How the black radical female artists of the ‘60s and ‘70s made art that speaks to today’s politics

- Share via

In scale, it is small — barely 18 inches tall — but its message couldn’t have been more explosive when Los Angeles artist Betye Saar turned a vintage California wine jug, with a label featuring a handkerchief-bedecked mammy, into a sculpture of a Molotov cocktail. Imprinted on the bottle is a black power fist. It’s degrading kitsch remade into fiery cultural armament.

The 1973 sculpture, part of “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85,” which opened at the Brooklyn Museum in April and is now at L.A.’s California African American Museum, had not been on public view since Saar made it 44 years ago.

“Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail,” as the piece is titled, was one of a series of works in which Saar weaponizes — figuratively, at least — racially charged black collectibles, often smiling mammy figures who brandish pistols or grenades. In the case of “Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail,” the entire vessel takes on the guise of a weapon.

“I wanted to empower her,” Saar said of Aunt Jemima in 2015, referring to another of her pieces. “I wanted to make her a warrior.”

The display of Saar’s Molotov cocktail sculpture represents a keen bit of sleuthing by the show’s co-curators, Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley of the Brooklyn Museum (Hockley is now at the Whitney Museum of American Art).

Morris came across a parenthetical reference to it in a feminist art journal. But no photos or other documentation existed. Intrigued, the curators checked with Saar’s studio, but the piece had been out of her hands since the ’70s. Saar, though, keeps records of all her transactions. By combing through old ledgers, the curators tracked “Cocktail” to the SoHo home of a lawyer who used to work for Saar.

“It’s been there since the ’70s,” Hockley says. “That was a special moment.”

“And the Brooklyn Museum was subsequently able to acquire it,” Morris adds. “I’m totally thrilled about that.”

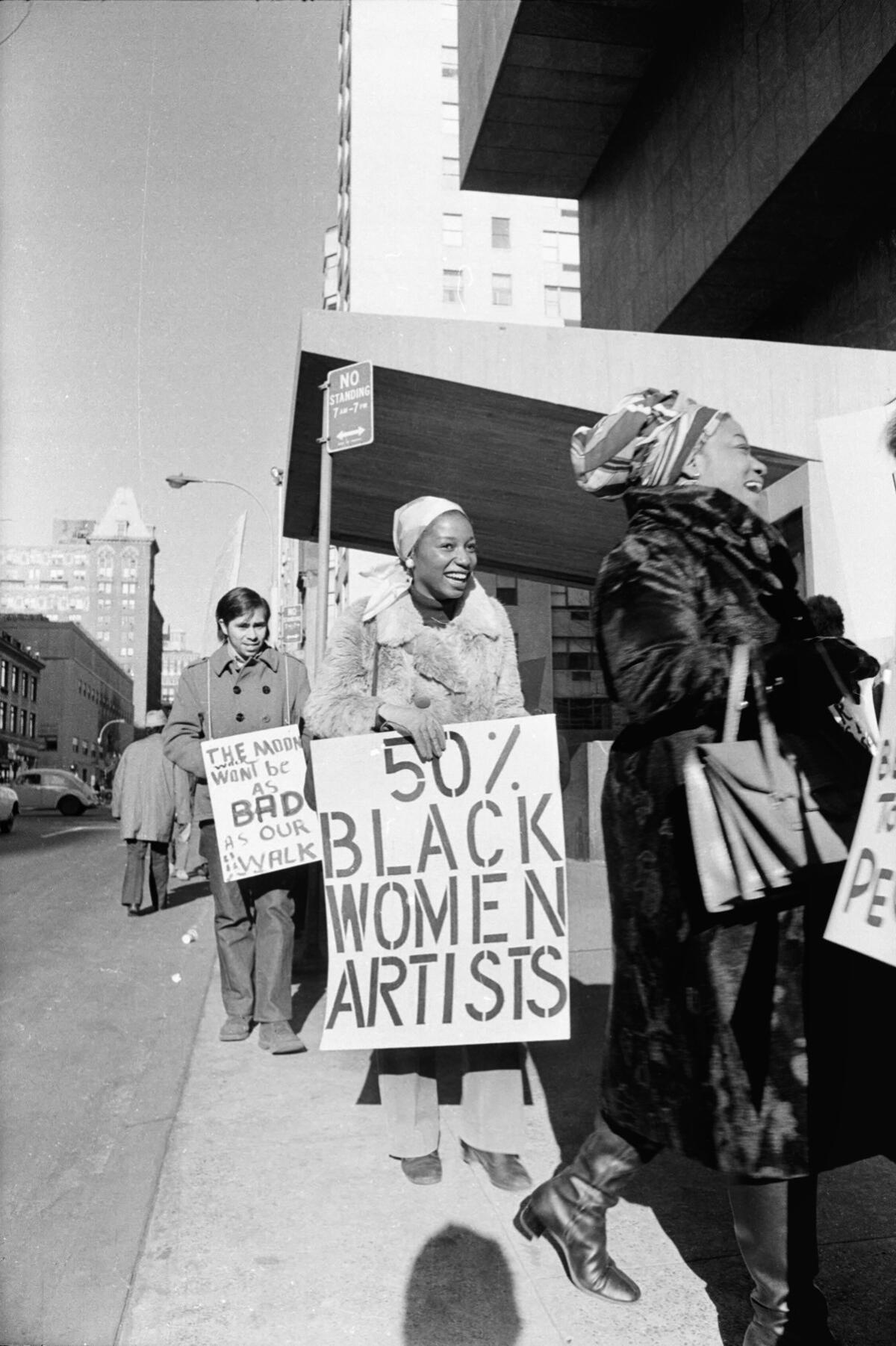

“We Wanted a Revolution” has unearthed all manner of important works from personal archives, private collections and other arts spaces. This includes the understated architectonic sculptures of Beverly Buchanan; outfits by Jae Jarrell, whose work straddled the line between fashion and art; and prints and collages by Kay Brown, who along with five other artists in 1971 helped organize a key New York exhibition of art by black women titled “Where We At.”

“The title,” Brown later wrote, “depicted the significant role of the Black woman artist and showed the community that we did exist — in numbers.”

“We Wanted a Revolution” shines a spotlight on those numbers and on the conditions under which African American women artists labored in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

All of it points to the unique issues black women artists faced (and continue to face) as women and artists in a society in which race plays a defining role.

“Black women were trying to find room for themselves as women, as black, as artists, as activists and how to manage and deal with all of those things,” Morris says. “The question was, do you align yourselves with the black power movement and deal with sexism in that context? Do you align yourself with feminism and deal with racism in that context? There is always a battle to be fought.”

The exhibition began as a way to mark the 10th anniversary of the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, where Morris serves as senior curator.

“The Sackler Center houses ‘The Dinner Party,’ one of the iconic pieces of second wave feminism,” says Morris, referring to Judy Chicago’s 1970s installation that presents world history from a female (anatomical) perspective. “Judy’s piece is revisionist history. So it’s time to take a look at the history of feminism and revise that as well.”

The Sackler, Hockley says, “hasn’t really grappled with race and class and with all of the facets of individual experience. So one of the things we wanted to do for this anniversary was say, ‘Hey, let’s talk about it.’”

The discussion couldn’t be timelier.

THE YEAR IN REVIEW: 2017 in Arts and Entertainment »

For one, the show lands in Los Angeles at a moment in which 1960s-era feminism is already being questioned and revised. Across town, at the Hammer Museum, “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985” (on view through Sunday) looks at the ways in which Latin American and U.S. Latina artists contended with their own questions of exclusion and repression.

On a broader level, there is the current U.S. political landscape to consider. The marked social and political differences between white and black women have come to the fore over the last 18 months. Noted in many post-presidential election analyses was the fact that Donald Trump, despite his derogatory statements about women, drew a majority of the white female vote. The same goes for Alabama’s recent special election in which conservative Senate candidate Roy Moore drew 63% of the white female vote — while 98% of black women voted for Democratic Party candidate Doug Jones (who ultimately triumphed).

All of it points to the unique issues black women artists faced (and continue to face) as women and artists in a society in which race plays a defining role.

“White supremacy and patriarchy are linked,” Hockley says. “They are both about power and oppression based on identity.”

“We Wanted a Revolution” examines what feminism and other issues of art and activism looked like from a black female perspective in the latter decades of the 20th century.

The show is loosely organized around critical movements and spaces. This includes Just Above Midtown (JAM), the pioneering New York gallery focused on artists of color; the group AfriCOBRA, which promoted African American pride and the development of an African American aesthetic; plus a special issue of the feminist journal Heresies that was devoted to race. (Many writings from the era — including a stirring essay on black women and white feminism written by Toni Morrison in 1971 — are compiled in a related sourcebook that is also worth exploring.)

Greeting visitors to the exhibition’s first gallery are a pair of paintings by Emma Amos, the only female member of Spiral, an early collective of African American artists in New York City that included now-celebrated figures such as Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis and Hale Woodruff.

Amos had to submit work to be considered for admission. “They were very nervous about having a woman in their group,” she later said. “They wanted to make sure I was a real artist and not a dilettante or something.”

In one of Amos’ paintings, a 1966 self-portrait, the artist determinedly meets the viewer’s gaze as she arranges a flower bouquet.

Other groundbreaking works include a dress worn by Lorraine O’Grady for her satirical piece “Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire” — made entirely of white gloves. The outfit was used in early-’80s performances in which O’Grady crashed art world events as a persona ironically titled “Miss Black Middle Class.”

White supremacy and patriarchy are linked. They are both about power and oppression based on identity.

— Rujeko Hockley, curator

“It was an indictment of the white institutions needing to take notice of the African American institutions right under their noses,” Morris says. “It was a very brave performance.”

The multifaceted Faith Ringgold appears in myriad contexts: an early self-portrait from the mid-1960s, a poster she made in defense of the Black Panthers and “For the Women’s House,” a rarely seen canvas Ringgold created for the Correctional Institution for Women on Rikers Island in New York in 1971.

That last painting, Morris says, “has been out of prison only twice since it was made. It was almost completely lost. It was whitewashed at one point. But a guard in the prison saw it and called Faith and then it was restored. That’s all kinds of incredible.”

“Faith is definitely one of the anchors of the exhibition,” Hockley adds. “She is one of the few artists to specifically identify as feminist, to claim that language. And she went back and forth between women artists and revolution. She pops up in all of these different places.”

While “We Wanted a Revolution” focuses on the New York scene, “there are strong L.A. connections,” Morris says. “There were key artists doing important things.”

This includes work by Saar and her sculptor-printmaker daughter, Alison Saar, as well as Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems — who aren’t from California but spent formative years studying at UC San Diego.

Of particular note is documentation from a 1978 performance staged near downtown Los Angeles under an overpass of the 10 Freeway by artist Senga Nengudi (who grew up in the L.A. area, but later moved to New York, then Colorado). In “Ceremony for Freeway Fets,” a piece with masquerade, dance and ritual elements, Nengudi gathered a crew of fellow artists, including painter David Hammons and sculptor and installation artist Maren Hassinger, who also has work in the current show.

Like many of the happenings featured in the exhibition, only a few photographs survive — along with the memories of those who participated. But that can be enough to create a legacy, says Hockley.

She points to Rodeo Caldonia High-Fidelity Performance Theater, an ’80s New York collective that staged just two performances — a work of theater and a poetry revue. Even so, its influence seeped into other areas of culture.

Member Alva Rogers become a recognized vocalist and actor. Lorna Simpson went on to wide acclaim as an artist and was the subject of a 2007 solo exhibition at the Whitney. Lisa Jones became a recognized playwright and essayist. (She immortalized the group in her 1994 book “Bulletproof Diva: Tales of Race, Sex, and Hair.”)

“They were these self-realized, confident, sexy young women running in the streets,” Hockley says. “There is so much creativity and smartness and innovation that comes out of these young women. It felt really contemporary. But they had not received a lot of attention because they were short-lived.”

Bringing to life the nearly forgotten story of Rodeo Caldonia is just one more way “We Wanted a Revolution” makes the story of art a little deeper and richer — one that weaves in the crucial American story of what it means to be black and female.

“We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85”

Where: California African American Museum, 600 State Drive, Exposition Park, Los Angeles

When: Through Jan. 14

Info: caamuseum.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

Review: Betye Saar's gun-totin' mammies turn stereotype into power at the Craft & Folk Art Museum

Betye Saar's art on race couldn't be timelier. So why aren't more museums showing her work?

His art centers on African American actors whose film titles 'Fade to Black'

An exhibition on L.A.'s queer Chicano networks shows how California artists connected with the world

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.