Column: 1984 Olympic Arts Festival all but reinvented L.A. Why the 2028 Games could do the same

The Paris Olympic Games are beginning. Or so NBC and the media would like you to believe. In fact, between early June and now, Paris and other parts of France have already presented about 1,000 events in the 2024 Olympiad. The Cultural Olympiad, that is. The host city of every Summer Olympics holds an arts festival, just as Los Angeles did 40 years ago in such spectacular fashion that it dramatically changed our city not only culturally but physically, economically and, maybe more important of all, psychologically.

When it comes to the way L.A. looks, acts and thinks about itself, you can credit some of that to the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival.

Our arts festival was nothing like what is happening in Paris. The City of Light is, of course, the city of art, and its Cultural Olympiad reflects Parisians-being-Parisians on steroids. Living up to the transforming vision of Marcel Duchamp, everyone is an artist, and everything is art.

From the Cultural Olympiad maps, it appears that you can barely walk a block without witnessing some related arts project, be it at a museum, department store, theater, cafe or public square. Along with concerts and opera and all the highbrow rest, the Louvre is offering special exercise classes in galleries. Cafe waiters are staging races, trays in hand. DJs are taking over public spaces. The public was invited to propose projects. There is something for everyone.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Was it like that in ancient Greece? From 776 BC to 393 AD, the ancient games included the involvement of philosophers, scholars, artists and politicians alongside the athletes. But it took a Frenchman, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, to invent the modern Cultural Olympiad, beginning with the 1912 Games. Along with the contests of sport, he mounted five parallel contests in architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture. In 1913, the good baron memorialized that in his design of the five Olympic Rings.

The 2024 Paris Olympics start this week, and 594 athletes will be competing for the United States. Here’s how you can watch and stream any of 329 events.

After World War II, the Cultural Olympiad became a summer arts festival in which the host city celebrated and showed off its culture. In 1968, Mexico City held an extravagant year-long festival that combined modern art with folklore. More than 8,000 events were staged in the 2012 London Cultural Olympiad, attracting some 170,000 people. A phenomenal staging of Stockhausen’s monumental opera “Mittwoch” in Birmingham included a string quartet performing in four helicopters buzzing overhead. The assistant director happened to be Yuval Sharon, who had just founded avant-garde opera company the Industry, and who, empowered by the sheer audacity of “Mittwoch,” would go on to stage “Hopscotch” in vehicles cruising downtown L.A.

All of this, of course, should be of newly pressing interest to Angelenos. None too soon, the city has announced that Maria Arena Bell, a former board chair of the Museum of Contemporary Art, will be leader of the LA28 Cultural Olympiad. As much fun as a Cultural Olympiad sounds, with luck our arts officials will carefully consider what our Olympic Arts Festival in L.A. accomplished instead.

The Olympic Arts Festival was just that, intentionally breaking with tradition and avoiding the Olympiad moniker. Our major arts institutions, including the then-new MOCA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Music Center and the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center, along with various dance and theater companies, participated in 400 events. But the real intention and the bulk of the $11-million budget went toward bringing great work from Europe and Asia to L.A. (and, in some key cases, to the U.S.) for the first time. It was a festival meant less to glorify ourselves than to show us who and what we could be. It was a revelation.

The festival was the brainchild of Robert Fitzpatrick, a restlessly domineering visionary and brilliant fundraiser who was president of CalArts. He had the patronage of City Hall and particularly Mayor Tom Bradley. But he fiercely demanded and got uncompromising artistic independence.

Sparing little expense, Fitzpatrick opened the festival with the U.S. debut of Pina Bausch and her Dance Theater from Wuppertal, Germany. The first night featured her “The Rite of Spring,” in which Bausch required dancers to dance, on a stage shockingly covered in soil, as though they were about to die. It was a gala event with Olympic and civic dignitaries in the audience. Like the rest of us, they were blown away. We simply had no idea.

That was the festival. We simply had no idea when near-naked Sankai Juku dancers covered in white ash performed a “hanging dance,” as they were lowered down by their ankles from the roof of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in what has been described as sublimated eroticism.

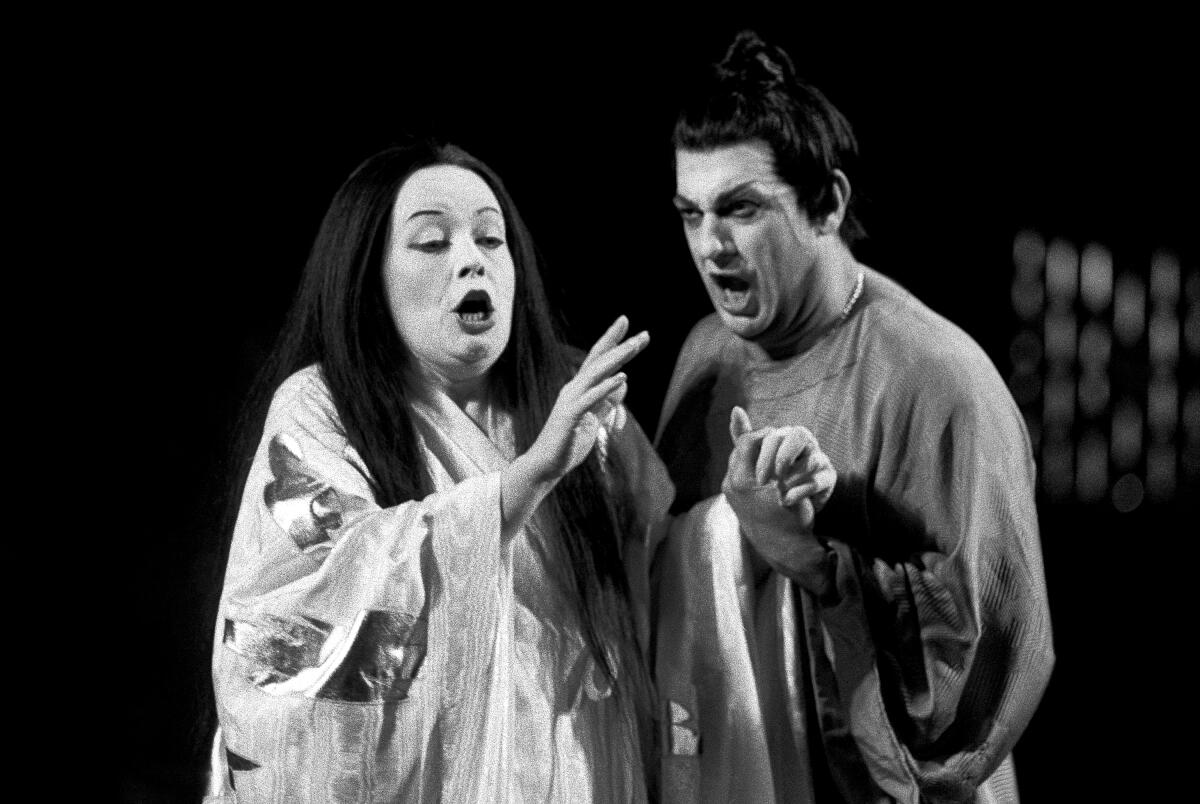

The same could be said of the U.S. debut of Le Théâtre du Soleil, which combined Japanese kabuki, Indian kathakali and Italian commedia dell’arte traditions in French-language Shakespeare productions. Or the great Italian opera director Giorgio Strehler’s magical production of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” with his Piccolo Teatro di Milano. Clowns from Brazil one night, the Australian Circus Oz from Melbourne another, the intense Polish theater company Cricot 2 performing on a television soundstage another, and on and on.

London’s Royal Opera brought three big, full productions — “The Magic Flute,” “Peter Grimes” and “Turandot” starring Placido Domingo — to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The response was so enthusiastic that, after a century of failed attempts to create a major opera company in Los Angeles, Music Center Opera (now Los Angeles Opera) was born.

The L.A. Phil’s lasting gift to the Olympics was a concert at the Hollywood Bowl conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas. It opened with John Williams’ “Olympic Fanfare,” commissioned for the occasion. Hear it — as we repeatedly will over the next few weeks — and the world instantly thinks Olympics.

The Olympic Arts Festival’s incomparable, if indirect, gift to the L.A. Phil was Walt Disney Concert Hall. The festival so transformed how Angelenos felt about their city that suddenly grand projects seemed feasible. After Music Center Opera triumphantly opened its first season in 1986, L.A. Phil Executive Director Ernest Fleischmann, hardly eager to share the Dorothy Chander Pavilion, went to Lillian Disney with a proposal to fund a concert hall. Thanks to the Olympic Arts Festival, Fleischmann easily had the backing of City Hall and county supervisors.

Museum exhibitions may not have been as important, but here too, the range was extraordinary. LACMA had a blockbuster French Impressionist landscape exhibition. “The Black Olympians, 1904-1984” was at what is now the California African American Museum. JACCC showed rare treasures from the Kasuga Shrine. I was keen on the International Festival of Masks at Pan Pacific Park.

You couldn’t not notice the festival, given that 10 artists were commissioned to create freeway murals. Everything, everywhere, drew large crowds. Ticket prices mostly began at $10 or less and topped out at $30. Opera was more, but even then some seats were $15.

Nothing, however, came close in ambition to Robert Wilson’s “the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down,” a 12-hour opera commission that was to be mounted in the Shrine Auditorium the first week of the festival.

The project comprised five full-scale sections created in six countries with a vast cast of singers and actors, including the incomparable soprano Jessye Norman and David Bowie. Philip Glass led a list of composers that included David Byrne, Gavin Bryars, Nicolas Economou and Jo Kondo. Wilson looked at the civil, racial and social wars of our time and the world’s reaction with vividly ambiguous theatrical imagery.

The individual sections, as well as the Knee Plays, or connecting sections, were variously workshopped or produced in Cologne, Rome, Rotterdam, Marseille, Tokyo and Minneapolis. But funding fell short to bring them to America. When it came down to the wire, $1.2 million was needed. Much of the arts festival had been funded by a handful of L.A. philanthropists, but no one stepped forward.

The L.A. Phil Hollywood Bowl season opens with rising conductor Elim Chan conducting Prokofiev’s Second Violin Concerto with Agustin Hadelich and ‘Scheherazade.’

The international art world looked on aghast. Wilson was an international star. Had “CIVIL warS” been scheduled for the end of the festival, not the beginning, the money would have been easily found, donors by then having understood the importance. Yet the lesson of this failure demonstrated the essential need to make this, like no other Olympic festival, permanent.

Fitzpatrick proposed a triennial Los Angeles festival. In 1997, he did it again by introducing the U.S. to Peter Brook’s epic “Mahabharata” performed on a Hollywood soundstage and by organizing Cirque du Soleil‘s American debut and a large-scale celebration of John Cage’s 70th birthday. Fitzpatrick was too successful; Disney poached him to head the new Paris Disneyland.

One criticism Fitzpatrick faced was his showy projects tended to be European. His L.A. festival successor, opera director Peter Sellars, addressed those issues directly, by mounting revolutionary festivals in 1990 and 1993.

In 1990 Sellars focused on Pacific Rim cultures, especially reflecting our large Asian communities. Who knew, for instance, that a star of traditional Chinese opera might be a refugee working in a Monterey Park cleaners? Sellars presented theater and music and exhibitions and film all over town with local performers along with major figures from Pacific Rim countries. Nearly everything was free, be it Indian raga or an all-night outdoor Balinese puppet play.

For his second festival, Sellars turned to African American and Latino communities, addressing the racial and economic issues tearing L.A. apart. Those economic issues also were personal. Festival funding had been dramatically cut.

Although Sellars’ festival got considerable attention from the press in New York, London and elsewhere, recognizing L.A. as a multicultural world leader, L.A. itself wasn’t ready for this. Without local institutional or media support (this paper included), the festival turned out to be ahead of its time and couldn’t continue.

We’re far more culturally confident and sophisticated than we were in 1984, before the Getty Center and the Broad museum, before Disney Hall, before the L.A. Phil became the king of the orchestras, before L.A. Opera, before so much else. We have become a far more important arts capital.

But do we have an LA28 “CIVIL warS” in us any longer? Can we still find the great art hidden in our many backyards? Can we count on civic and City Hall support these days? Can we not understand that, as 1984 so powerfully proved, thinking big in the arts can uniquely give the city the courage and willpower to think big about all of our essential issues, beginning with the housing crisis?

The Games’ excitement will come and go. But living up to 1984 will require LA28 to open minds wide enough to change lives.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.