Review: Jordan Nassar at Anat Ebgi: Palestinian cross-stitch art as boundary-breaker

- Share via

If only negotiations between Palestinians and Israelis could work themselves out as respectfully and inventively as Jordan Nassar has negotiated the divergent forces feeding into his work.

A Palestinian American from New York who’s married to an Israeli, Nassar has said that he was "born into the conflict." His first solo show in L.A., however, feels like an oasis of calm. The work at Anat Ebgi gallery's AE2 space is politically charged and impassioned, but it’s whisper-quiet. It feels delicate yet has tremendous power.

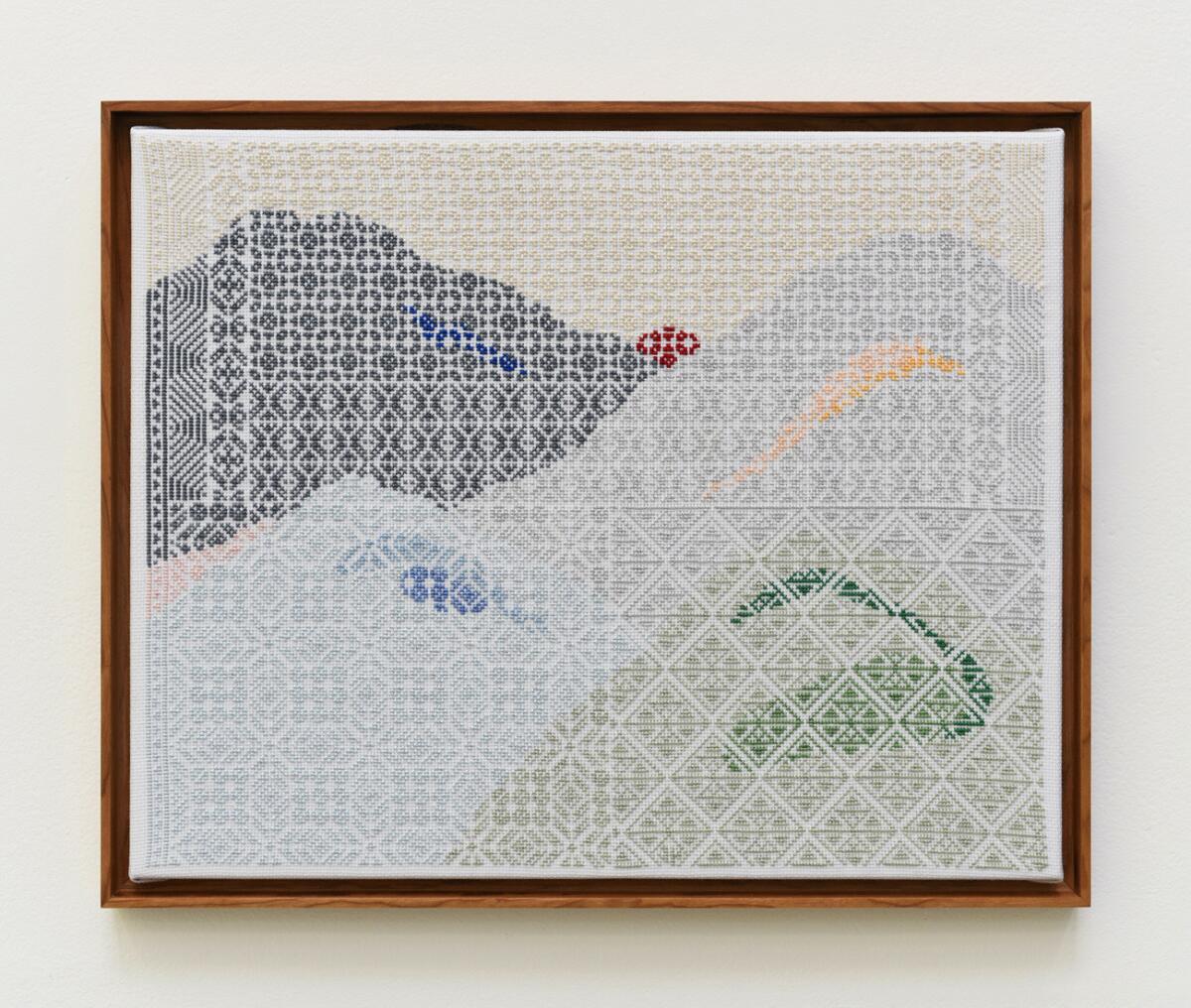

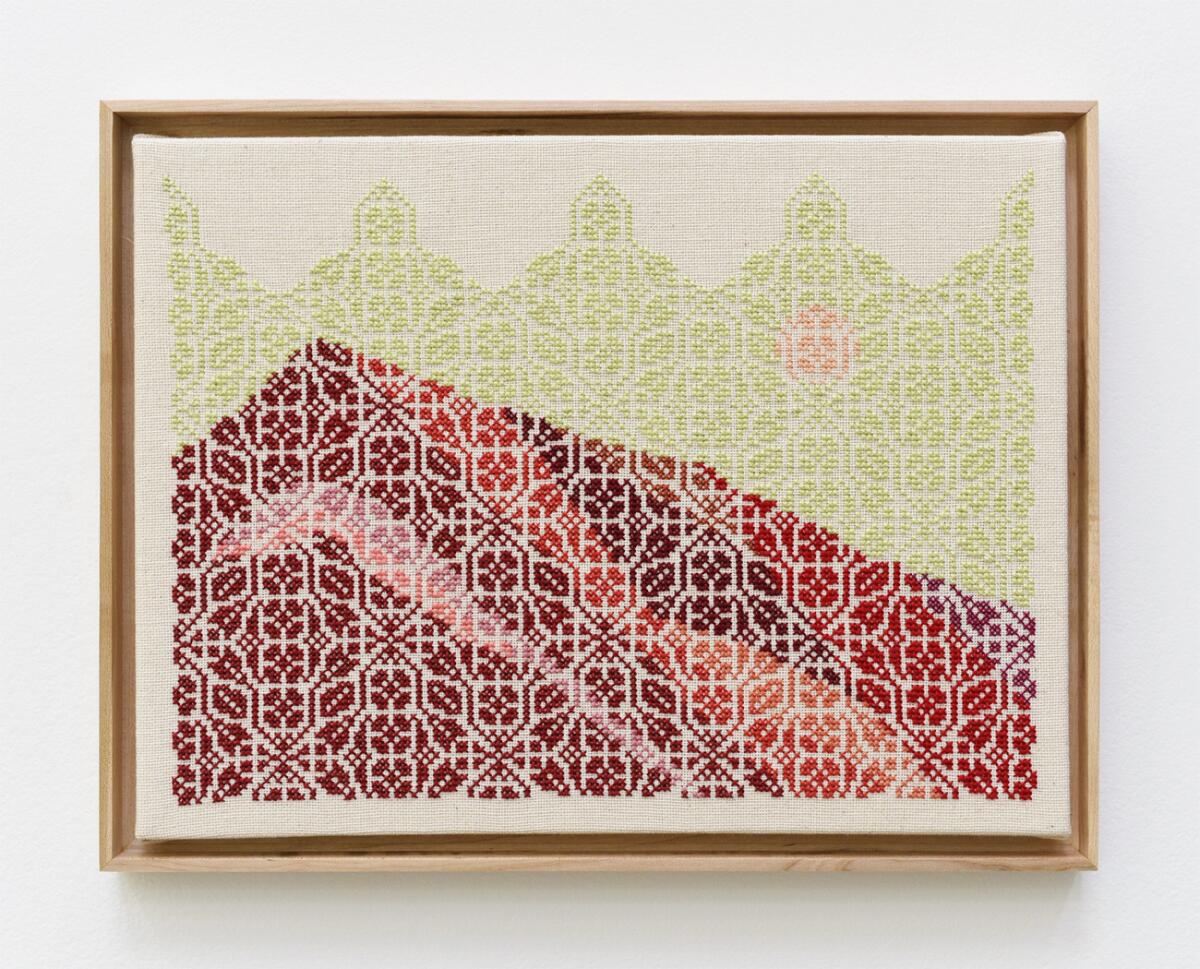

Nassar bases his work on Palestinian tatreez cross-stitch embroidery, typically sewn on panels that are joined into garments or used on domestic items. The cotton-on-canvas panels stretched and framed here retain a modest scale, many of them just 8 inches by 10 inches. Nassar's stitched patterns riff on traditional geometric borders, foliate and floral motifs, but his thread colors don't necessarily correspond to those designs. Instead, they articulate distilled landscapes of receding, silhouetted hills in shades of emerald, wheat, pomegranate and mustard.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

A rich, animating tension emerges between pattern and the pictorial, between the fabric's surface and the deep view of the image sewn upon it. The ancient cross-stitch technique reads to contemporary eyes as a kind of pixelation, even as kin to pointillism. Each stitch is an intimate module positioned on a grid, minimalist in practice but elegantly post-minimal in tactility.

If the patterns and colors of traditional Palestinian embroidery told stories of place and belonging — indicating, for instance, a village of origin — Nassar's work too addresses issues of identity. As a man, he is claiming a place within a custom passed down among generations of women. By his very practice, he helps dismantle the tired hierarchy distinguishing art from craft.

And then there is the bigger, daunting question of ethnic identity, which Nassar touches on in a lovely zine made for the show. Both are titled "Dunya," an Arabic word for the world. Nassar shades the literal definition with emotional and metaphoric import, writing that Dunya makes him think of "the Palestine that might exist only in the imaginations of the Palestinian Diaspora. It is the perfect, magic, dream-Palestine." The beauty of these embroidered meditations is not just visual. Nassar imbues them with reverence, tenderness and hope.

Anat Ebgi’s AE2, 2680 S. La Cienega Blvd., L.A. Through Nov. 4; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 838-2770, www.anatebgi.com

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

MORE ART NEWS AND REVIEWS:

‘Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors’ at the Broad

With Lucas Museum on the way, Natural History Museum plans another makeover

Bellini masterpieces make for one of the year's best museum shows

Two decades after Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao, where does architecture stand?

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.