The battle of the ballparks: Cubs vs. Dodgers and the lost history of L.A.’s own Wrigley Field

- Share via

The Cubs against the Dodgers. Chicago versus Los Angeles. Carl Sandburg’s “city of the big shoulders” — “stormy, husky, brawling” — taking on the blue-skied, freeway-laced city of the future. A dense tangle of ivy on the outfield walls in one stadium and the clean lines of mid-century architecture in the other.

Baseball’s National League Championship Series, which begins Saturday night in Chicago, would seem to be a classic matchup of architectural and even civic opposites. My counterpart at the Chicago Tribune, architecture critic Blair Kamin, endorsed that line of thinking on Twitter right after the Dodgers finished off the Nationals on Thursday night, calling the NLCS a “dream ballpark matchup” of “transit city park v. auto city stadium.”

Not so fast, Mr. Kamin. Not so fast, Chicago.

Although it’s true that the series is an ideal one for architecture fans — I’d rank Chicago’s Wrigley Field and L.A.’s Dodger Stadium as the two best-designed ballparks in the country, with Boston’s Fenway Park, AT&T Park in San Francisco and the Royals’ underrated Kauffman Stadium rounding out the top five — the history of baseball-stadium architecture in the two cities is more complicated and more fascinating than even some die-hard Dodger fans know.

It turns out, to begin with, that the very first Wrigley Field was located in Los Angeles. It was built in 1925 by William K. Wrigley Jr., the Cubs owner, after he’d acquired the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. (He also helped develop Catalina Island, which is how the Cubs wound up playing spring-training baseball there beginning in 1921.) He found a piece of land at the corner of Avalon Boulevard and 42nd Place, just south of downtown and a fairly short walk from the Coliseum, and put up a ballpark with room for 22,000 fans.

The architect was Zachary Taylor Davis, who had already designed what we now know as Wrigley Field in Chicago as well as Comiskey Park for the White Sox. But Chicago’s Wrigley wasn’t called Wrigley when it was new — it was known as Weeghman Park when it opened in 1914 and as Cubs Park between 1920 and the end of the 1926 season.

The prewar Los Angeles that produced the original Wrigley Field is one we forget about too easily and talk about too little.

— Christopher Hawthorne

Built in a largely Spanish style with a 150-foot-high clock tower marking its front entrance, L.A.’s Wrigley Field was grand by the standards of minor-league parks then or now; reporters called it “Wrigley’s Million-Dollar Palace.” It was friendly to hitters, especially home-run hitters. The Sporting News described it the year it opened as “a real monument to the game,” declaring it superior to Davis’ work in Chicago.

Like much of the civic architecture of that decade in Los Angeles — Bertram Goodhue’s Central Library of 1926, for instance, or the 1928 City Hall by John Parkinson, John C. Austin and Albert C. Martin — our Wrigley aimed for handsomeness and stature instead of embracing the ruthless economy of modernism. With its Spanish and Mission-style motifs, it wasn’t afraid to lean on a largely mythologized sense of regional history and architectural lineage.

The Angels shared the stadium with a second minor-league team, the Hollywood Stars, from 1926 to 1935. In 1939 it was the site of the NFL’s first Pro Bowl. Joe Louis and Floyd Patterson were among the boxers to win heavyweight title fights there.

As an urban object the ballpark was typical of the era, shoehorned tightly into the urban grid, in great contrast to the way postwar baseball parks — Dodger Stadium prominently among them — filled roomier, essentially suburban sites ringed by acres of parking lots. People got there by taking not the freeways but the boulevards, some in their own cars and many more by streetcar.

It wasn’t long before our Wrigley Field was discovered by Hollywood. The silent film “Babe Comes Home,” starring Babe Ruth, was shot there in 1926. In the 1950s, parts of “Angels in the Outfield” (1951), “Fear Strikes Out” (1957) and “Damn Yankees” (1958) were also filmed there.

By that point televised baseball had begun to eat away at attendance in the minor leagues. But L.A.’s Wrigley wasn’t quite done yet. As soon as Walter O’Malley announced he was moving the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in time for the 1958 season, fans began speculating about where they’d play while a new ballpark was approved and built.

Dodger Stadium is a monument to the ambition and drive that came so easily to 1950s L.A

— Christopher Hawthorne

Wrigley, the Coliseum and the Rose Bowl were the contenders. (O’Malley had bought Wrigley Field and the Angels in early 1957, as he laid the groundwork for the move to Los Angeles.) Ultimately the Coliseum won out. Meanwhile the city took ownership of Wrigley Field as part of the (complicated, controversial) deal allowing O’Malley to build in Chavez Ravine.

Still, it didn’t take long for another major league franchise to arrive in Los Angeles: an expansion team (owned by Gene Autry) with the same name, the Angels, as Wrigley Field’s original tenant. Autry’s Angels played the first and only year of major-league baseball at Wrigley during the 1961 season. They spent four years at Dodger Stadium before moving to their own park in Anaheim in 1966.

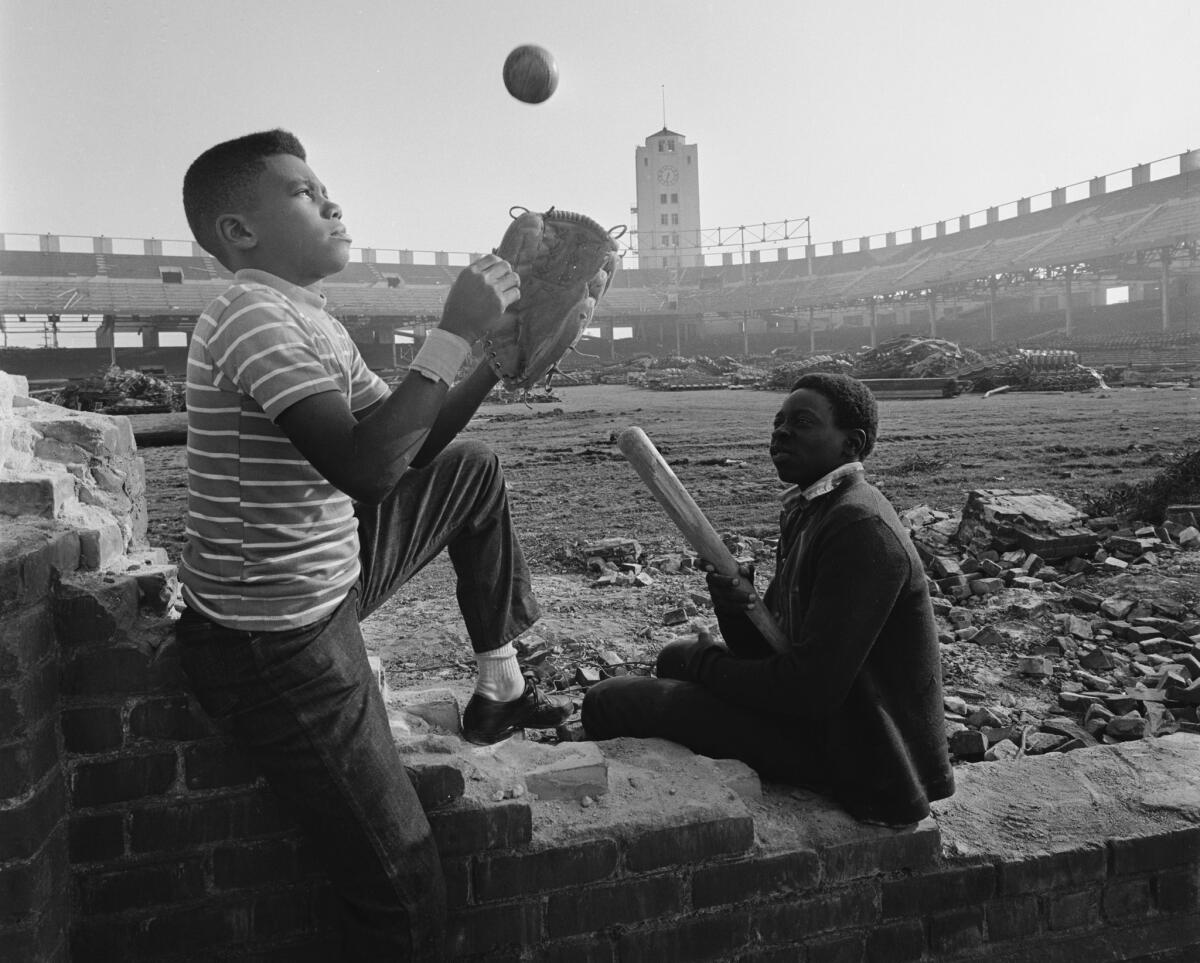

Wrigley Field was demolished in 1969 to make room for the Gilbert W. Lindsay Community Center, part of the effort following the turmoil of 1965 to invest more heavily in South L.A. By that point Dodger Stadium, built by O’Malley and the engineer Emil Praeger in a streamlined, appealingly informal and decidedly forward-looking style, was already cementing its reputation as the finest of baseball’s postwar stadiums.

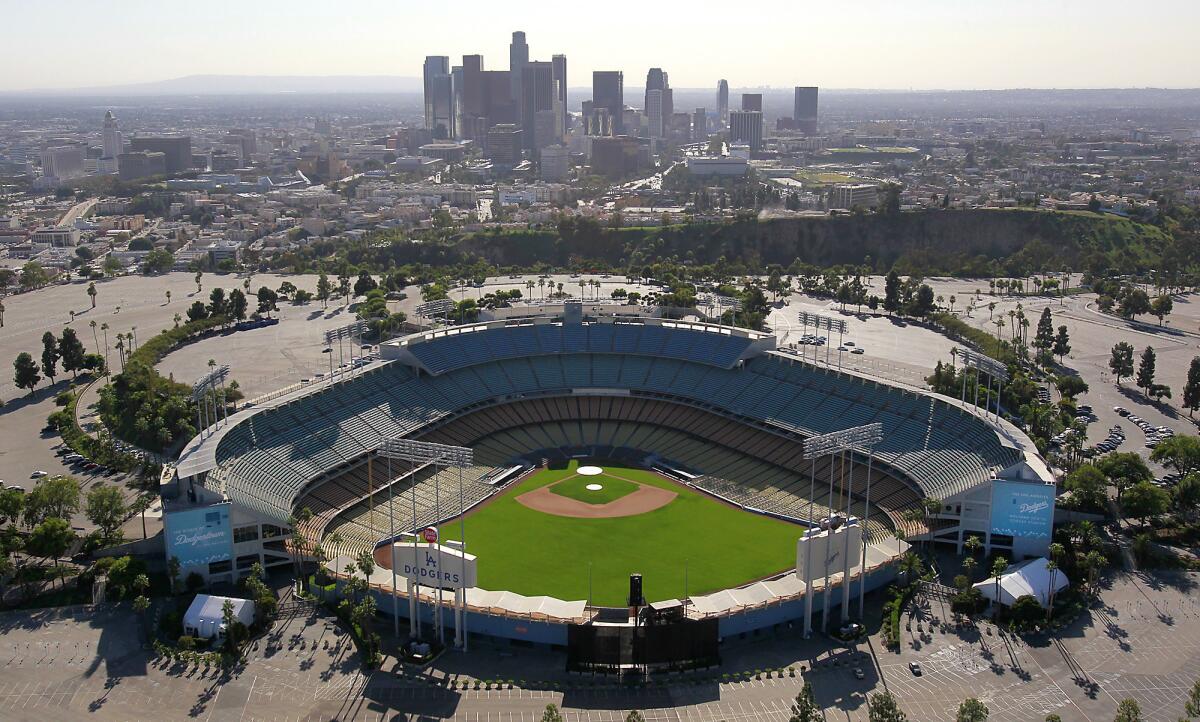

One reason Dodger Stadium and Chicago’s Wrigley belong atop any stadium-architecture list is that each seems so fully and easily to embody its home city. Dodger Stadium is a monument to the ambition and drive that came so easily to 1950s L.A. — a drive inextricable in many ways from the desire to whitewash a complicated racial history that had helped clear Chavez Ravine of its original, largely Mexican residential community in the first place.

Los Angeles was at that point a city that felt justified and even destined to spread and grow in any and all directions. The way the stadium and its vast parking lots find endless elbow room on that site makes that sense of prerogative entirely clear.

The Cubs’ intimate, compact ballpark, meanwhile, has always stood in architecturally for the supremely close — often pathologically, unhealthily close — relationship between the team and its fans.

The prewar Los Angeles that produced the original Wrigley Field is one we forget about too easily and talk about too little. This is in part because its basic architectural and civic qualities were so distinct from the tropes and clichs about freeways, sunshine and self-actualization that continue to define Los Angeles in the popular imagination in much of California, to say nothing of Chicago or New York (or London or Seoul).

That Los Angeles, strung together by a vast streetcar network, was a city whose civic buildings were as ambitious as its private architecture, and whose sidewalks and public realm — especially in and around downtown — were full of life.

As strange as it may sound now, it was a city where even the more famous Wrigley Field — the one where the Dodgers and Cubs will square off Saturday night, a stadium whose architecture we so closely associate with the urban character and scale of Chicago — would have looked and felt right at home.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

What a big Ed Ruscha exhibition misses about Southern California

The most striking thing missing from the first Trump vs. Clinton debate stage

The Arts District’s first-ever skyscrapers would be unlike any other development in L.A.

D.C.’s new African American museum is a bold challenge to traditional Washington architecture

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.