Norton Simon (1907-1993) was a hard-nosed industrialist whose Depression-era turnaround of a bankrupt Fullerton bottling plant ultimately grew into the sprawling Hunt‘s food empire. (Ketchup, anyone?) As Southern California flourished, so did his bank account. Along the way, Simon built the most impressive private art collection in America to be assembled after World War II.

The avid collector flirted with several institutions to become permanent home to his staggering holdings, but finally he couldn’t let go. By the time he was strategizing a contentious, ultimately successful takeover of the financially faltering Pasadena Art Museum in 1974, his collection numbered some 12,000 works.

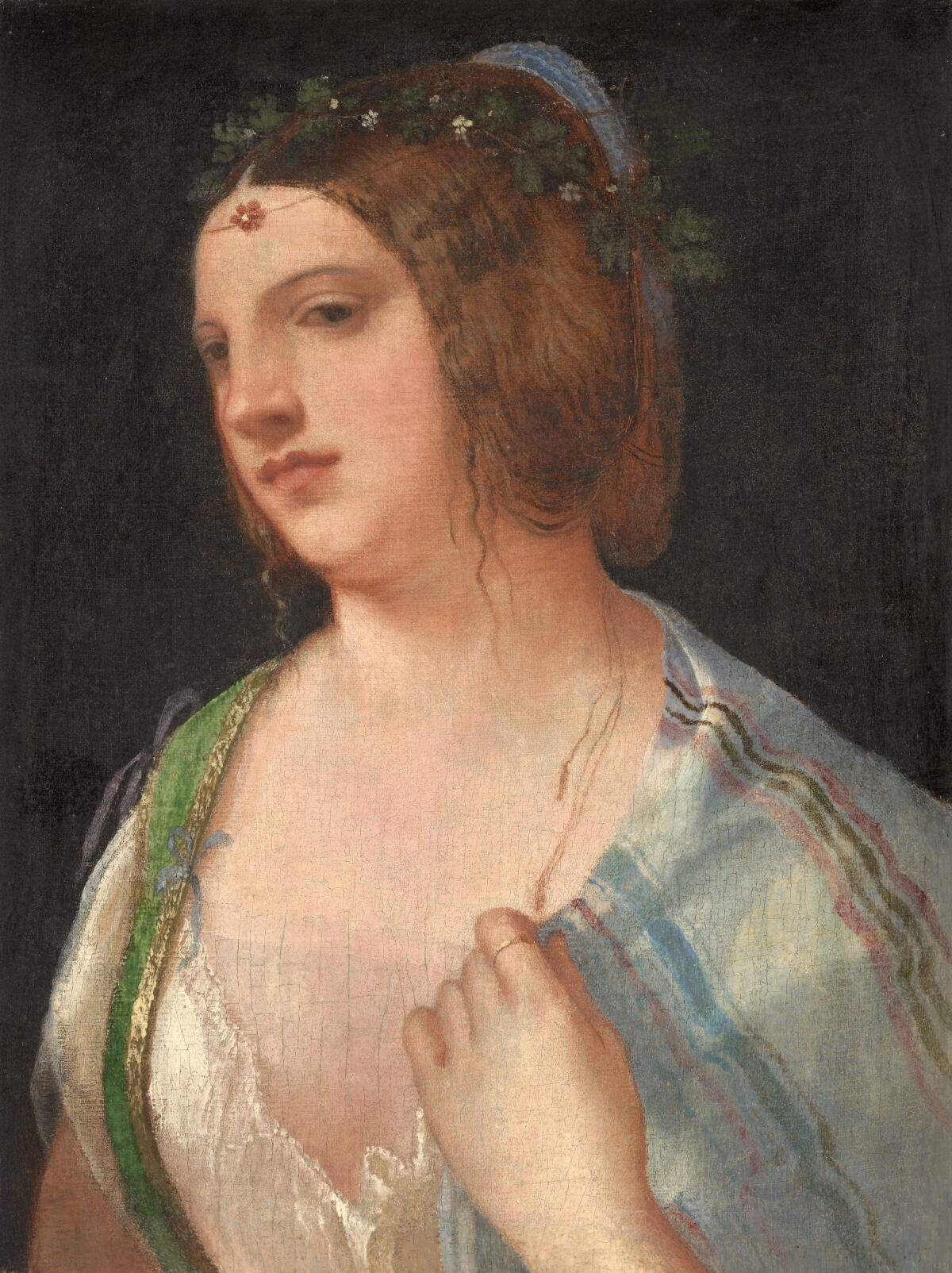

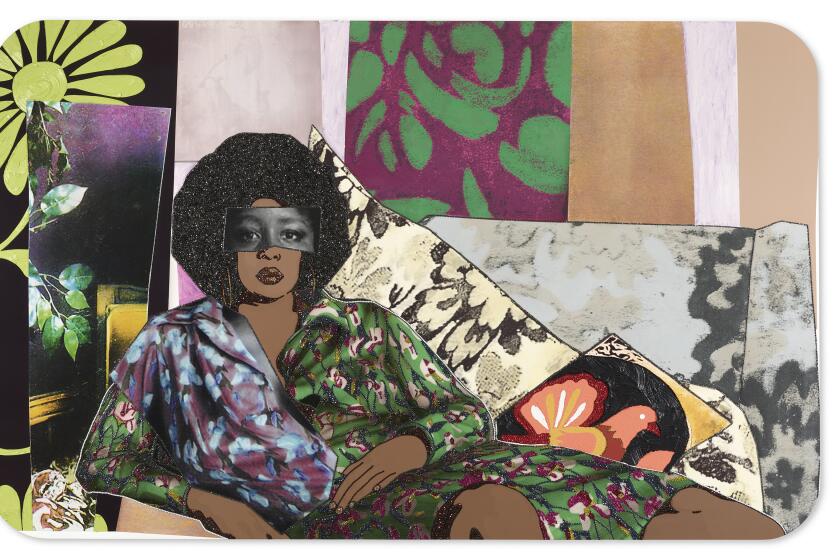

Today, one long arm of the museum building’s unusual floor plan, shaped like the letter H (and handsomely renovated by architect Frank O. Gehry), features an exceptional array of European and Old Master paintings and sculptures. The other long arm holds impressive 19th century and Modern art. Downstairs, in rooms that open onto a garden — a rather noisy one, given the roaring Ventura and Foothill freeways adjacent — are striking displays of Indian and Southeast Asian art.

The only real museum shortcoming is an entrenched habit of exhibiting almost every painting behind glass, which can yield a one-step-removed look to even the most commanding picture. (What I wouldn’t give to see unencumbered the otherworldly radiance of the humble “Still Life With Lemons, Oranges and a Rose,” the museum’s signature 1633 masterpiece by Seville’s Francisco de Zurbarán.) Still, the sustained level of quality throughout is unmistakable. That defies what follows from being a “best of” list, but it has been selected to give a sense of the broad range of notable art on offer.