Commentary: McCarthyism makes us agents in our own destruction. ‘Fellow Travelers’ shows how

The second episode of “Fellow Travelers,” Ron Nyswaner’s steamy melodrama of queer life in midcentury America, concludes with Langston Hughes’ “Kids Who Die,” a poem to sting the back of your throat. Marcus Gaines (Jelani Alladin), Senate correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier, has already made a connection with Frankie Hines (Noah J. Ricketts), bartender at D.C.’s hottest underground haunt, but it’s this recitation that makes their communion complete — as surely as a kiss might, or a sly wink, or a secret handshake.

Still, it’s another of the poem’s stanzas, unspoken here, that points most forcefully to “Fellow Travelers’” project. The American screen’s finest, frankest ever treatment of the Lavender Scare, the anti-communist purge of LGBTQ+ people from U.S. government in the 1950s, the series bravely acknowledges that McCarthyism, past and present, demands collaboration — that its arsenal is comprised not only of denunciations, fiery speeches and show trials but also of silence, complicity and self-protection. “All kinds of kids will die,” as Hughes had it,

Who don’t believe in lies, and bribes, and contentment

And a lousy peace.

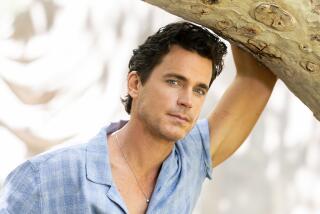

For “Fellow Travelers” protagonists, Hawkins “Hawk” Fuller (Matt Bomer), a suave State Department functionary, and Tim Laughlin (Jonathan Bailey), a bright-eyed Irish Catholic idealist, the lousy peace of the Cold War becomes a personal and professional battleground. With Sen. Joseph McCarthy (Chris Bauer) on a crusade against the capital’s “communists and queers,” the pair’s furious affair demands not only layer upon layer of secrecy but also careful plotting in the halls of power to defuse the attacks. And, as is its wont, survival swiftly turns ruthless: Hawk plants Tim in McCarthy’s office as a reluctant double agent, and hands over the name of a one-night stand to protect a colleague under threat.

Billy Eichner’s tweets are misplaced: The freedom ‘Bros’ extols is the freedom to fight over, criticize and, yes, ignore the art that represents us.

If the series, based on Thomas Mallon’s 2007 novel, has a singular strength, it’s this willingness to frame the Lavender Scare, and other defining moments in queer history, as a form of internecine conflict. When Marcus, who is Black, comes face to face with Frankie in drag, he decides he can’t simultaneously defend his sexual orientation and campaign for racial justice. When Mary Johnson (Erin Neufer), Hawk’s friend and Tim’s beard, finds herself in the vise grip of the anti-communists, she betrays her own partner rather than sacrifice her career. The dots connect all the way up to McCarthy: Long before rough trade in Rehoboth Beach accuses the senator of sodomy, we see Joe — unmarried, close to his mother, notoriously handsy — treat his right-hand man, venomous homosexual Roy Cohn (Will Brill), as if they’re “newlyweds”; look past Cohn’s affection for consultant David Schine (Matt Visser); and leer at Tim as Don Draper or Roger Sterling might their nubile new secretary. As “Fellow Travelers” depicts, and the numerous villains of queer history demonstrate, the call of repression regularly comes from inside the house.

Against the committee-room grandstanding of popular memory, the series thus fashions the entire Eisenhower era from the raw materials of the closet, from subtext, secrets, sidelong glances and confidential tones. Tellingly, it’s not the sex between Bomer and Bailey, exactly, that shivers with erotic force: It’s a prurient reference to kneeling in prayer; the arch of a foot pressed against a man’s chest; Hawk telling an enthralled Tim to “fold them” after he slips off his pants. That their attraction is inextricable from this performance of dominance and submission only underscores the point, for as we learn in flashes forward to the 1980s, it isn’t only a fantasy. Hawk’s power — to pass, to prosper, to marry the right woman (Allison Williams) and hold out for the right post — is brutally, catastrophically real.

Then again, silence, that sharpest of double-edged swords, is not a weapon easily trifled with: What ensures survival in one regime equals death in another. It’s Tim, in the process of discovering his own voice, who soon recognizes in Hawk the unfeeling operator, the self-described “Switzerland,” the “coward,” and so poses the greatest threat to his position. By the time the beautiful naïf delivers a defiant, brassy tribute to Doris Day in Friday’s episode, “Hit Me,” he succeeds, one might say courageously, in ruffling Hawk’s feathers, and by extension our own. As played by Bailey in a career-changing performance, Tim’s yearning — sexual, emotional, spiritual, political — is so palpable, so persuasive, that Hawk’s white-knuckle grip on what is, rather than what could be, reveals itself as a form of weakness. Mere survival is no way to live.

Showtime’s ‘Fellow Travelers’ is both a sweeping romance — with graphic but authentic sex scenes that already have viewers abuzz — and a chronicle of queer history.

Seventy years later, McCarthyism persists, even as its figureheads and foot soldiers have changed over time. It still defines as American a constellation of ideological positions against which all others must be labeled abnormal, and cast out of the body politic as if a contagious disease. It still demands collusion, censures dissent, confuses the exertion of power with the protest against it. What differs — and not by much — are simply the noms de guerre, communism ceding to socialism, subversive to woke. For the target, as “Fellow Travelers” intuits, isn’t queerness, or racial equality, or anti-capitalism per se, but nonconformity of any sort, which power seeks to stamp out for its own preservation. And there will always be people — like McCarthy, Cohn or the fictional Hawkins Fuller — so eager for a slice of power they become agents of destruction, even if the ruin should some day be their own.

In this, “Fellow Travelers” crystallizes the irony at the heart of its title. The term with which McCarthy and his cronies smeared countless Americans who were not and never had been “card-carrying members of the Communist Party” originates with another tongue, and has the opposite connotation. For the failing implied by the Russian poputchik, applied to political sympathizers who refuse to state their support publicly, isn’t guilt by association. It’s lacking the courage to refuse lies, and bribes, and contentment, to reject the lousy peace — whether the issue is the harassment of drag queens and trans people or prejudicial firings in the State Department; the killing of thousands of children in Gaza or the overthrow of democratically elected governments in Guatemala and Iran; Black Lives Matter or the Montgomery bus boycott.

Then and now, McCarthyism thrives where fellow travelers proliferate — not because they defy the status quo, but because they remain silent about it. So speak up.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.