Review: The 24-hour Joshua Tree party to celebrate Lou Harrison’s 100th birthday

Joshua Tree festivities honor art and music on the composer’s 100th birthday.

- Share via

Reporting from Joshua Tree — A celebratory sun shone brightly. The sky revealed the carefree transparent blue of an unpolluted tropical ocean. The rock formations of Joshua Tree National Park glistened like crystals. The soundtrack for all this Sunday morning splendor was the jovial banging of percussion instruments and jingle-jangle of ankle bells as a motley party marched uphill to the straw-bale house that composer Lou Harrison had built toward the end of his life.

The merrymakers sang an off-key “Happy Birthday” as they reached the imposing yet capricious new gate in front of Harrison House. Made of girders from the Oakland Bay Bridge by Bay Area sculptor Mark Bulwinkle, the gate had its dedication just that morning, becoming an instant landmark.

What is wrong with this idyllic picture of a community heartily commemorating the 100th birthday of a great late American composer whom most of America inexplicably continues to ignore? Could the takeaway be that the neglect isn’t inexplicable? Lovable Lou he unquestionably was, and when people finally come across his music well presented, so does much of it prove.

But Harrison, who died in 2003, remains on the edge of the musical establishment not simply because he challenged norms. That’s the definition of an important artist. What he can’t escape is the lovable part.

In his later years, portly and white bearded, bedecked in his overflowing red shirt and bolo tie, Harrison had the reputation of being the Santa Claus of new music. Often pictured at his side was his partner, Bill Colvig, whose full white beard and red shirt doubled the image. You might have found them seated at the gongs of one of the versions of an Indonesian gamelan he and Colvig made.

Harrison was a student of Elizabethan court music, Korean court music, Japanese court music. He was a poet, calligrapher, illustrator, portrait painter, music theoretician (particularly of alternate tuning systems), environmentalist and craftsman. He practiced sign language and espoused the universal language of Esperanto.

I’m probably forgetting something. But this should be more than enough to suggest how easily it is to see Harrison — who wrote music in dozens of styles, ancient and modern, Western and Eastern (and, for that matter, Northern and Southern) as having been a protean amateur. He adored outsider artists and has been treated as one himself by the music establishment.

But what if he were neither amateur nor any more outsider than Beethoven, who railed against the establishment with every new symphony, sonata or string quartet? An illuminating and engrossing new biography by Bill Alves and Brett Campbell is titled “Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick.” They could have just as easily called it “Lou Harrison: Mother of Us All,” given the extent of his influence.

Let’s begin with that out-of-tune “Happy Birthday.” I’m not sure it really was out of tune. There was a sense of enchantment in the chant this time that, while helped by the setting, wasn’t because of the setting. No, the revelers were channeling, whether intentionally or not, Harrison’s interest in pure intervals, not the kind that are compromised by the piano.

The “Happy Birthday” came around halfway through the 24-hour “Lou Harrison 100: A Global Day of Art and Conservation” at Harrison House, which was turned into a center for arts and ecology after his death. The celebration was the main event for the centennial, which has gotten only occasional attention.

Because of his interest in microtones, the annual MicroFest this spring is concentrating on Harrison in concerts throughout the Los Angeles area; there was a splendid one at Boston Court in Pasadena, offering revelatory early pieces not heard since they were written and a preview of alluring interludes to “Young Caesar,” Harrison’s neglected opera that the Los Angeles Philharmonic will mount on June 13 at Walt Disney Concert Hall.

The Bay Area is the other place where Harrison programs are taking place, with small concerts held over the weekend in Santa Cruz, Harrison having lived from the early 1950s in nearby Aptos. But Joshua Tree on Sunday was ground zero.

And sky zero. When I arrived a little after midnight, local engineer, ecologist and astronomer Tom O’Key had set up a large telescope and was regaling night owls about the sky. The telescope was aimed at Saturn, and its rings could be seen with startling vividness.

Night and day, indoors and out, an irregular mix of music and message followed. Trees were planted, and they became a symbol of a composer who planted musical seeds, such as providing both impetus and know-how for the world music movement we now take for granted. Balinese gamelan Burat Wangi (Fragrant Offering) from the California Institute of the Arts ended its evening of traditional music and dance with Harrison’s “Main Bersama-Sama,” mixing jazz saxophone with gamelan. (It works better with the original French horn.) Harrisonian melodic inspiration in this instance became a kind of offering to the fragrant gongs and bells in the cold night air on a stage behind the house.

But the essence of the composer happened to be distilled into an afternoon hour inside Harrison House. The living room — a narrow shoebox shape with a high domed ceiling — has unique acoustical properties that give sound an embracing fleshiness.

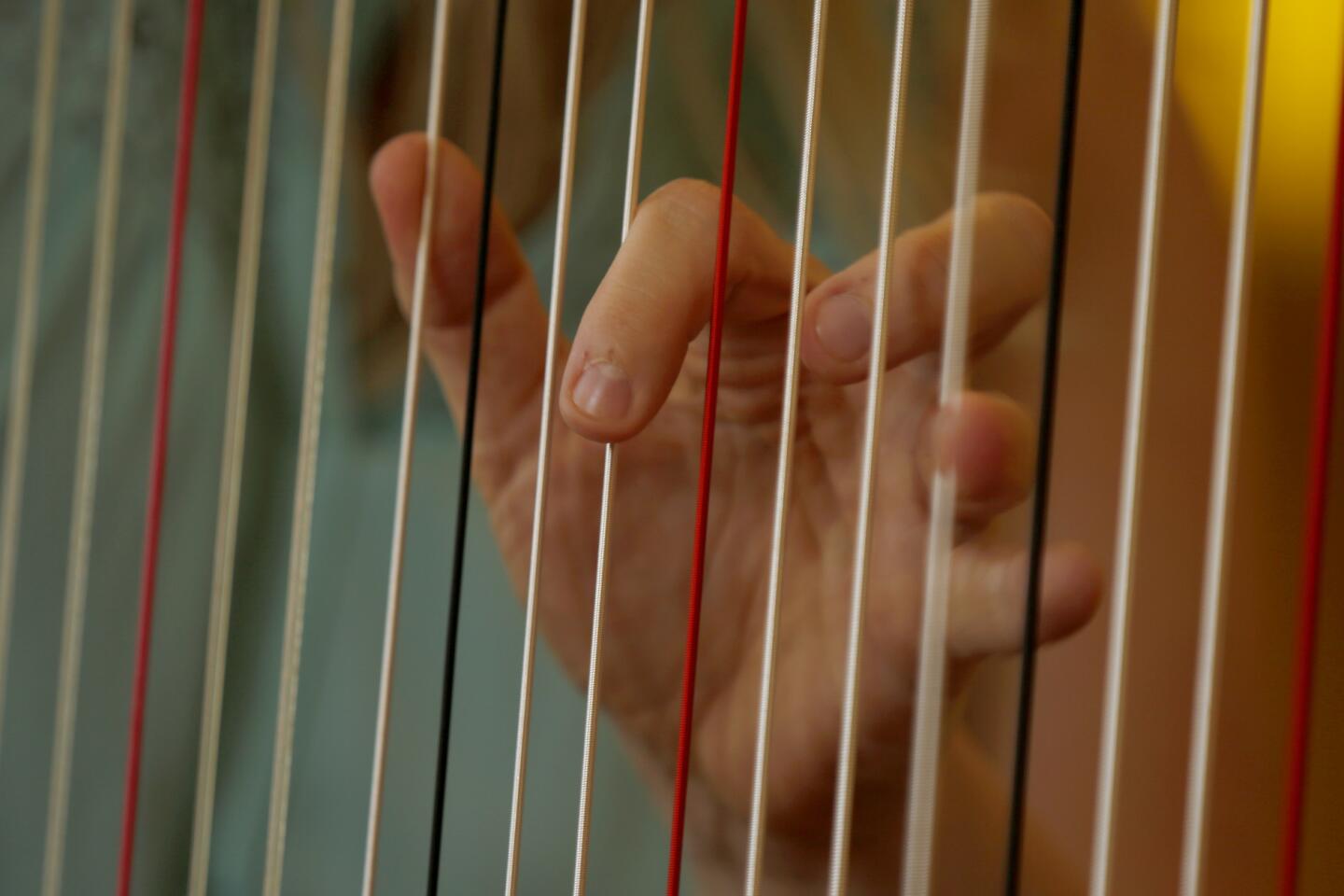

In a gorgeous performance of Harrison’s 1949 Suite for Cello and Harp, Emil Miland’s cello sounded 10 times its size and caused the walls to feel elastic, while Meredith Clark’s harp made the skin tingle. The String Quartet Set from three decades later was given a luminous yet corporeal performance by the Del Sol String Quartet in a room where luminous and corporeal were not antithetic — nor were the evocations of a 12th century troubadour in the first movement or danceable Turkish percussion music implied by the last movement.

It is actually not all that difficult to celebrate Lou Harrison. You need only follow his example. He loved nothing better than celebrating himself, but he always did so by wanting to bring the whole world along with him. To feel better about Harrison, you had to also feel better about yourself and your surroundings, which is precisely the quality of his music.

ALSO

Dudamel has tried to stay out of politics. Now, he’s demanding action in Venezuela

CAP UCLA teams up with Theatre at Ace Hotel: Why shows are moving from the Westside to downtown

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.