Social media have become a vital tool for artists — but are they good for art?

When the Argentine-born, London-educated artist Amalia Ulman moved to Los Angeles in 2014, she spent weeks chronicling the experience on Instagram (@amaliaulman). She posted photos of her shopping binges, her avocado toast and even her plastic surgery: a boob job, natch.

After her move, Ulman became every stereotype of the Westside workout woman, down to the feel-good aphorisms she also regularly posted online. ("Don't worry about those who talk behind your back, they're behind you for a reason.")

None of it — except for maybe the avocado toast — was real. It was a performance, part of a larger examination of the ways in which women depict themselves in public. “Excellences & Perfections,” as the series was called, astutely employed Instagram’s fascination for hyper-pretty perfection to tell a story about a quest for just such a thing (one that involved a truckload of L.A. clichés).

"I was always interested in self-representation and the class divide," explains Ulman, "how people interact with each other and how people represent themselves by what clothes they wear and what signals they send."

As in all other corners of public and private life, the advent of social media has transformed the ways in which artists interact with each other, their public and the institutions that govern their careers.

Services such as Facebook and Instagram have come to be regarded as essential spaces for emerging artists to share their work (or to put it more crassly, find “new eyeballs”). Websites such as Artsy provide earnest how-tos on how to win over collectors on Instagram such as use of hashtags, since these "enable collectors to instantly aggregate an artist’s content and also reveal public support for an artist."

L.A.-based art dealer Stefan Simchowitz has talked about how he uses Instagram to create "heat" and "velocity" for artists he represents. And Hans Ulrich Obrist, the influential curator of London's Serpentine Gallery, posts daily to his account — @hansulrichobrist — a phenomenon he's described as "a movement of some sort."

But the relationship between art and social media is a tricky one. The former is about pushing boundaries; the latter, enforcing them — in the case of Instagram, in a literal square.

Issues of censorship abound. The list of individuals and institutions who have had images removed or their accounts suspended reads like an art world who's who, including the Philadelphia Art Museum, for a pop painting from the 1960s that was deemed too suggestive, and New York magazine critic Jerry Saltz, booted for posting images of Roman and medieval erotica online.

And there are countless other questions about how some of these services — especially Facebook and Instagram, the most powerful — may be quietly shaping the way art is produced and shown, perhaps even motivating artists and art institutions to feature work that looks attractive on digital platforms, even if it feels flimsy in real life.

"We are making up the rules as we all go along," says Rebecca Morse, an associate curator in photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). "This is a topic that social scientists are grappling with — how [a social media platform] is laid out affects the information that people insert into it.”

Certainly, social media can be a difficult space for artists to present ideas or images that lie outside of the gauzy universe of sunsets and cappuccinos.

Facebook's community standards, for example, do not allow photographs of nudity (a.k.a. "people displaying genitals") — which pretty much puts the kibosh on presenting a lot of contemporary photography, not to mention documentation of historic and contemporary performance art. The services, however, do allow users to post "photographs of paintings, sculptures, and other art that depicts nude figures." (Not dissimilar to The Times' publication standards in this area.)

But these are erratically enforced.

L.A. artist Micol Hebron, who goes by @unicornkiller1 on Instagram, has long created images that poke at the arbitrary notions of acceptability on social media, creating nude self-portraits that place artful barriers over the bits that might be deemed offensive — such as Photoshopping acceptable male nipples over unacceptable female ones.

Last December, during a visit to the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, she snapped a photo of another artist’s work — painter Lisa Yuskavage, who is known for producing buxom, kewpie-ish female figures in sherbet-y tones. The painting, titled “Northview,” showed a woman lifting her shirt and examining her exposed right breast.

A few hours after uploading the image, Hebron discovered that she’d been locked out of her Facebook account and the image removed. "Someone complained," she says. "Over a painting! A painting of a woman looking at her own breast. It wasn't lewd or lascivious and it didn't have sexual content at all."

For the offense, Hebron was blocked from accessing her account for 30 days. She later created a self-portrait in the same pose — replacing her nipple with an illustration of a cockroach. She posted the image on Instagram where it remains to this day.

Hebron is hardly the only one to face the arbitrary hand of social media moderators.

In January, an image of Copenhagen's famous statue of the Little Mermaid, a century-old bronze inspired by the children's fairy tale, was removed from a Danish politician's Facebook feed for running afoul of community standards.

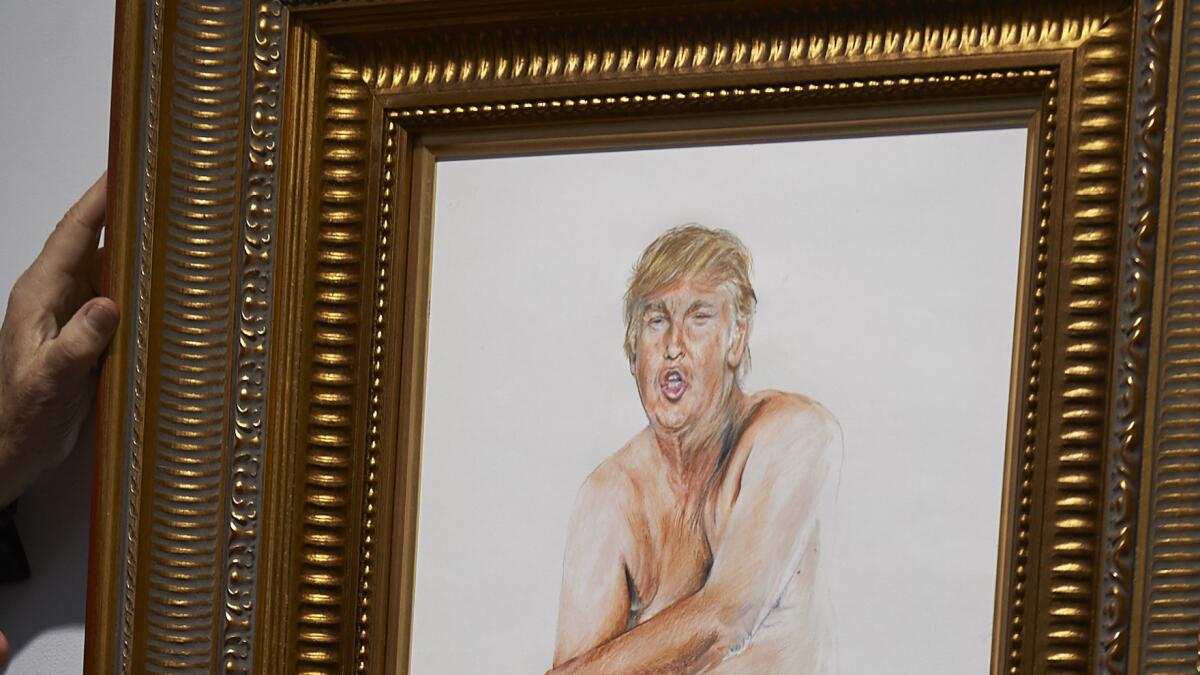

In March, Los Angeles artist Illma Gore made headlines when she was blocked from Facebook for posting a painting of a nude Donald Trump. She was ultimately given access back to her account and the image was re-posted (it is a painting, after all), but Gore says the whole experience was disheartening.

“It’s sad to me to watch it be filtered, like the news or what we see on TV,” she says of Facebook. “That was the saddest part for me — that the communities we have created are quite censored as well.”

Some of the arbitrariness is partly due to the fact that managing standards for a "community" of 1.6 billion people — Facebook's estimated user base — is hardly an exact science.

Contrary to popular lore, there is no algorithm scanning the service for naked butt. Currently, Facebook and Instagram rely on users to flag offending posts. These are then reviewed by employees of the company, who make the decision whether to remove the image and/or block posting privileges.

"It is not always easy to find the right balance between enabling people to express themselves creatively while maintaining a comfortable experience for our global and culturally diverse community of many different ages," stated a Facebook spokesperson via email. "But we try our best."

Even so, the process of being blocked can be bewildering. Paddy Johnson, the founder of the website blog Art F City, had her account frozen after a bot glitch led to a racy animated GIF being posted on the blog's Facebook page. Not only did she lose her privileges, so did everyone listed as an administrator of the page.

And trying to appeal these decisions is an opaque process. "You get an email and it's signed by someone with only their first name," says Johnson. "I received an email from 'Keith.' "

That is not to say that social media haven’t been a boon to art in some ways. They have allowed artists a high level of dialogue with their public.

"And it's changed criticism," says Lauren Cornell, a curator at the New Museum in New York, who also oversees some of the museum's technology initiatives. "A lot of discussion has migrated [to sites like Facebook].”

But it nonetheless remains "a hard place for art,” she adds. "It's kind of like being asked to make art in the showroom of a company. It's a compromised space."

Part of this is due to the very architecture of these platforms.

"Artists shouldn't be making works to get 'likes,' " she says. "They should be thinking about generating conversation. I think about this for myself. I’m not a curator so people can just give me a thumbs up.”

“There is also the issue of artists branding themselves and what that does,” she adds, “how they feel that in order to be an artist they have to create a successful 'brand' on Instagram."

This can lead to an insidious form of self-censorship, says Ulman.

"It's not just about nudity," she explains. "It's about the need to put something up that people are going to 'like.' It becomes this disposable idea."

The rise of social media has likewise seen the rise of the "Instagrammable" art object or installation: Works that look great in a box on a phone but which may be thin when it comes to concept or ideas in the gallery. Random International's "Rain Room" at LACMA is one such installation — a work that serves more as an ideal set for picture-making than it does as a place where viewers can tease out complex ideas about nature.

Some of this may be due to the fact that the types of works rewarded by social media tend to be of one kind — the kind that looks good in a box on a phone. That generally means objects with attractive repeating patterns or works with a graphic punch that render well in two dimensions.

Oliver Leach, a San Francisco-based photographer who eschews Instagram in favor of less restrictive services like Twitter, states: "You don't get the abject in Instagram at all. That's crucial to me. The abject is something you don't want to see — and it's important for art."

All of this, however, does make services such as Facebook and Instagram a system ripe for messing with — which is exactly what artists such as Ulman have been doing.

There are others, too. Laimonas Zakas, the artist known as Glitchr, has long played with gaps in Facebook's code to mess with its boxy, blue format. And, in 2011, conceptual artist Ed Fornieles gathered identity information from a bunch of college students he found on Facebook (against the rules) and used it to create a series of fictional characters that he employed in a long-running online group performance that he also staged on Facebook.

Currently, Ulman is in the midst of another piece — which she is shooting, Instagram by Instagram — in a small office space downtown, in which she dons conservative office wear and hangs out with a pigeon named Bob.

Ulman grew up with the Web and its tropes intrigue her. But they in no way represent the entirety of art to her. Nor is she staging these performances for the sake of "likes."

"Life is not just visual," she says. "Everything has been flattened into an image because of the media, but art is more than images."

"A sculpture,” she adds, “should be allowed to be a sculpture."

MORE:

Is it news or entertainment? The fuzziness of modern life gets operatic in JacobTV's 'The News'

Twitter and Vine loosen limits to hold on to users

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.