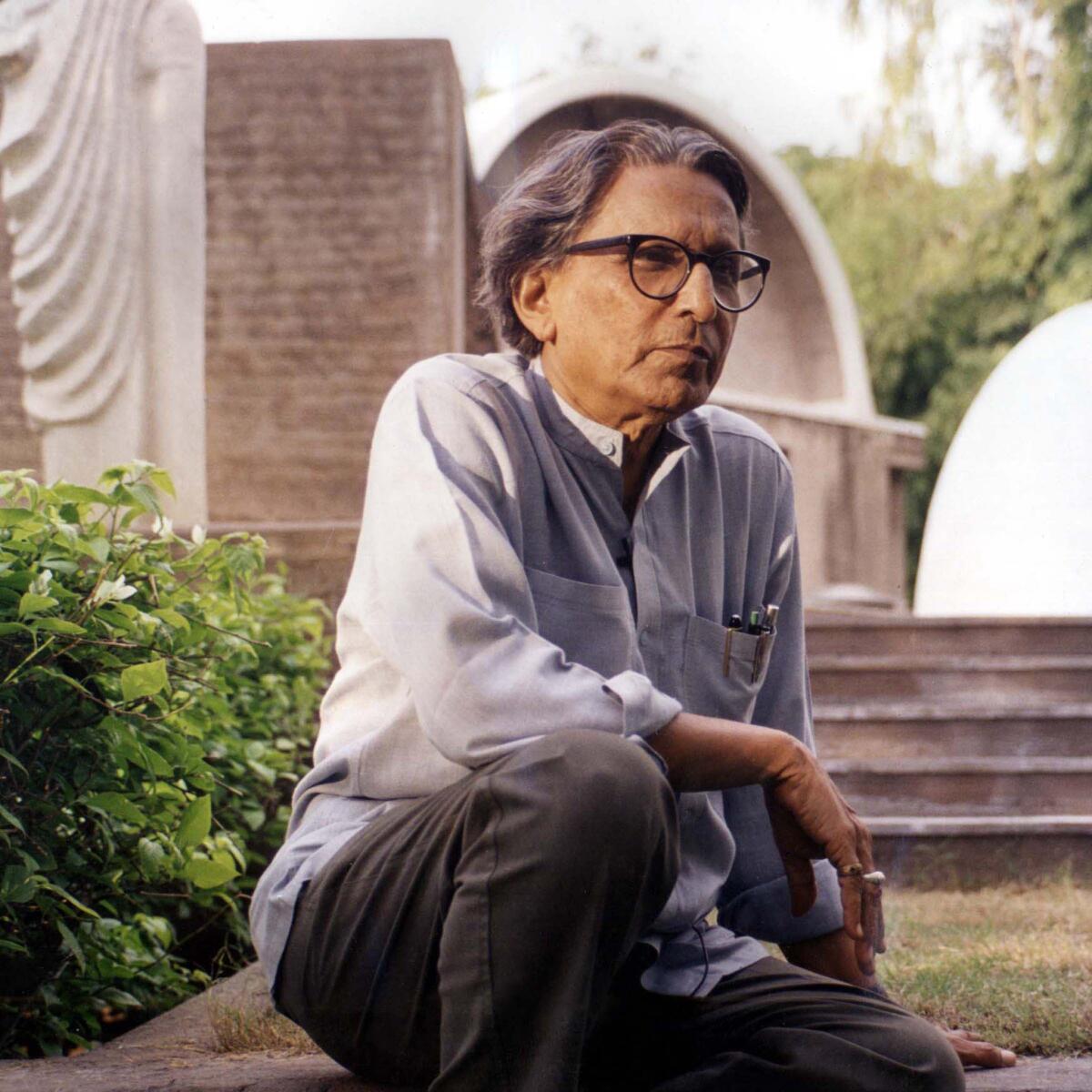

In another surprise choice, Pritzker Prize honors 90-year-old Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi

Extending its string of unexpected choices — and its embrace of an unflashy architecture rooted in regional character and vernacular tradition — the Pritzker Prize jury announced Wednesday that its laureate for 2018 is the 90-year-old Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi.

I don’t find the selection quite as surprising as last year’s, when the Pritzker — among the most prestigious honors in the profession — went to the Catalan trio Rafael Aranda, Carme Pigem and Ramón Vilalta; their firm, RCR Arquitectes, was little known before the news.

Thanks to his collaborations early in his career with Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, Doshi, the first Indian architect to win the Pritzker, is a figure who shows up regularly in histories of modernist architecture and its relationship with India and other Asian countries. He won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, another top honor, in 1995, and was a member of the Pritzker jury from 2005 to 2007. He has taught at American universities including MIT, Rice and the University of Pennsylvania.

Yet because Doshi’s extensive body of work, numbering about 100 buildings, is located entirely in India, he represents a departure from the globe-trotting architects who have dominated the ranks of Pritzker winners since the prize, funded by the Hyatt Foundation, was inaugurated in 1979. Like the 2016 laureate, Chile’s Alejandro Aravena, Doshi has made affordable housing, typically wrought in brick or concrete and with units designed to be modified and enlarged by residents over time, a focus of his work; his massive Aranya Community Housing complex, a collection of apartments in the Indian city of Indore, is home to 80,000 low- and middle-income residents.

“Balkrishna Doshi has always created an architecture that is serious, never flashy or a follower of trends,” this year’s Pritzker jury, which includes Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer as well as Richard Rogers, Kazuyo Sejima, Wang Shu and other prominent architects, said in its citation. His work, the jury added, blends the spare forms of modernism “with an understanding and appreciation of the deep traditions of India’s architecture.”

Writing two years ago in the Architectural Review, William J. R. Curtis noted that the architect’s finest work “draws together both Doshi’s international inspirations and the results of his search for fundamentals in several areas of Indian tradition.” Doshi’s overarching aim, Curtis wrote, is “re-linking modern man with the rhythms of nature.”

Doshi, born in Pune, India, in 1927 into a Hindu family of furniture makers, describes his work in near-spiritual terms. He calls his own architecture studio in Ahmedabad, which he built in 1980, “an ongoing school where one learns, unlearns and relearns.”

After studying at the Sir J.J. School of Architecture Bombay, in what is now Mumbai, Doshi moved to Europe and worked in Paris under Le Corbusier. He returned to India to help supervise the construction of Le Corbusier’s projects in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad; in the 1960s, he played a similar role in seeing Kahn’s Indian Institute of Management to completion.

Superficially, at least, the work of his own firm, called Vastushilpa, seems to offer a blend of those two architects, mixing Le Corbusier’s economy of form and exposed concrete with the rough brick and Platonic geometries of Kahn’s buildings. But Doshi has been ambitious and prolific enough to move well past his mentors and produce an architectural language recognizably his own. An idea of Indian-ness, of expressing national autonomy through architecture, has been central to this effort; he came of age in the wake of India’s independence in 1947, the year he turned 20.

His most significant projects include the Center for Environmental Planning and Technology in Ahmedabad; the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore; 700-seat Tagore Memorial Hall in Ahmedabad, a tribute to the Indian poet and writer Rabindranath Tagore; and the Ahmedabad compound, known as Sangath, that houses his architecture studio.

If Doshi has a trademark it is less a formal or material one than an insistence on extending the public realm and the notion of collective or civic space deep within his layered and spatially complex projects. His residential and institutional designs alike are threaded with covered streets and walkways, overseen by terraces and leading to interior courtyards; his architecture carves out sequences of spaces into which street life can flow.

“Lamenting the degeneration of the city into a place for mere commercial transaction, Mr. Doshi argues for the creation of an authentic public realm of such quality that it will lodge in our memories,” British architect Louisa Hutton said in introducing his lecture at the Royal Academy in London last summer. “He sees architecture and in particular the open spaces between buildings … as being capable of fostering community relationships, social cohesion and, as a result, meaningful lives.”

What he wants people to notice about his work, Doshi has said, is not the buildings themselves as much as “the life around them.”

However you measure Doshi’s relative fame within the world of architecture, there are clear connections between his work and themes that have moved to the fore of profession in recent years. The words that recur in coverage of his architecture — timelessness, weight, power, stillness, layering, equilibrium and the like — suggest an overlap with the work of younger architects gaining prominence in the field and working in places as different as Belgium, Japan and Chile; an architectural mindset that I have elsewhere referred to (with more than a little affection) as “boring” is also clear to see in Doshi’s patient and unruffled approach.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.