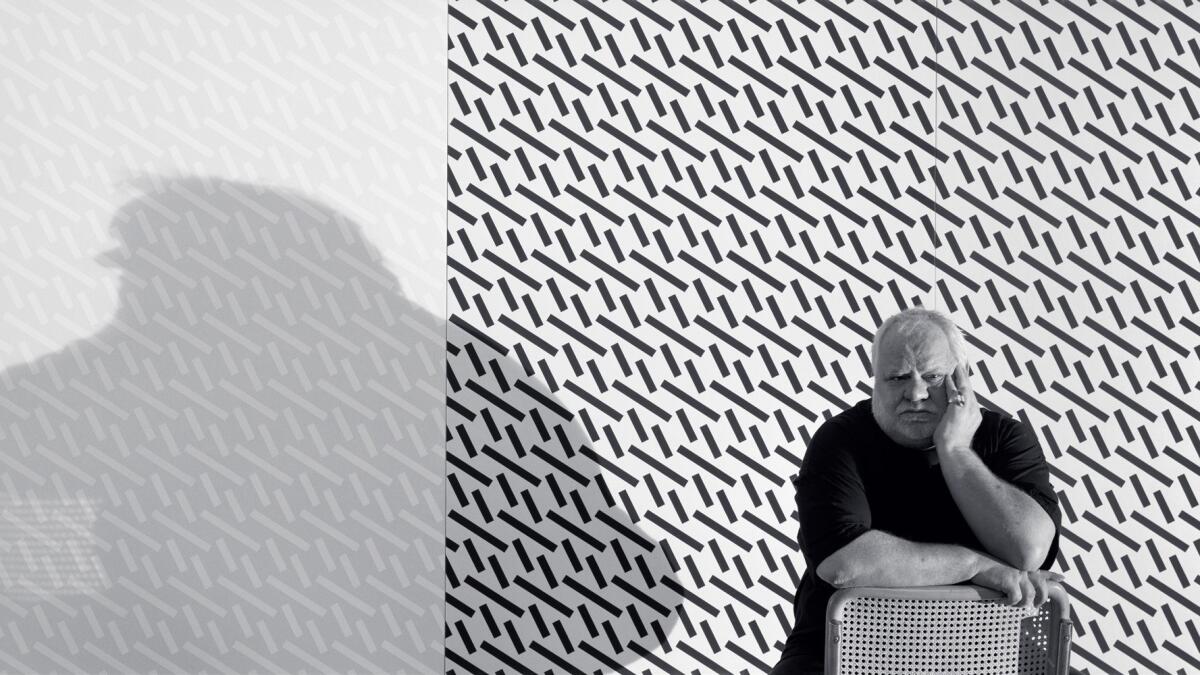

John M. Miller, artist behind painstakingly painted geometric abstractions, dies at 77

- Share via

John M. Miller, a painter of rigorous perceptual abstractions whose work was featured in a special exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2000, died Wednesday after a brief illness.

Miller was stricken Friday during appointments at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in West Los Angeles, according to Lisa Lyons, an independent curator and longtime friend of the artist. He was 77.

Miller was a painter of meticulous abstract geometries. His painstaking canvases built on a tradition of secular spirituality that is a hallmark of 20th century nonfigurative painting.

For the Getty Museum’s acclaimed exhibition “Departures,” Lyons invited 11 artists to make work in response to anything they selected from the permanent collection of ancient, medieval, Renaissance, old master and early modern European art. Miller chose a 500-year-old prayer book.

Facing pages of Jean Fouquet’s richly illuminated “Hours of Simon de Varie,” made in France in 1455, juxtapose a kneeling portrait of a young nobleman, newly installed at the royal treasury under Charles VII, with a regal Virgin Mary and infant Jesus, who are seated on an imposing throne. In response, Miller made three large abstract paintings: “Prophecy,” “Sanctum” and “Atonement.”

Inspiration, a place of solitude and humility — the titles of Miller’s deeply contemplative canvases identify the profound abstract qualities his work shares with Fouquet’s figurative imagery.

Central to Miller’s concerns was the intimacy of the encounter between a viewer and a work of art. Fouquet’s small paintings adorn a private book used for individual prayer, while also depicting De Varie’s personal devotion to the Virgin and Child. Miller’s three large works, each assembled from multiple panels, were installed on three long walls of a large gallery. The environment evoked a traditional triptych format used for centuries in spiritually minded, publicly displayed Western European paintings — albeit without their aristocratic or religious subject matter.

Miller’s abstract paintings, always geometric, partake of the Minimalist virtues of balance, precision and order, standard for that art in the 1960s and early 1970s. Yet, while embracing those brisk qualities, they also entertain such contradictory elements as idiosyncrasy, irrationality and visual repose.

The paintings are composed on raw canvas. Single rows of angled bars of uniform acrylic color alternate with double rows of shorter, angled bars.

Miller first worked out questions of scale in studies and informal sketches sometimes drawn on his studio wall or, later, using a rudimentary computer program. The size of the bars and the spaces between them were adjusted to the planned size of the painting, and a specific monochrome hue was determined. The pattern was then drawn in pencil on canvas stretched over board and, finally, each color bar painted by hand.

The process was laborious and time-consuming. “Prophecy,” the painting that the Getty acquired from the “Departures” exhibition, is 7½ feet tall and 11½ feet wide.

Often, what seems to be dense black in a Miller painting slowly reveals itself to be tinted a deep, rich green, red or blue. The color, sensed as much as seen, emerges from the darkness as one’s eyes gradually adjust to the light. White and a warm, golden ochre were also favorite hues.

On the surface of canvases constructed on a 90-degree axis, the color bars are painted on diagonals just slightly off from 60 or 30 degrees. As with the hues, the eye cannot readily see the minute difference, but the totality of a viewer’s perceptual apparatus can sense it. What appears at first to be buzzy and chaotic soon settles into a crisp, vibrant visual hum. The dynamic pattern creates a vivid tension.

Miller developed his work’s basic composition in 1973, and he stuck with it for the next four decades. Endless subtle variety marks the established format.

A quintessential artist’s artist, Miller cared more for the integrity of his work than for the spotlight of popular acclaim. The late Mike Kelley, an internationally acclaimed Los Angeles artist whose abject mixed-media sculptures and video installations could not be more different, was among his admirers.

The paintings, sometimes mischaracterized as related to the optical trickery familiar in 1960s Op art, instead represent a second generation of the pioneering 1950s geometric abstractions of John McLaughlin, subject of a current painting retrospective at the

Miller was born in Lebanon, Penn., in 1939. After a stint in the United States Air Force, he studied at San Diego State University and Claremont Graduate University, where he received a master’s degree in 1972. Miller taught at Minneapolis College of Art and Design from 1981 to 1983 and at UCLA from 1987 to 1991.

His first solo exhibition was in 1976 at Westwood’s Broxton Gallery (now Larry Gagosian Gallery), followed by a two-person show with Hayward at Sidney Janis Gallery in New York. Miller showed regularly in Southern California with Fred Hoffman, Patricia Faure and Margo Leavin galleries and, most recently, Peter Blake Gallery. In addition to the Getty, his paintings are in the collections of LACMA, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and other American museums.

Miller is survived by his sisters, Shirley Thompson and Barbara Springborn, both in Pennsylvania. No services are planned.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Jim Delligatti, the creator of McDonald's Big Mac, dies at 98

Ron Glass, actor from television's 'Barney Miller' and 'Firefly,' dies at 71

Former NBC boss Grant Tinker, who brought 'Mary Tyler Moore Show' to TV, dies at 90

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.