Review: Wonderfully weird ‘Branchini Madonna’ at the heart of an engrossing Getty show

- Share via

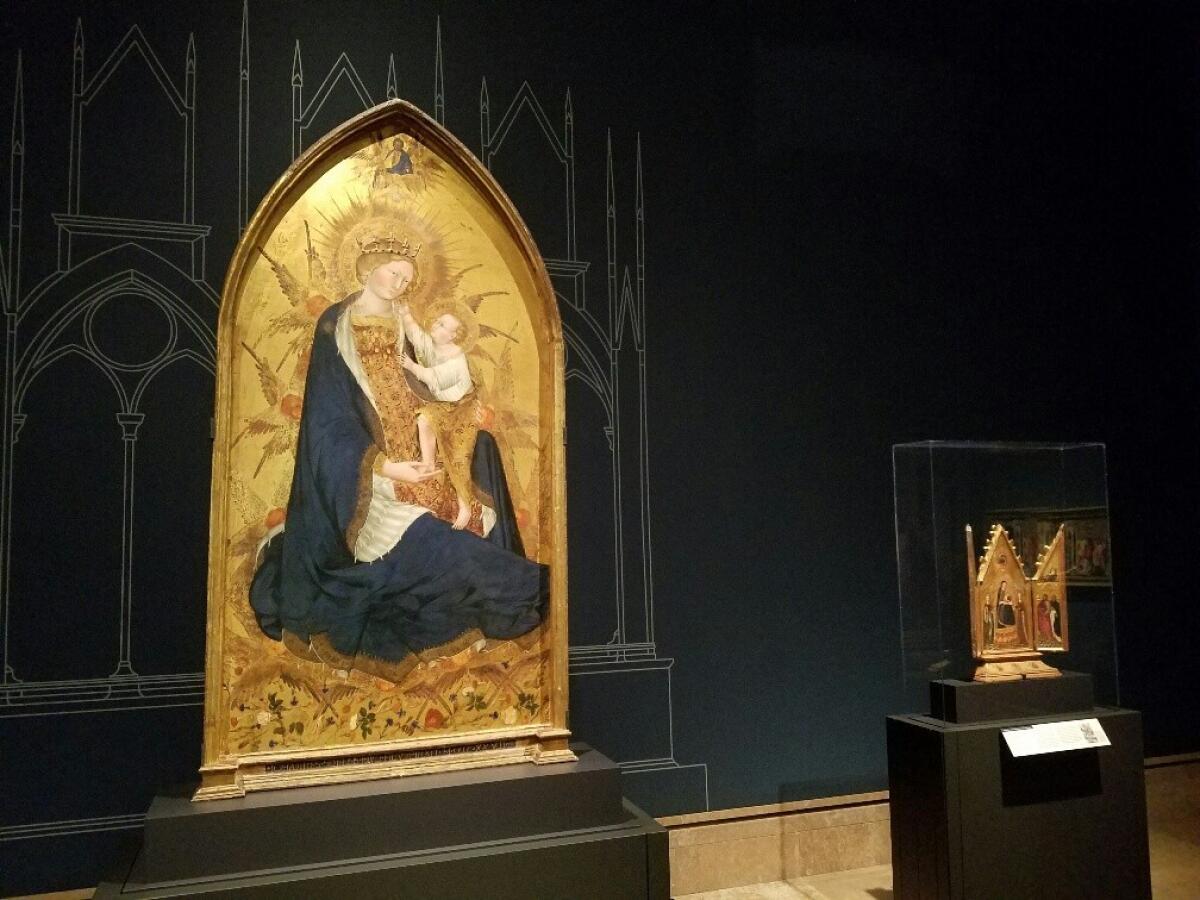

Giovanni di Paolo was barely 24 when he painted the so-called “Branchini Madonna,” a wonderfully weird confection of big, doll-like figures framed within a furious flutter of cherubim wings. The lovely, life-size mother and her inquisitive child are stretched like rubber bands.

Her bodily proportions are all out of whack, he’s a baby giant. The willowy pair rises inside a Gothic arch from a field of flowers set against a light-reflective plane of shining gold. That’s not a sight one sees every day.

The “Branchini Madonna” is among the great treasures of Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum. Currently, however, the monumental painting (it’s 6 feet tall) is installed across town as the centerpiece of a small but engrossing one-room exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

The work is painted on three joined panels of wood in thin glazes of tempera — pigment suspended in egg yolk, which dries to a hard sheen — plus plentiful layers of gold leaf. Some areas, such as the halos and crown, are built up in low relief from thick paste mixed with glue.

The technique, common in Europe before canvas became the norm 500 years ago, creates unique preservation problems since humidity causes wood to expand and contract. The museum, together with the Getty Foundation and the Getty Conservation Institute, has taken a special interest in issues around wooden panel paintings.

That’s how this show was born. The organizers are senior Getty conservator Yvonne Szafran, paintings curator Davide Gasparotto and manuscripts assistant curator Bryan C. Keene. Like the museum’s recent exhibition of Jackson Pollock’s fabled 1943 “Mural,” conservation work on the Madonna, as well as on a related panel on loan from the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands, sparked the idea.

The “Branchini Madonna,” which is signed and dated, was originally at the center of a big, multipanel altarpiece painted for a family chapel inside a major basilica in Siena, Italy. For unexplained reasons, the altarpiece was dismantled some time after 1649, when it was last recorded as being intact. Most of the dispersed panels were thought lost.

Three turned out to be nearby in a local museum, identified only in 2009 as being part of the original ensemble. All of them are here, together with a fourth — the Kroller-Muller’s “The Adoration of the Magi.” The four were part of the altarpiece’s predella, a narrative sequence across the base of the altar.

One predella panel is still missing. So are four large panels that would have flanked the Madonna, probably showing full-length figures of saints.

“The Adoration of the Magi” is a little tour de force of decorative style. The picture’s courtly elegance is a hallmark of established Sienese design, in demand for more than a century.

The kings and their sumptuous royal entourage of attendants, horses, hounds and exotic animals — camels, a monkey — wind through a sinuous S-curve of compressed space between flat, wafer-like hills. The closer the procession gets to the manger, the more dense and crowded the scene gets. The growing hubbub creates a sense of momentous arrival.

As the monarchs wait to pay homage to the newborn, playful details add to the charm. A muzzled dog’s paw rests on his master’s foot, like a proverbial dog in the manger whose potential for interference has been thwarted. Next to them a page similarly kneels to adjust his king’s boot.

A narrative detail in another panel goes to the heart of the altarpiece. In “The Presentation in the Temple,” young Mary has been brought by her parents, Anne and Joachim, to begin her religious education. Giovanni shows her turning her head away from the rabbi to direct her gaze outside the temple. She looks straight at a beggar seated on the ground, lifting his empty bowl.

Abiding faith is linked with service to the poor by this touching gesture, heavenly salvation with earthly strife. In the "Branchini Madonna,” Giovanni pumps up the childhood lesson to triumphal scale.

Mary sits on the ground, like the beggar, but here amid flowers. A Madonna of humility, she’s simultaneously adorned in spectacular regalia as queen of heaven.

The heavenly and the earthly are woven together through myriad devices: the otherworldly flash of gold; the careful, botanical accounting of plant life; the physical heft of otherwise evanescent halos; the rosy blush of human flesh juxtaposed with ethereal bodies rendered in two flat, colorful, elaborately patterned dimensions.

On one level, we see a loving mother cupping her baby’s foot to help lift the child to stroke her cheek. On another, these are alien beings not of this world. The religious doctrine of Jesus as both man and god is expressed.

In 1427, when the altarpiece was made, memories of the pandemic scourge of the Black Death that had wiped out roughly half of Europe — and two-thirds of Siena — were not so far removed. Nor were the ongoing waves of political strife and social instability that the plague’s devastation had unleashed.

A visionary apparition such as Giovanni’s panel was an effective way to celebrate and consecrate the power of an ecstatic, triumphalist, durable religious belief.

The Getty show includes supplementary material that fills out some of the connections and influences on Giovanni di Paolo’s masterpiece. A small altarpiece for private devotion is joined by two lush manuscript illuminations by the artist. Two more illuminations might be by him, while an additional seven by other hands demonstrate formal and conceptual relationships between painted books and free-standing panels.

A priest’s wine-colored velvet chasuble decorated in designs of gold thread and thick, dimensional embroidery connects religious pageantry with the International Gothic style of an adjacent Sienese painting by Gentile da Fabriano. Unusual color harmonies in a slightly earlier panel by Lorenzo Monaco show a bloody decapitation in the martyrdom of Pope Caius.

The Getty also has two concurrent shows that further expand — and nicely complement the view.

One, organized by conservator Nancy Turner, assembles 21 books and six cuttings for “The Alchemy of Color in Medieval Manuscripts.” Artists chose colors for their intrinsic visual appeal. But sometimes they also represent spiritual transformation through the pseudoscience of alchemy.

“The Art of Alchemy,” organized by rare books curator David Brafman in the gallery of the Getty Research Institute, explores the fascinating history of chemical transformation of matter as an analogy for the creation of art. Featuring books, drawings, sculptures, paintings and assorted ephemera, the show ranges far and wide across cultures and time periods.

To cite one: An exquisite, jam-packed little cabinet picture by Joachim Wtewael, the eccentric Dutch Mannerist, shows the Roman myth of Venus cuckolding Vulcan with Mars, an indiscretion exposed by Mercury. It is a cautionary tale of private betrayal and public humiliation.

Yet, given the show’s ancient alchemical context, something else is revealed. The gods are also associated with metals. An impossible bonding of copper (Venus) and iron (Mars) was shown to the god of metallurgy (Vulcan) by Mercury. And that’s a chemical wedding that is just not meant to be.

------------

“The Shimmer of Gold: Giovanni di Paolo in Renaissance Siena"

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through Jan. 8; closed Mondays

Information: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO:

Polly Apfelbaum's secular chapel of abstract art

Tacita Dean's remarkable hand-drawn cloud prints at Gemini G.E.L.

Abraham Cruzvillegas' deft view of L.A. car culture at Regen Projects

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.