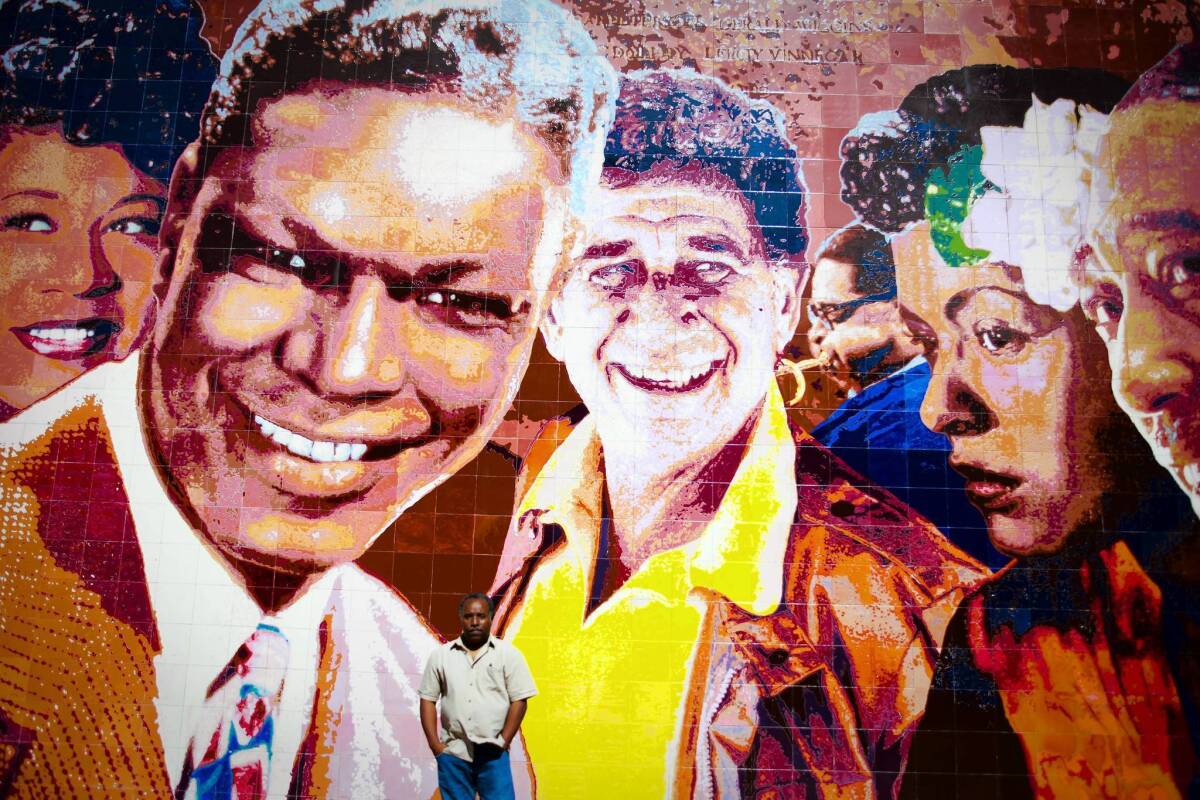

‘Hollywood Jazz’ mural lives on more brightly

When Los Angeles muralist Richard Wyatt Jr. set out in 1990 to create a gigantic public artwork paying tribute to nearly a dozen great jazz musicians, he was given only two specific requests.

“Nat King Cole’s widow [Maria] asked me if I would show him wearing his favorite tie,” said Wyatt, 57, as he stood next to his recently restored mural at the Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood last week.

“And Joe Smith, who was president of Capitol at the time, asked me if I’d please include Ella Fitzgerald,” he said. “Well, I’ve loved jazz my whole life, so that was a no-brainer.”

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The First Lady of Song and Cole — sporting his signature reddish-pink, white and blue tie — now shine a little more brightly since Wyatt set about restoring the mural in November 2011. But the tribute to jazz, which spans an 88-foot-long, 26-foot-high south wall of the tower on Vine Street, was never meant to be around this long.

“Hollywood Jazz — 1945-1972” was commissioned at the request of the Los Angeles Jazz Society, and paid for by the Los Angeles Endowment for the Arts. The colorful piece, which characterizes nine other jazz musicians including Chet Baker, Miles Davis and Billie Holiday and lists the names of more than four dozen other jazz heavyweights, was supposed to grace the wall for only five years. But the mural became an L.A. landmark of sorts.

“Nobody expected the kind of reaction it got,” Wyatt said, noting that it quickly became a popular signpost in movies including “Rush Hour,” TV shows and photographic tours of Hollywood sights to see.

Over the decades, sun, smog and California’s ever-shifting geography left it “horribly faded,” he said, to the point that he could see the original outline marks he painted to guide him.

For the restoration, “Hollywood Jazz” has been re-created from photos of the original, this time fired onto 12-inch-square ceramic tiles for longer life: 2,288 of them, to be precise, Wyatt said.

The restoration was funded by Capitol Records “as a tribute to jazz and a symbol of Capitol’s ongoing commitment to the Hollywood community,” according to a label spokeswoman. “Plus, it’s a beautiful work that has enhanced the Capitol Tower and the city of Hollywood for 20 years, and Capitol wanted to give it the proper restoration it deserved.”.

Don Was, the musician-producer who took over in 2011 as president of Capitol-owned, jazz-centric label Blue Note Records, sees both the beauty of the mural itself and a larger symbolism in its restoration.

CULTURE OF VIOLENCE: Art | Film | Television | Hollywood

“The fact that it’s a jazz mural — not a teen pop-icon mural — was very symbolic of the really broad commitment to music the Capitol group is making,” Was said Friday. That commitment from the parent company, he said, “is being manifested with a mandate for Blue Note [that has] given us the means to be a real home for authentic music. Great what’s been happening in the last few months.”

Wyatt describes the original mural (which took nine months to paint) and the restoration effort (which took 15 months) as labors of love more than additions to his estimable portfolio of works that dot the Southern California landscape. He’s also behind the “City of Dreams/River of History” at L.A. Union Station and “Ethnic Diversity” at the Civic Center Plaza Building in Lompoc.

He grew up in Compton with parents “who both loved jazz, so I would wake up in the morning to the sounds of John Coltrane.”

A sidewalk chalk portrait of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. that he drew when he was 12 for the Watts Chalk-In won $200 at the contest. He now looks back at it fondly as “my first piece of public art.”

Creating the tiles for the new incarnation of “Hollywood Jazz,” he said, required a lot of flexibility because of the idiosyncrasies of the firing process, subtle differences in paint colors as they went through firing and other variables.

“It required a lot of improvisation,” he said. “In that way, it’s a lot like jazz.”

Twitter: @RandyLewis2

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

VOTE: What’s the best version of ‘O Holy Night’?

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.