Q&A: Artist Sam Durant was pressured into taking down his ‘Scaffold.’ Why doesn’t he feel censored?

- Share via

The grassy mound at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden now lies empty.

Last month, a controversial sculpture by Los Angeles artist Sam Durant stood on the site. Titled “Scaffold,” it was a representation of seven gallows used in historic U.S. government executions, including those of abolitionist John Brown in 1859, four anarchists in Chicago’s 1886 Haymarket affair, credited as the inspiration for international workers’

Durant’s sculpture had been exhibited previously in Europe three times, but upon landing in Minneapolis for the reopening of the Sculpture Garden, curated and operated by the Walker Art Center, it sparked a media firestorm. Native American activists said it trivialized one of the ghastliest episodes in Dakota indigenous history. Said one Dakota protester to the Minneapolis Star Tribune: “It’s not art to us.”

In early June, following the initial outcry, Durant, who is white, came together with Dakota elders and museum officials and agreed to remove “Scaffold.” He also signed over the intellectual rights to the piece to the Dakota people.

“I have no intention of making a representation of that again,” says Durant. “They asked me, ‘How do we know you won’t do this again?’ I said, ‘That makes perfect sense. It’s yours. You decide what happens to it.’ ”

The artist’s concession has not been without controversy. At least one anti-censorship group described the decision as “hasty” and said that it “set an ominous precedent” that could put a chill on difficult, politically minded work.

Walker executive director Olga Viso, who was quick to address the controversy when it first emerged in late May, disagrees.

“Everyone had agency in this conversation — especially the artist,” she says. “The artist led it and offered it. He does not feel censored.”

Both Viso and Durant say that their decision has to do with a specific local context that may not seem apparent when viewed from elsewhere.

“All of these things have nuances and complexities that need to be taken into consideration,” she says. “We all feel that we moved to a place of mutual respect and consideration. The work still has power. It lives in archives, in oral histories and the actions of people that live on and were part of this.”

In the wake of the incident, Durant sat down with The Times for a lengthy interview (which has been edited and condensed). Seated in a book-filled corner of his Santa Monica studio, looking pensive and, at times, chastened, he explained the ideas that led him to create the piece to begin with — and why he won’t stop exploring issues of inequity and race in his work.

How do you arrive at the idea of making a sculpture inspired by historic gallows?

It’s a very iconic structure. It’s one we know particularly from filmmaking. I had been interested in the John Brown gallows. There is a very bizarre wax museum in Harpers Ferry that has a reproduction of those gallows.

At the time, I was also doing research on labor movements, anarchism and what became known as the Haymarket Martyrs, these German American labor organizers who were working in Chicago [in the 1880s]. There was a big May Day gathering in Chicago, someone threw a bomb. No one could ever prove who threw it. Four were executed. That gallows is very well known in labor history.

Then I found the last public execution, which was in 1936. It was a man named Rainey Bethea, an African American man tried for the rape and murder of an elderly white woman — under very racially charged circumstances. An astounding number of people turned up for that. That was in Kentucky.

In a way, these things to me symbolized certain aspects of American history: class war, genocide of Native Americans, slavery. It looked at the state monopoly on violence, of which the execution is the ultimate symbol.

So, in the work, it was a fairly straightforward representation of these structures. The construction method was to construct the decks one on top of the other. It was all to scale. It was designed so that visitors can climb the staircases and go up on the platform. It was designed in such a way to retain some of that iconic visual presence.

The Dakota people basically saw something that looked like a monument to their massacre....As one person said to me, ‘That's a killing machine.’

— Sam Durant, artist

Why do these episodes in U.S. history hold such interest for you?

I think history is not about the past, it’s about the present. In that context, this country has not dealt with history at all. It’s interesting to compare it to Germany, for instance, where everywhere you go, there are monuments, memorials, markers to the Holocaust. It’s taught. It’s integral to the curriculum. It’s part of the fabric of German society: “Never again.”

The United States needs that kind of situation. So we need to first of all acknowledge the genocide of Native American people and that our country is built on slavery. Our wealth is built on slavery. Until we acknowledge it, it’ll be very hard to progress. As I learned in Minneapolis, we are all still losing and being victimized by this history.

You couldn’t have a better test case of white ignorance in one place.

— Sam Durant, artist

When did you learn that there was an issue with “Scaffold”?

I heard about it the week before Memorial Day weekend. I was [in Los Angeles].

The sculpture was erected in a very prominent part of the garden, so it was highly visible. The garden itself had not been opened, the whole thing was fenced off, but you could see [the piece] clearly from the roads and paths. [Members of] the Dakota community recognized the Mankato gallows in the sculpture. It was very visible in the sculpture. The museum — and I’m sharing the blame — didn’t reach out to the community. We didn’t think of it, to start a dialogue before we started building it. There was no information.

So the Dakota people basically saw something that looked like a monument to their massacre. Mankato is burned into their consciousness. It’s not abstract. As one person said to me, “That’s a killing machine.” Then it turns out that the garden is located on [historic] Dakota land. So you couldn’t have a better test case of white ignorance in one place.

The museum called me and said there might be protests. And they said, “People might want to take the work down, and how do you feel about it?” My immediate thought was, “Oh, they don’t understand the work. And once they understand it, they’ll be OK with it.”

But when I got there, I saw a very different perspective.

I think history is not about the past, it’s about the present. In that context, this country has not dealt with history at all.

— Sam Durant, artist

How did that perspective evolve?

Well, things escalated very quickly. A protest developed, and then there was a backlash to the protest. There were people driving by the protests and screaming racist things at [protesters], saying things like, “That’s our trophy, don’t you touch that,” and throwing rocks at them. I thought, if somebody gets hurt because of this — that’s not what my work is about.

The Dakota elders stepped in, and they [ultimately] offered to do a session with a mediator. [The Walker] asked me if I would come. I said I wouldn’t miss it.

What was that session like?

It was a really wonderfully experienced mediator who ran the whole thing. She’d been at Standing Rock and specialized in trauma issues. There was a group from the Walker, the Dakota elders and me. It was a ceremonial circle. From their perspective, it was a spiritual session and not a political one — which allowed for a certain kind of dialogue, maybe a more open and honest one. It was very emotional.

I tried to explain a bit what the work was about. But I felt I should be listening, so that’s what I tried to do. The main issue was how real that structure was for them. That was the main point. The elders were very calm and respectful and thoughtful but also passionate about their view.

First, we talked about removing the Mankato gallows elements and leaving the other six. I did some images of what it would look like. But there was a feeling that a bridge had been crossed. As long as that structure was up, it would continue to remind them of what had been there.

They asked me to take it down, and I agreed.

The National Coalition Against Censorship issued a statement criticizing the dismantling of “Scaffold.” Others in the art world have also been critical. What is your view?

Censorship is when a more powerful group or individual removes speech or images from a less powerful party. That wasn’t the case. The Dakota are certainly not more powerful, in political terms, or in terms of the international art world. I could have said at any point, “No, I want the work to stay up as it is, end of story. Walker, you deal with it.”

But I chose to do what I did freely. For me, it was that the work no longer fulfilled my intentions. I always hope my work would be in support of Native American struggle and justice. To hear that it was harming them, I felt terrible. I had to change it.

I don’t feel that I can’t take up any subject that I want to. The question is how do I do it?

— Sam Durant, artist

When [the mediation session] ended, the mood was good. From my perspective, I was like, “Oh, wow, I just did something that has never been done. And what does this mean? I hope I made the right decision.” I had those kinds of feelings. But as time went on, I know I did the right thing.

You’ve tackled race in your work throughout your career. Have you been criticized before for being a white artist examining these topics?

It comes up all the time. But I’d never had nonwhites bring it up. Usually the question was framed coming from a white art world audience: “You’re white, why do you care about this stuff? It’s not your thing.” My argument has always been that whites created race and racism, we created the situation and use it for our benefit, mostly unknowingly, so it’s up to us to be involved in acknowledging it and dismantling it.

The question of cultural appropriation never came up until now. But this situation [in Minneapolis] has given me a different perspective.

In the ’80s and ’90s, there were a lot of debates in the art world about artists representing suffering bodies. My position had been that I’m not exploiting anybody. I’m not using images of people or bodies. I felt so sure of myself, confident and smug. What I learned in Minnesota is that you don’t have to have images of people or bodies to traumatize. That was a very humbling experience.

I chose to do what I did freely. For me, it was that the work no longer fulfilled my intentions.

— Sam Durant, artist

How did your interest in these topics emerge?

I grew up on the South Shore [in Massachusetts], very close to Plymouth Rock. My elementary school — we would take trips to the Plymouth wax museum. An interesting thing happened when I was quite young. There was a protest on Plymouth Rock on Thanksgiving. It was in the early ’70s. It was the United American Indians of New England. They were saying, “Hey, America, this is a catastrophe for us, not a celebration. It’s a day of mourning.” I remember thinking, “Oh, there’s another side to this.”

That was in the context of a moment of American culture, an education system that was very progressive. We had Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn and radical pedagogues like John Holt [an advocate of home schooling and youth rights].

In my undergraduate studies [at the Massachusetts College of Art] I was in a sculpture program, and my sculpture teacher was very political — very much influenced by labor and the labor movement, very old left. That was sort of encouraged, which isn’t always the case in art colleges or art programs anymore. The norm there was to do work that was explicitly political.

How has this changed what you will do moving forward?

It’s made me much more aware how I will represent issues in my work. I don’t feel that I can’t take up any subject that I want to. The question is how do I do it? What information and what images do I use? Maybe there are some I don’t use?

I’ve started researching Confederate monuments and memorials. I already know that I need to be in touch with the organizations that are involved with this: groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center, the NAACP, groups on the ground. I don’t know yet if I will do that project. But I’m still committed to these kinds of issues.

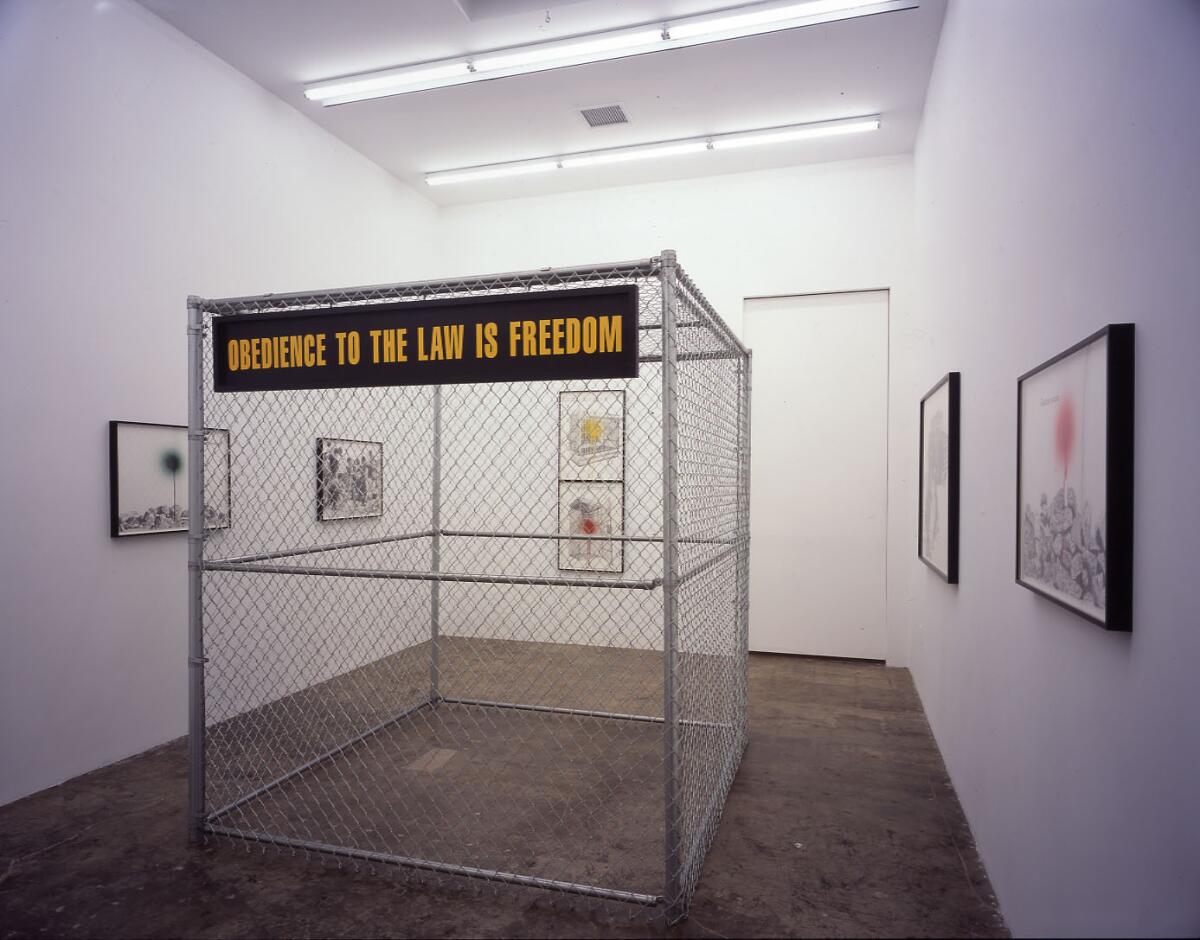

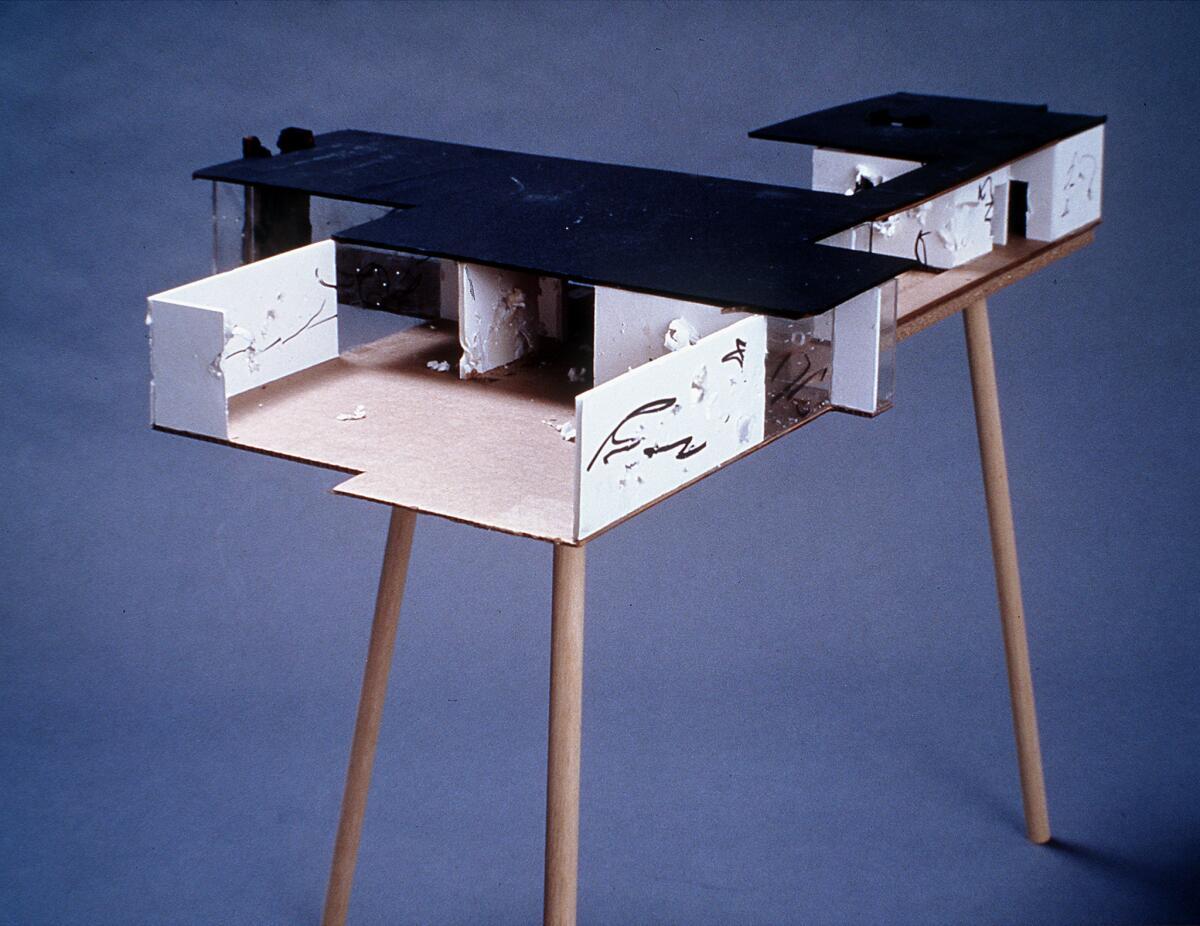

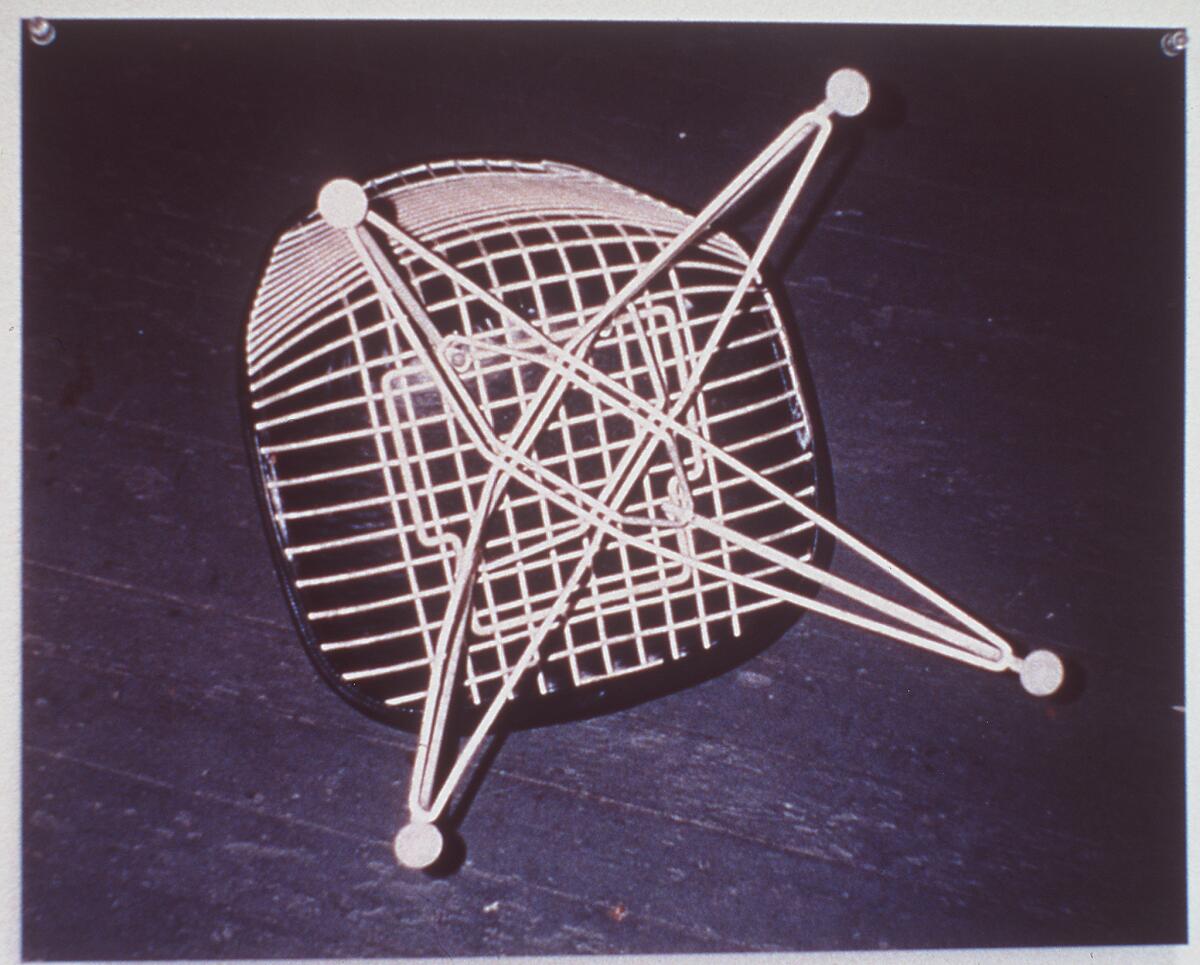

More artwork by Sam Durant

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

Datebook: The concerts of Desolation Center, where art meets performance, a poignant quartet

Could $499,000 in grants that help our soldiers be one reason Congress spared the NEA?

Argentine slums and a Unabomber cabin: How 'Home' at LACMA rethinks ideas about Latin American art

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.