A masterpiece of Baroque painting, missing for more than a century, is hiding somewhere in L.A.

- Share via

A missing masterpiece of 18th-century painting, lost for more than 100 years, has apparently been hanging in a Los Angeles home since the mid-1950s.

Nicknamed “Española” — Spanish girl — after the primped and powdered child that is the painting’s focus, the lost work is from a brilliant set of 16 paintings by

Now it seems the singular gem has been hiding in plain sight — although the exact location of the domestic hideaway remains a nagging mystery.

Ilona Katzew, curator of Latin American art at the

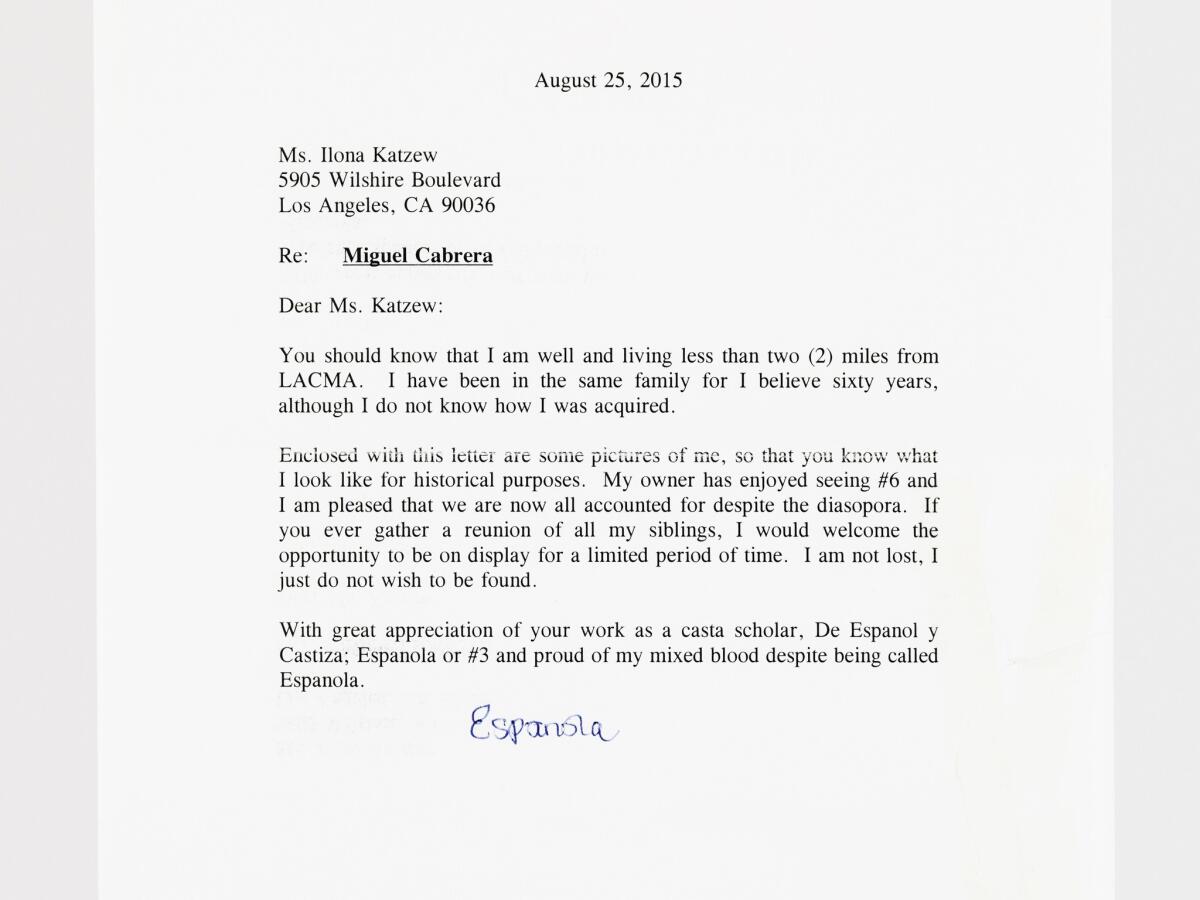

“You should know that I am well and living less than two (2) miles from LACMA,” Española wrote late in summer 2015. “I have been in the same family for I believe 60 years, although I do not know how I was acquired.”

The Cabrera painting is part of a celebrated set of casta, or caste, paintings. In a racial hierarchy devised by white elites during the viceroyalty of New Spain, casta paintings explored the theme of miscegenation, or interracial marriage, among Indians, Spaniards born in Spain, Creoles (Spaniards born in the New World) and Africans.

More than 120 casta sets, typically including 16 carefully numbered paintings, are known. They were painted in different formats by artists of varied skill, including such talented painters as Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz and Juan Rodríguez Juárez. Most sets have been broken up and individual paintings widely dispersed. Cabrera painted only one set, considered the genre's finest.

Two from his suite of 16 disappeared long ago. But one of them — No. 6 in the set — was discovered rolled up and stored under a couch in a Northern California home. Passed down through descendants of mining tycoon John P. Jones, a co-founder of Santa Monica, the painting was a treasured family heirloom about which they knew little. Its owner, Christina Jones Janssen, a retired corporate attorney, decided to research the unusual picture. In April 2015, her astonishing discovery was greeted with great fanfare, landing on The Times’ front page.

LACMA quickly acquired the masterpiece. Katzew is a leading scholar of casta paintings. When she was a young graduate student, her very first research paper analyzed Cabrera’s set. No. 6 went on view just in time for the exhibition “50 for 50: Gifts on the Occasion of LACMA’s Anniversary.”

Española’s owner went to see it.

“My owner has enjoyed seeing #6,” Española’s letter continued, “and I am pleased that we are all now accounted for despite the diaspora.”

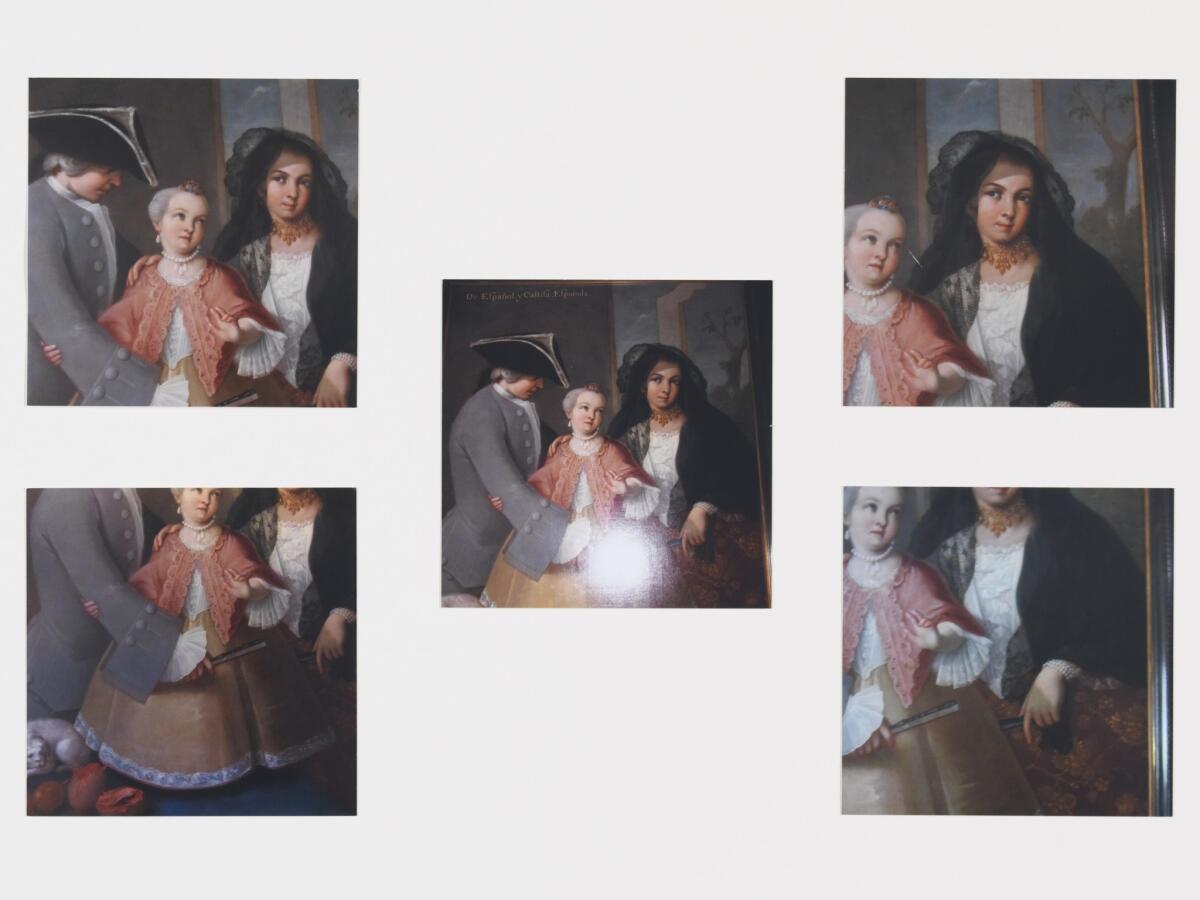

Five snapshots showing details of the painting tumbled out from the envelope. No pre-modern images or even written descriptions of Cabrera’s set are known, but Katzew has little doubt of the painting’s authenticity. Certainty would require examining the canvas in person, but stylistically, and because of its superlative and distinctive relationship to others in the set, the attribution seems sure.

The most complete snapshot contains the reflected burst of light from the camera’s flash near the bottom, obscuring the folding fan held in the right hand of Española’s father. It also shows a fragment of the picture’s modern frame at a raking angle. Given these details, the painting appears to hang on a high wall.

But where? A two-mile radius around LACMA stretches from the edge of Beverly Hills to Hancock Park, from West Hollywood in the north all the way to the Santa Monica Freeway in the south. That’s a lot of houses and apartments.

Española’s letter dropped another bombshell:

“If you ever gather a reunion of all my siblings, I would welcome the opportunity to be on display for a limited period of time. I am not lost, I just do not wish to be found.”

A nearly full reunion had happened nine years earlier, when 14 of the 16 paintings were assembled from museums in Madrid and Monterrey, Mexico, as well as a Los Angeles foundation, for “Tesoros/Treasures/Tesouros: The Arts in Latin America, 1492-1820,” a major exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. They had not been seen together in at least a century.

Española signed her letter, neatly typed in the style of formal business correspondence. But she included no return mailing address, no telephone number, no email address or any other way to contact the owner. The mailing label had even been trimmed, apparently to remove a potentially revealing bit of data.

Katzew’s heart sank.

The curator was well into research on “Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici,” the most comprehensive museum survey ever devoted to the period and set to open at LACMA next month. Cabrera’s castas were painted in 1763, when the century’s premier artist was about 50 and at the height of his powers. “Painted in Mexico” would be the ideal context into which the lost masterpiece could be reintroduced to scholars and the public.

Work on the mammoth show would soon occupy all Katzew’s time. It assembles 139 often monumental, not widely known paintings, many unpublished, and is organized with her art-historian colleagues Luisa Elena Alcalá from Madrid and Jaime Cuadriello from Mexico City. On view now in the Mexican capital, the show will travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York next spring, after it closes at LACMA. Pressed for time, Katzew made a few unsuccessful stabs at trying to locate the mystery owner.

Maddeningly, the stamps on the envelope were not canceled at the post office, which might have narrowed the area of town from which the letter was mailed. Neither are the stamps recent. Thirty-seven-cent stamps were retired a decade before the letter was sent, while the commemorative stamp honoring writer Jack London was issued in 1988.

Katzew took the five snapshots to Samy’s Camera, where notations on the back indicated they had been printed. The store, just a few blocks from the museum, further suggested that the painting could be nearby. Yet, either for privacy concerns or lack of identifying marks, Samy’s was unable to name the snapshots’ source.

Katzew believes Cabrera’s casta set was probably commissioned by no less a personage than the Viceroy of New Spain, Joaquin de Montserrat, Marqués de Cruillas, who returned to Madrid when his term in Mexico City concluded in 1766. The stature of the patron matched that of the artist, and the two were acquainted. Many castas were made for export to Spain to demonstrate that good order was being maintained in the colony; Katzew surmises that Montserrat brought the impressive set home with him.

Eight paintings from the full set are now in Madrid's Museo de América, Europe’s finest collection of Spanish Colonial and pre-Conquest art. The casta that turned up stashed under a Bay Area sofa was bought in Madrid in the 1920s, destined to decorate a Montecito mansion during the Spanish Revival design boom in Southern California.

Could Española have come with it?

It’s the third one linked to Southern California. Another is in the collection of the Rancho de la Cordillera Foundation in Northridge, established around the Mexican art interests of the late Southwest Museum director Carl S. Dentzel and his wife, Elisabeth Waldo, a violinist and scholar of pre-Columbian music.

Five from the set are in a private collection in Monterrey, on loan to the city’s Mexican history museum. Most or all were acquired at New York auctions in the early 1980s, when international interest — and prices — for castas were modest. Experts in the Latin American market estimate the Española painting’s monetary value at around $1.5 million.

Katzew’s calls to the auction houses didn’t yield helpful results. She had to suspend her search.

Now, with her 18th-century painting show finished and set to open at LACMA on Nov. 19, she’s hopeful Española’s owner might drop in to see it — and get in touch again. She’s even prepared to make space for Española on the wall next to her rediscovered sibling.

“3. From Spaniard and Castiza, Spanish Girl,” its full title, is an especially important picture in the set because of its uniquely sumptuous details. The Spanish father, dressed in a dove-gray frock coat and tri-corner hat, is an aristocrat. The castiza mother, offspring of a Spaniard and a mestiza (half Spanish, half Indian), is dressed in regal splendor — embroidered silks, delicate lace, pearls on her wrist and an extravagant coral necklace.

Her refined black-lace mantilla, Katzew says, is virtually unique in the casta painting genre.

So is the painted folding screen in the background, a legacy of expensively imported Japanese art. Mother and father both carry folding fans — a rarity for a man — doubling the emphasis on another Japanese import as an exotic status symbol.

As for little Española, who sports a diadem of flowers above her rouged-porcelain face, she’s swathed in crisp pink and gold silks, costly white lace and a profusion of pearls, often a Catholic symbol of purity. Cabrera’s composition casts the proud trio as a veritable Holy Family.

Why all the visual fanfare?

Perhaps because the third in a casta set represents a momentous occasion: In the conquering white culture’s fabricated racial and social hierarchy, it’s the first time a child miraculously returns mixed-race parentage to purely Spanish identity. A Spaniard marries a Spanish Indian woman, and in the crazy casta world, that’s enough European blood to consider their child fully Spanish.

Española represents a homecoming to the pinnacle of the power ladder. The family is dressed for the occasion, sanctified by luxury.

Cabrera, whose genius as an artist invented these extraordinary visual cues, may have had personal reasons to go over the top. Little is known about him before he emerged in the 1750s as an artistic force in Mexico City. Born in Oaxaca, his own ethnic identity, once thought to be mestizo (Spanish and Indian), is a mystery.

Yet, as Cabrera became successful in the competitive and racially obsessed capital of New Spain, he insistently identified as Spanish. In the hidden remaining link to his magnificent casta set, Española just might embody his anxiety over his own identity.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE ART NEWS AND REVIEWS:

Bellini masterpieces at the Getty make for one of the year's best museum shows

Hollywood & Highland censors sculpture in response to Weinstein scandal

With Pacific Standard Time, Getty finally climbs down from hilltop oasis

Yayoi Kusama's Infinity Mirror Rooms at the Broad: A first look

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.