death of her husband, Ficre Ghebreyesus, an artist and chef.

In 2015, she left academia to work at the Ford Foundation, helping shape that organization’s grant-making efforts in the area of art and culture. Three years later, Mellon invited her to interview for the position of president. The idea for the Monuments Project was generated over the course of those interviews.

Alexander’s interest in monuments is certainly intellectual and political, inspired by the notion of “caretaking the history and spirit of a place” and giving voice to groups whose stories have been erased or overlooked. In addition, the looming possibility of another Trump presidency — he has described Confederate monuments as “beautiful” — has given the Monuments Project an added urgency. “We are working with burning intensity,” she says.

But her interest in the subject is also drawn from her lifelong interest in art, and the way a great work can move us in surprising, confounding ways.

Alexander made her first pilgrimage to the Watts Towers in the late 1980s, before she had completed graduate school, after learning that the site was an important source of inspiration to celebrated L.A. assemblage artist Betye Saar. “Betye Saar’s work has been so important to me,” says Alexander. “The work felt like poems. She has such an understanding of the power imbued in objects.”

Writer tapped to read at inauguration was taken as a tot to hear King’s ‘Dream’ speech.

Alexander finds similar power in Rodia’s towers, which are embedded with bits of tile, broken dishes and even corn cobs — “things that have previous lives and they carry spirit and memory, and are about people making something out of that which has been discarded.” Things, ultimately, that carry stories that aren’t part of the official record.

The towers appear in a poem Alexander wrote titled “Stravinsky in L.A.,” which was published in her 1996 collection, “Body of Life”:

The Watts Towers aim to split

the sky into chroma, spires tiled with rubble

nothing less than aspiration.

With her work at Mellon, she hopes to make that aspiration stand for several more generations. “I can’t believe that it’s my job,” she says. “I can help preserve this sacred space.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.