‘The Good Place’ creator Mike Schur on the pressure to find the perfect finale

As the creator of “The Good Place,” Michael Schur has spent years honing the art of brain teasers on morality and mortality. That may explain why death creeps into some of his thoughts on television.

It comes up when he’s talking about the paralyzing volume of TV: “We’re all going to die with thousands of hours of unwatched television on our DVRs.”

Or in trying to crystallize the fear of missing out that’s piqued by really good TV: “I met [‘Breaking Bad’ creator] Vince Gilligan for the first time between that show’s split final season. And I told him a true fact: When I was 24 and [“Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace”] was about to come out, I had a thought all the time, which was, ‘Please don’t die, just please don’t die.’ Because it would be so sad if I got hit by car in May of 1999 and the last thought that went through my head was like, ‘I don’t know what happens.’ ... And I had that feeling again in the time between the last two ‘Breaking Bad’ seasons. It’s the most potent feeling a consumer of entertainment can have: ‘Please don’t die before this comes out.’ ... I had it most palpably with ‘Breaking Bad.’ But I had it with ‘Lost’; I definitely had it with ‘The Sopranos.’ I have it retroactively when I think about the ‘Cheers’ finale. You feel sadness and remorse and fear, but also you’re thrilled and it’s just such a rare thing.”

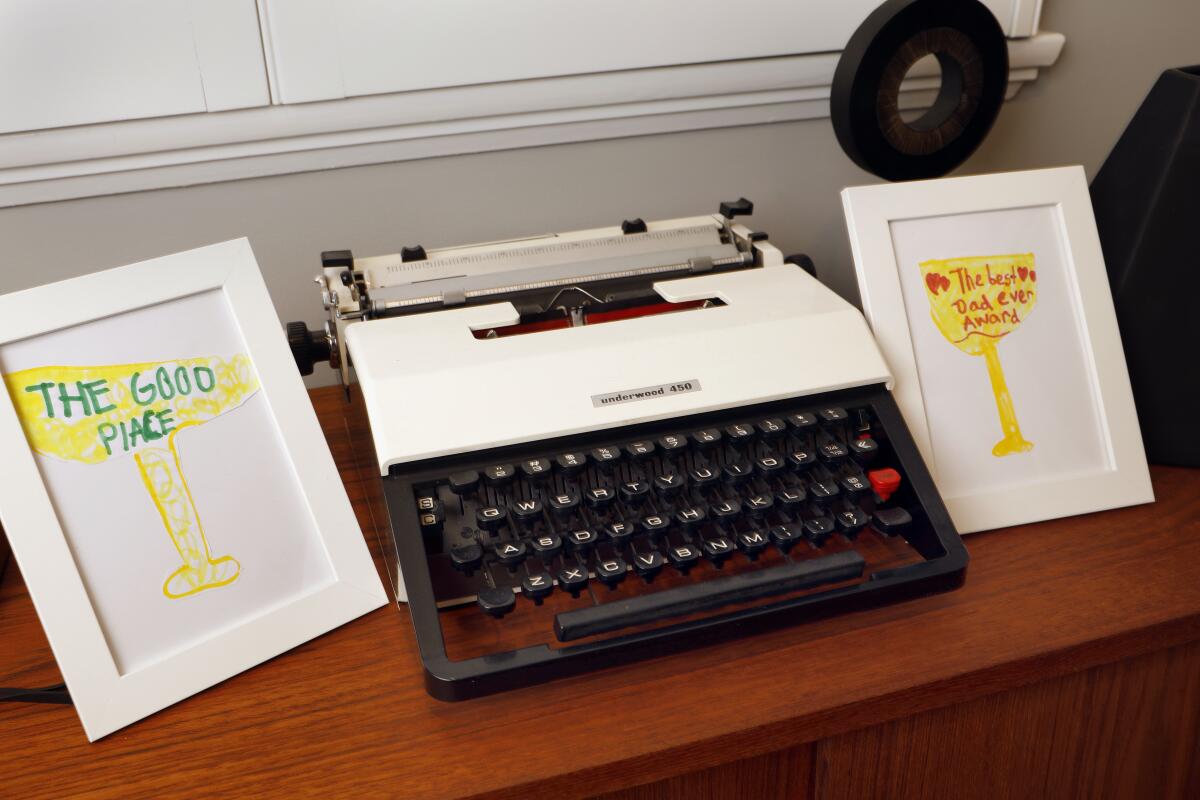

That’s just some of what came up in conversation earlier this month at Schur’s bungalow office on the Universal backlot — a short walk from the stages that housed “The Good Place” during its four-season run. The Emmy-nominated afterlife comedy embarks on its final season Thursday, bringing one of TV’s most unpredictable sitcoms to a close.

“The Good Place” is the third series Schur, 43, has created. Since cutting his teeth as a writer on “Saturday Night Live” in the late ’90s/early ’00s and, later, working on the U.S. version of “The Office,” Schur has become one of scripted TV comedy’s most prolific creators, with shows like “Parks and Recreation,” “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” (which he co-created with Dan Goor) and “The Good Place.” He also serves as an executive producer on shows such as Netflix’s “Master of None” and NBC’s new Kal Penn-led comedy “Sunnyside.” And his empire is only growing. Schur recently renewed his overall deal with Universal Television — at a hefty price — just as many of his counterparts have fled for the deep pockets of streaming services.

Surrounded by framed posters of his TV imprint, Schur talked about aiming for satisfaction — not perfection — with a series finale, putting narrative before longevity, and the value he still finds in working with a traditional TV studio.

‘The only superlative it’s going to be is the last’

I think when we were writing the “Parks and Rec” finale, it felt like people were obsessed with finales in a way that I think is unhealthy. ... “The Sopranos” finale and the “Mad Men” finale, the “Breaking Bad” finale and the “Lost” finale — people wanted those shows’ finales to be the best episode of anything that had ever happened. And it’s just asking too much. For example, I think the best episode of “Breaking Bad” was the one that was third from the end. It was the one that started with the shootout in the desert, and it was just one of the most riveting hours of television I’ve ever seen. I loved the finale too. I really did. I liked it a lot, but there were some people who reacted to it like, “How dare you not be as good as the one that happened two episodes ago.” Right? And so that just seems like you’re putting too much pressure on that thing.

And so when we were writing the “Parks and Rec” finale and breaking the story, I was like, I can’t make this the best episode of the show. It’s impossible. There’s too much to do and it has to have a different tone and a different feeling. And so the word that I kept coming back to was “satisfied.” I just want people to feel satisfied. Like, it’s not going to be the funniest episode ever. That one probably aired in Season 4 or something. It’s probably not going to be the most emotionally fulfilling in some way, because that’s probably when Leslie and Ben got married. So it’s very hard to make it any kind of superlative. The only superlative it’s going to be is the last, right? So I just wanted people to feel like they had been on a journey for 124 episodes and that at the end they felt like we did a good job in telling you how it all ends. Right?

So, that was the goal for “The Good Place,” except this has a slightly different element, which is it’s incredibly plot-driven. So it has this gigantic overarching plot, but when we started breaking the episodes this year, we had a similar discussion in the writers’ room that was basically like, “We can’t save everything for the last episode.” There’s just not enough time. It’d have to be a three-hour movie.

‘Nothing that you learned, you learned in vain’

A lot of the early discussion about Season 4 was like, “What are the loose threads that are out there? What have we gestured at and never followed through on?” In order for the final season of the show to feel satisfying, it has to feel like nothing that you learned, you learned in vain.

Unless it’s “The Sopranos,” which the whole point in “The Sopranos” was dangling threads. That episode where they’re chasing the Russian through the woods, or the snowy woods, and they shoot him and then he just runs off and people speculate for years of, “When are we going to see that guy again?” Because that’s how you’re trained as a viewer, and David Chase’s answer was, “You’re never going to see that guy again. That’s not the way the world works.” Things aren’t neat and tidy. You don’t get wrapped up. But our show is different. The characters have been on a very specific journey within a very specific system and they’ve had a very specific goal for how to revamp that system and we can’t get to the end and go, like, “Well, who knows what happens next?” Like, you just can’t do that. So, we did spend a lot of time thinking about, “What are the things that we’ve done in previous seasons that seem meaningful, even if at the time they weren’t intended to feel that meaningful? ... Which of those can we bring back? Which of those can have a sort of impact on the end game?”

‘I hope Ted’s there’

The most fun part of this, I think, is basically designing a very ad hoc college course in moral philosophy and getting people to teach it to me for free. I actually had that thought early on while I was writing the pilot, or very early in Season 1: “What am I going for here?” in terms of the way that philosophy is used in the show. And I had the thought of, “If college level professors think enough of this show to use it as a teaching aid, then we will have done our job.” That was sort of a goal. Because what that means is, we have distilled it down to something that’s basically right. We’re not screwing up. We’re not ascribing beliefs or thoughts to people who didn’t express them. We didn’t get it wrong and we’ve made it entertaining enough that a professor would think to herself or himself, “Oh, this can help me actually explain this complicated thing.”

One of the ways that I sold this show early on to people was, “Look, let’s put it this way. If you died and you woke up on a couch and Ted Danson opened a door and said, ‘Come on in,’ you’d be happy. You would be like, ‘Oh, everything’s fine. Ted Danson’s here and I’m fine.’” That was why he’s perfect for the role of a demon pretending to be an angel. But also, and this is a thing we talk about in the last season, we talk about conceptions of death and the afterlife and what different people thought at different times. Everybody’s just guessing. I hope I’m right, though. I hope Ted’s there.

‘The idea can dictate the length of the show’

It used to be that everybody had the same goal, which was make as much money as you can, as fast as you can. I mean, it’s not that you can’t make money that way. Of course, studios are always looking for “The Big Bang Theory” and “Modern Family.” Why wouldn’t they be? But you don’t have to. There’s other ways that they can make TV shows and make money on them.

You can now make a good living, and the studio can profit from your good living, when you make the exact idea that you want to make, exactly the way you want to make it, with exactly the number of episodes you think it merits. The idea can dictate the length of the show. It can dictate the number of episodes per season. It can dictate the number of seasons you do ... and it makes everyone’s life better because we didn’t have to do three seasons of this show where we just frantically ran in place and threw stuff against a wall and hoped that people didn’t get sick of us. We did exactly what we wanted to do in exactly the amount of time we wanted to do it in. Show creators don’t have to serve a sort of “one size fits all” model of commerce, and the companies don’t have to demand it from their showrunners.

‘There isn’t a factory big enough’

Universal TV has been very good about going to outside places and trying to sell shows. At some point it’s possible that those places are going to close their doors and say, “We don’t need your shows,” because they don’t want to pay a premium to outside studios. I hope that doesn’t happen soon but it seems like, at least for now, all of these places need content from everywhere. There isn’t a factory big enough to supply every one of these places internally. Even Disney, the biggest media company in the universe, they can’t make everything that they need.

The other thing to say is that, in my opinion, there are a lot of shows that are on streaming services that would be better if they were on network TV. And, yes, network TV can be annoying. You have to make every episode the same length. You have commercials, and there’s a bunch of gak on the screen — you’re in the middle of a scene where Chidi and Eleanor are talking about something emotional, and then like something will pop up saying “‘Chicago Fire’ tonight at 10 p.m.” or whatever. That’s annoying. There’s a lot of annoying things about it. However, I think a lot of streaming shows would be better off if they were five minutes shorter. I think a lot of comedy gets flabby on streaming services. I think obstacles are good for comedy. I think being forced to hone everything down to its barest essence makes things sharper and funnier and crisper.

I think the stuff I make is better because I have to jam it into a tiny box. I may be wrong. I mean, we release longer cuts. There are certainly many episodes of stuff I’ve worked on that I think are best at 23½ minutes instead of 21½ minutes. So be it. I’d rather have it be a little bit shorter and not optimal than way too long and not optimal.

‘It’s a very insidious practice’

I’m on the [WGA] Negotiating Committee. The only regret I have is that I didn’t care more about all this stuff sooner. It’s not that you don’t have to worry about it. You do. It’s just that you don’t understand it. I knew what it was vaguely, but it’s a very insidious practice, right? Because when you’re a staff writer or a story editor, and you get a job and you find out you don’t have to pay your agent commission because there’s something called packaging, your reaction is, like, “Sweet.” There’s no part of you that thinks about the long-term effects on the business. Or what it means for you in terms of the way that your agent might be or might not be fighting for your salary or whatever. I obviously have thought more and more about it as I was in the business longer. Then switching from being a staff writer, to a co-[executive producer], to an EP, to creator, or whatever.

Like any great corporate masterstroke of screwing over labor, the process is insidious. Because it makes you feel like you’re winning a prize and really it’s the opposite of that. Being aware of what’s happening is always a good idea. But it’s just not one of the top 10 things on your mind. Another reason it’s such an insidious practice is [agencies] knew full well no one’s going to care about this. This is a side deal. They made a side deal with the studios and the side deal had this active benefit for their clients, which was they didn’t have to pay commission. Everybody wins. It’s just they win way more than you do. Right? When you’re 24 and you get your first staff job or whatever, the last thing in the world that you want to think about is the long-term ramifications on the labor market. It’s a little bit unfair to ask anyone to think about that. Because what you’re thinking about is, “Can I afford my rent? Can I afford food and clothing and shelter? Can I fly home to see my parents at Thanksgiving?” That extra money that you’re not paying in commission helps you. You’re not thinking about this kind of calcified system where the people who represent you are actually making more money by dealing with the people that they’re supposed to be yelling at on your behalf. I don’t blame anyone for not having cared about it until now. But now we all should care about it.

This story is part of the ongoing series Running the Show, in which The Times speaks with showrunners of your favorite TV programs about breaking into Hollywood, writers’ room secrets, being the boss and more challenges of the job.

TV

Running the Show

Yvonne Villarreal’s interviews with TV creators and showrunners

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.