‘Law & Order’ is back, and it hasn’t changed. That’s exactly why it’s lasted so long

- Share via

Back after a 12-year interregnum is “Law & Order,” the Coca-Cola Classic of NBC’s Dick Wolf universe. It’s not as if the brand, or its sister brand of shows that begin with the word “Chicago,” has been moribund in the meantime, with its hot-button topics, its where-and-when title cards, accompanied by a signature dun-dun. Still, it is nice in a way to have back a “Law & Order” that builds its episodes around homicides rather than, like “Law & Order: SVU,” sex crimes — even though the opening episode in the long-in-coming 21st season does involve sex crimes. And you will find that, except in the manner the series was always changing, swapping new characters in and out over its many years, the taste remains the same.

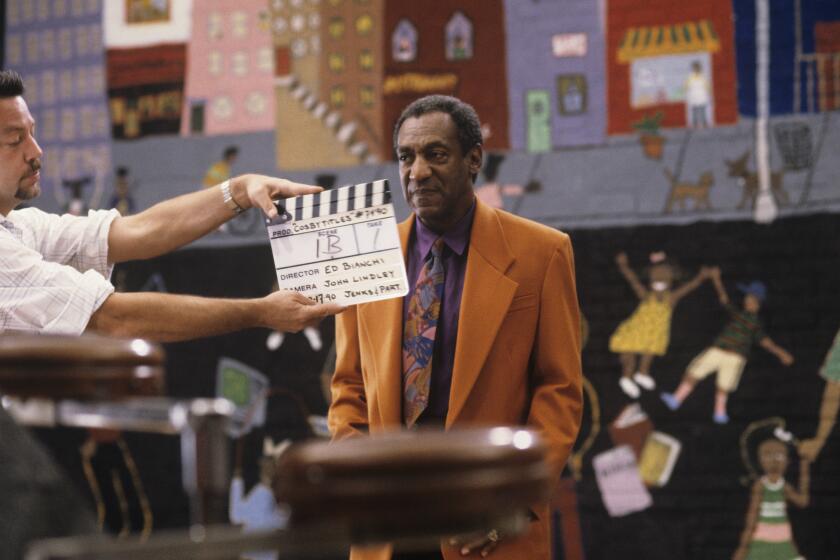

With the show’s usual slightly-behind-the-curve topicality, the season’s first victim is … not Bill Cosby, of whom you are absolutely meant to think, the traditional “the following story is fictional, etc.” disclaimer at the top of the show notwithstanding. (“Law & Order” takes its stories from the news, but rearranges the words and changes the names.) Here, the victim is a musician, convicted of rape, then sprung from prison on account of a prosecutor’s misstep. (That prosecutor is played by guest star Carey Lowell, a “Law & Order” regular back in the 1990s.)

A new doc details the history behind the landmark sitcom and its disgraced creator. And that thorny legacy has implications beyond ‘The Cosby Show.’

Bridging the temporal gap are Sam Waterston, back as Jack McCoy, now the New York district attorney, and Anthony Anderson as Det. Kevin Bernard, newly partnered with Jeffrey Donovan’s Frank Cosgrove in the NYPD’s Ripped From the Headlines Division. Bernard, who is calm, courtly and considered (“Every victim deserves respect, even the ones that raped 40 women”) and Cosgrove, a bit of a hothead (“I speak my mind, probably about things I shouldn’t speak my mind about, but it’s just how I’m wired”), are still taking each other’s measure; they will have occasion to dialectically examine issues of police practices, community and race relations and so on. (Of all “Law & Order” series, the original is also the one least interested in the personal lives of its characters.) They report to Camryn Manheim’s Lt. Kate Dixon, in the position most notably and lengthily occupied by S. Epatha Mekerson (now a regular, as a different character, in Wolf’s “Chicago Med”).

Their search for the killer will lead the detectives at high speed through a familiar variety of social strata and authentic New York locations — brevity being the soul of “Law & Order,” owing to the fact that their investigation must be concluded in half an hour. (As in “Dragnet,” in which Sgt. Joe Friday was constantly instructing garrulous witnesses to stick to “just the facts.”) Indeed, the first half of “Law & Order” — which really should be called “Order & Law” for chronological accuracy — is a system to deliver the accused to the prosecutors, whose business will take up the second half. Other “Law & Order” series mix prosecutors into the police procedural, but only the original gives us one and then the other, if with a little bit of bleed. (It is not a completely original idea: the 1963 “Arrest and Trial,” with Ben Gazzara and Chuck Connors, was similarly constructed, though they had a more generous 90 minutes, with fewer commercial breaks, to get it done.)

At the 50-yard line the show is passed to assistant district attorneys Nolan Price (Hugh Dancy) and Samantha Maroun (Odelya Halevi), with Waterston’s DA appearing in doorways to offer comment, advice and philosophy, and to remind his assistant DAs— who have their own differences of opinion and approach — that “the big bad police department are our partners, and in case you haven’t been paying attention they’re under attack… There are people trying to defund them, for God’s sake.” He will ask questions not easy to answer, as on the subject of lying to a suspect to extract a confession: “Where do we draw the line…. One lies, two lies? … Do white lies count? Do we examine how charming a detective is? … What if a cop says we have five witnesses instead of four, do we throw it out?” Well, it makes you think.

The courtroom scenes, with its no-nonsense judge, fired-up defense attorney, unexpected witness and tactical turnarounds, all in the “Law & Order” tradition, will keep the prosecutors breathing hard until the denouement. As with every legal procedural ever, the viewer may find himself objecting when a lawyer doesn’t.

Although an occasional narrative experiment might disrupt the format, what makes “Law & Order” special is precisely the fact that it has one, like a sonnet, a sestina, or an ottava rima. You can dip in anywhere across the years, and whether it’s Jerry Orbach and Benjamin Bratt, Orbach and Jesse L. Martin, or Dennis Farina and Michael Imperioli beating the pavement, or Michael Moriarty and Richard Brooks, Waterston and Jill Hennessy, or Waterston and Angie Harmon trying the cases — or any other variation in personnel through the mix-and-match decades — and get the same effect, the same satisfaction. (Broadly speaking it is a show made up of questions and answers, on the case and in the courtroom.) In its very structural predictability, it wants to reflect the justice system it represents, which might go haywire from time to time — a fact the series actively acknowledges, and which is central to the season opener, the only new episode available for review — but is meant to give you the soothing sense, generally, that things are in good hands.

The series can be issue-oriented almost to a fault; that is, you are quite aware that points are being made as points are being made. (When Lt. Dixon tells Det. Bernard, who has observed that it’s the “first time in 20 years people actually care about a Black man getting shot,” that he can “save his speech for someone else, because I am not in the mood for politics right now,” it’s a kind of feint, since “Law & Order” is never not in the mood for politics.) In the opening episode, there are chanting protesters, bystanders with phones up to record an (almost) heated exchange between a white detective and a Black citizen, followed by a discussion between the detectives on the pros and cons of being photographed. (They will agree, finally, that accountability is good.)

In a guest column for The Times, author and “Law & Order” fan Carmen Maria Machado explains what makes the characters more powerful together than alone.

Historically, the show is a strange mix of the naturalistic and the stylized; its shorthand, no-filler approach gives it a declarative style (leavened by the odd ironic scene-closing remark — another “Dragnet” inheritance) that can feel as much pageant as drama. The characters are not so much people as allegorical figures, representatives of justice, gone well or gone wrong.

In the final shot of the Season 21 premiere, Dancy’s ADA Price, having opined that “if you try a good case, if you do it the right way, whatever the jury decides is right, whether or not it feels good,” looks up at the facade of the New York State Supreme Court Building, a Roman-inspired temple of justice, upon whose pediment we see inscribed “nistration of justice is the firmest pillar of good.”

It fills out to “The true administration of justice is the firmest pillar of good government.” But I had to look that up.

‘Law & Order’

Where: NBC

When: 8 p.m. Thursday

Rating: TV-14-LV (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 14 with advisories for coarse language and violence)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.