Review: Artist Olafur Eliasson built a ‘Reality projector’ of smashing beauty

Just in time for the arrival of recreational marijuana, a massive new light and sound installation by Icelandic Danish artist Olafur Eliasson has opened in Los Angeles.

Atty. Gen. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions might be annoyed, but “Reality projector” is a smashing immersive environment guaranteed to elicit an immediate “Oh, wow” from visitors — pot or no pot. Then, slowly but surely, it unfolds in your eye and mind, deepening into a meditative reverie. Initial amusement transforms into something closer to illumination.

The experience of light becomes enlightenment — which cannot be said about most immersive installations, more often merely brain-numbingly popular entertainments at museums these days. “Reality projector” is the second commission for the large gallery — a former theater — at the Marciano Art Foundation near Hancock Park, and it’s at least as successful as Jim Shaw’s marvelous “The Wig Museum,” which inaugurated the space last spring.

The work is built around highly saturated color produced by shining intense beams of pure white light through monochrome gels. Essentially derived from the film process known as Technicolor, a movie staple launched in rudimentary form a century ago and honed to a fine edge after World War II, the installation resonates against its Hollywood context. Eliasson has deconstructed the process into something new and exhilarating.

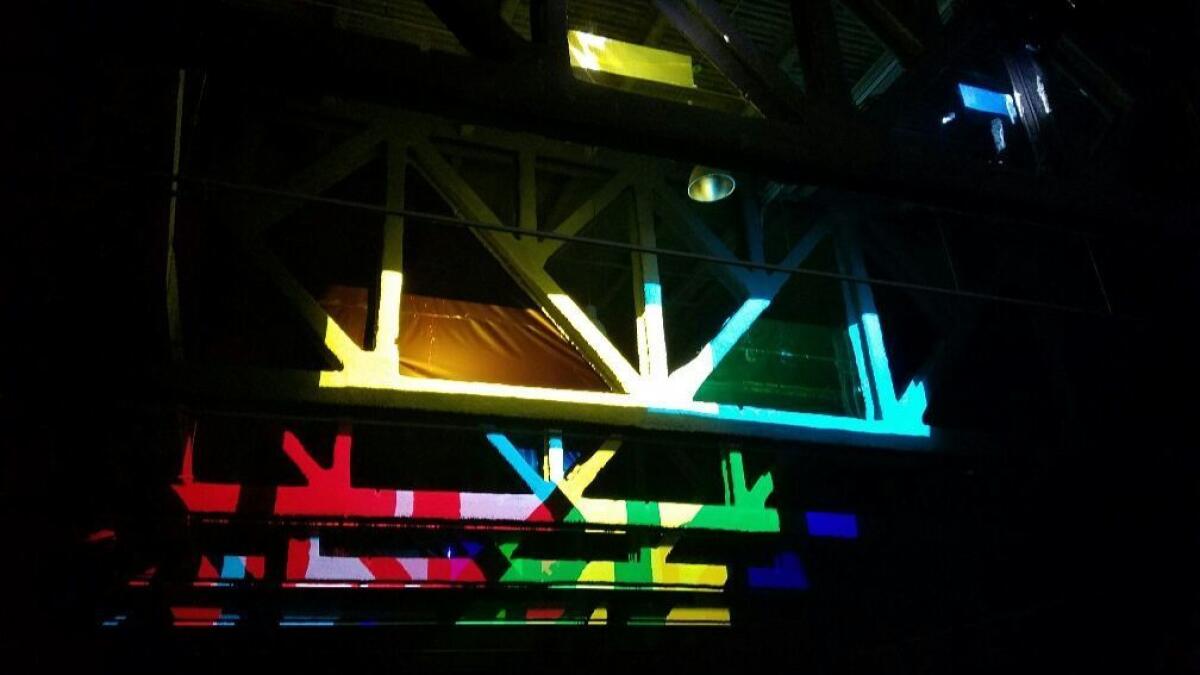

Two mechanized, high-intensity light projectors are set on tracks in the theater gallery’s rafters. At variable speeds they slowly traverse the big space, sliding back and forth.

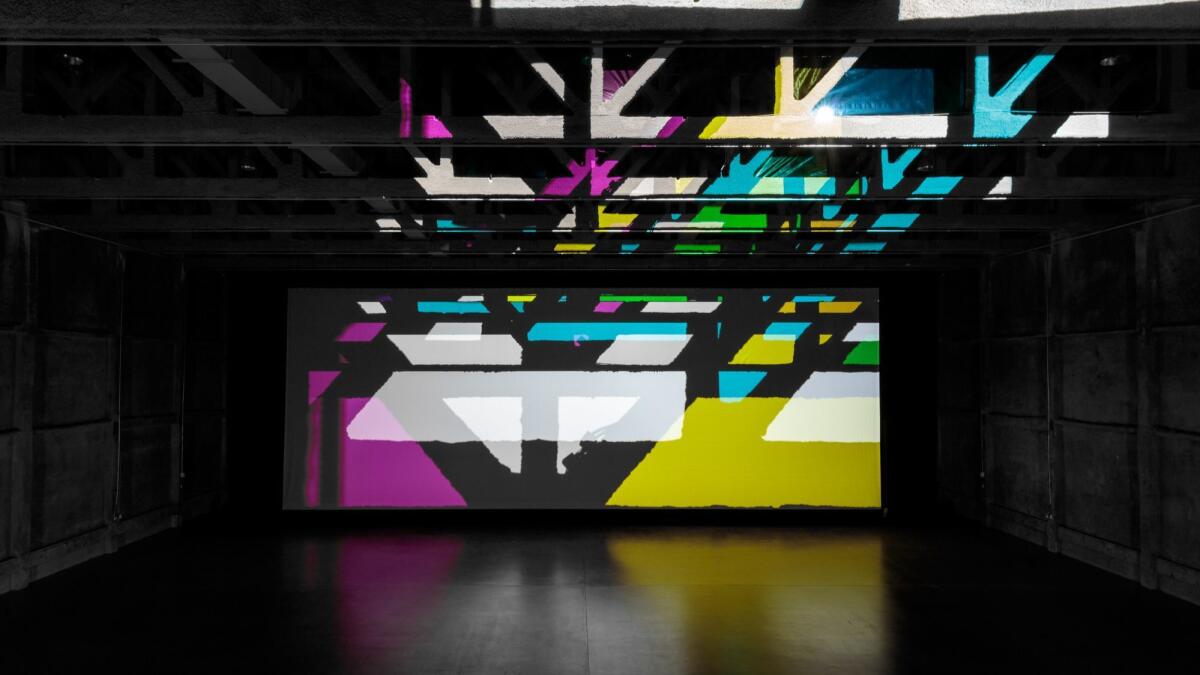

Gels in cyan, magenta and yellow have been inserted into openings between the linear and triangular structural beams holding up the roof. As the tracking light passes through the gels, rectilinear shapes in bright, vibrant colors are projected below onto an enormous screen and set into motion at the far end of the room.

Like an avant-garde animation by Hans Richter or Oskar Fischinger (an avant-garde artist who once worked for MGM), an abstract “movie” of sliding, blooming rectangles, parallelograms, triangles and trapezoids plays across the giant screen — minus the film stock, of course, and blown up to monumental scale. Traditional cinematic editing devices — wipes, dissolves, cuts — are produced by the overlapping, moving shapes, further enlivening the geometric imagery.

Layers of colored light produce a dazzling spectrum of hues, from vivid primaries to surprising pastels. Color shapes are crisscrossed by stark black shadows cast by the overhead structural beams and punctuated by areas of clear white. Think of shadow puppetry, the ancient precursor to movies. “Reality projector,” for all its technical savvy and reliance on modern abstraction, feels strangely primordial.

Because the rafters are spray-coated in fire retardant, the projected black and colored shapes have raggedy edges, yielding an on-screen look of Abstract Expressionist canvases by Franz Kline or torn-paper collages by Jean Arp. Cyan, magenta and yellow roughly correspond to the primary colors in painting, further strengthening the link with traditional visual art.

In concert with Eliasson’s intervention, however, it is the architecture of the room that draws the pictorial composition. The physical realities of place determine the image, which would look very different if installed somewhere else. That place-makes-space precept was born of the European artist’s long-standing interest in such L.A. Light and Space artists as Robert Irwin and Doug Wheeler.

The flowing, ever-changing on-screen image also bleeds into the space of the theater — reflected onto the polished concrete floor, rebounding to the upper rear wall as woozy puddles of amorphous light, tangled in the rafters up above as the projectors and gels do their work. The vast, empty volume of darkened space feels charged.

An extraordinary soundtrack intensifies the experience. “Reality projector” is the 51-year-old artist’s first work to incorporate sound.

A languid, sometimes portentous composition, the sequence of scraping, clanging, creaking, gonging sounds is as aurally prismatic as the colors are visually. At times the ambient sound recalls being in the hold of a mighty ship, listening to the metal heave and strain against the waves, or on a drifting iceberg at sea or in a remote field hearing far-off church bells. The fluidity of space, rarely considered (never mind heard), is underscored and magnified.

The amplified composition was assembled by Icelandic musician Jónsi, instrumentalist and vocalist of the group Sigur Rós, working from a recording Eliasson made in his Berlin studio. That recording is telling. The artist first gathered the noises generated by the process of building a piano from component parts — everything from tightening the tuning pins and laying in the sounding board to ratcheting on the piano legs. These he turned over to Jónsi — “notes” for a composition, as it were.

A live projection evoking a silent film is accompanied by what is in effect a piano score. Sublime cinematic poetry nudges the experience back in time, before our convulsive digital age and before the emergence of talkies.

One reason the work is so eye-grabbingly vivid is that, unlike the electronic pictures flooding across mobile devices and television screens or the ubiquitous computer-generated imagery in movies today, color in Eliasson’s immersive installation is not broken up into pixilated bits hovering in blackened soup. The color is instead pure. The picture is a “reality projection,” and it is beautiful in the extreme.

Marciano Art Foundation, 4357 Wilshire Blvd., L.A. Through August; closed Mondays-Wednesdays. (424) 204-7555, www.marcianoartfoundation.com

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

The mysterious case of Frank Lloyd Wright's Los Angeles houses

Charlemagne Palestine: Teddy bears to the rescue

Marc Chagall and the poetic flight of fancy of 'Flying Lovers'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.