Commentary: Perspective: Why political pundits give drama critics a bad name

- Share via

Political pundits have long been giving drama critics a bad name.

Inevitably, in the run-up to an election, some op-ed columnist will make a crack comparing recent political coverage to theater criticism. What is meant by theater criticism in this context is political journalism fixated on the personalities of the candidates at the expense of their policies.

I can think of quite a few star reporters on the campaign trail who might learn a thing or two from reading the drama criticism of Michael Feingold, Frank Rich, Robert Brustein, Richard Gilman, Gordon Rogoff, Stanley Kauffmann, Elizabeth Hardwick, Walter Kerr, Eric Bentley and George Jean Nathan. The focus of these writers isn’t on the suavity of the actors, the glamorousness of the costumes or the grandeur of the sets. Sharing Bentley’s respect for the playwright as thinker, these critics are at their sharpest when tracking the theatrical collision of ideas.

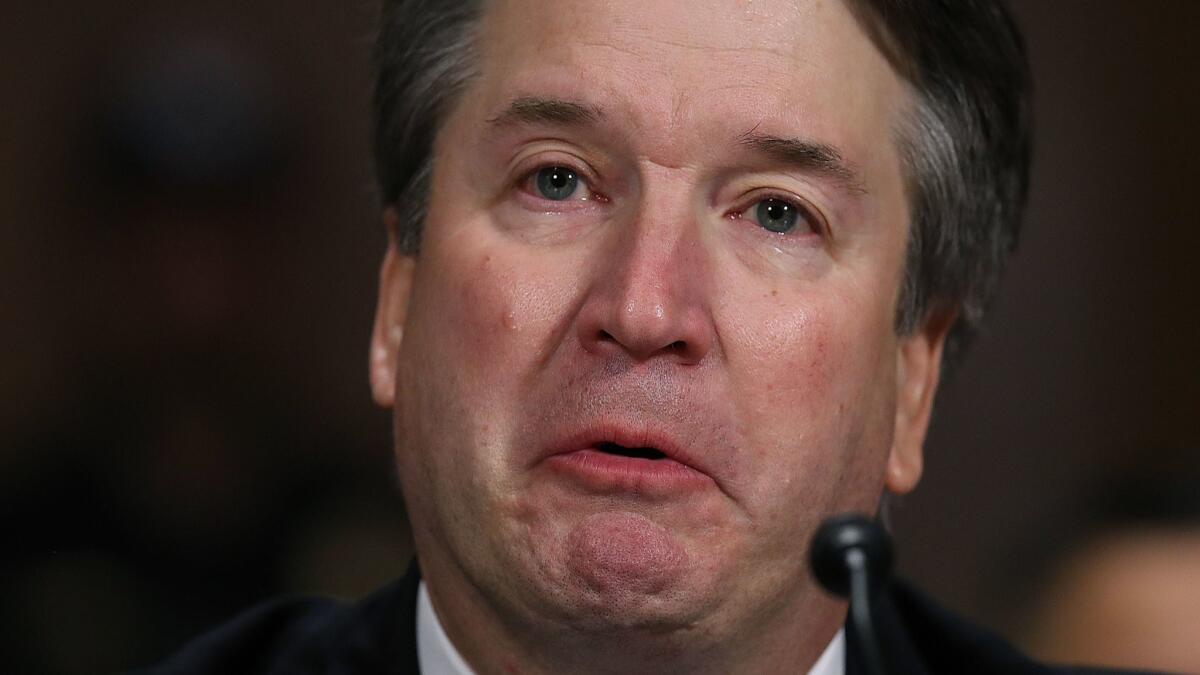

Reading vintage drama criticism could only improve our clichéd political discourse. It was dismaying, to say the least, to hear journalists and politicos resorting to that blandest of critical placeholders — “compelling” — when describing the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford and Brett M. Kavanaugh after their marathon hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee last month.

When a theater critic refers to an actor as “compelling,” it’s a clear sign that the reviewer wasn’t sufficiently inspired to reach for language capable of capturing the hue and texture of the performance. That quite a few talking heads decided that Blasey Ford and Kavanaugh were “equally compelling” told me that safety was more important than nuance to these commentators, who (cowering behind generalizations) would rather proclaim the afternoon “riveting” than sort through more complicated thoughts.

South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham’s upstaging moment at the Kavanaugh standoff was widely described as “dramatic,” with many impressed by the way the Republican lawmaker’s “scene” transformed a bad day for a judge whose histrionics raised doubts about his judicial temperament. Kavanaugh needed Graham to hijack the show, especially after Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) challenged the Supreme Court nominee to turn around and ask White House counsel Don McGahn to call for an FBI investigation into the sexual misconduct allegations made against him by Blasey Ford and others.

Midterms 2018: How politics and the arts are colliding »

Durbin’s tense questioning attempted to corner Kavanaugh into making a choice, which used to be a requirement for a theatrical protagonist. Graham took a more melodramatic tack, throwing a tantrum and hissing out the line, “If you’re looking for a fair process, you came to the wrong town at the wrong time” — as though he were finally granted a juicy supporting role in some overheated courtroom drama on Turner Classic Movies.

The senator’s scenery chewing galvanized Republicans and left many in the media duly impressed. I found the performance less convincing, but a good portion of the public seems to respond to such vehement theatrics. Donald Trump roaring at campaign rallies without concern for factual accuracy or syntactical logic is considered spellbinding not just by the Make America Great Again faithful but also by cable networks still dependent on the president for a ratings bounce.

Historians and political scientists worried about the fate of American democracy have been sending out Cassandra bulletins about what’s at stake in the midterm elections. I share their concern about the rise of authoritarianism, but I’m also deeply troubled about the way the power of theater has been co-opted by those intent on making the electorate more reactive and less accessible to reason.

When Kavanaugh was elevated to the Supreme Court, I took it not just as a failure of bipartisanship but also as a profound theatrical defeat. Refusing to give in to despair before such a crucial election, I decided to reach out to young artists, those in the 18 to 30 range, who have such a dismal track record of voting. I urged my theater students at the California Institute of the Arts to recognize that they have a special obligation to vote, because their métier is fundamentally about truth, empathy and justice.

A U.N. climate report indicating that the dire effects of global warming are happening sooner than expected further prodded me to make my case. My little talk, which turned out to be a fitting introduction to a class on Lynn Nottage’s “Sweat,” endorsed no candidates or party platforms.

My message was simply a plea for those who will be alive longer than I will be to care enough about the future to vote. And not only to vote but also to theatricalize their public commitment to voting.

I suggested that they turn the act of going to the polls into a communal performance. I was imagining a Fellini-esque street parade with party hats, guitars and harmonicas, but decided that such a cinematic allusion would only reveal my age.

The generational gulf between me, a Gen X-er, and my millennial students, is undeniable. Many I’m sure heard a middle-aged guy telling them what they already know or aren’t yet prepared to care about. One student sitting near me made a noise of assent when I explained that you have to move to be part of a movement. But there was quite a bit of silence.

I turned to the assigned text: “America never was America to me, / And yet I swear this oath — / America will be!” Nottage quotes this stanza from Langston Hughes’ poem “Let America Be America Again” in the epigraph to “Sweat,” and I asked the students to consider the relationship of these lines to the play and to their own lives.

Some immediately zoomed in on Hughes’ sense of himself as an outsider in a country openly hostile to his identity. But I called their attention to the way this acknowledgement by the poet doesn’t alienate him from the collective responsibility of democratic renewal. Hughes’ resolve is beautifully expressed in lines from the poem Nottage also includes: “We, the people, must redeem / The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers. / The mountains and the endless plain — / All, all the stretch of these great green states — / And make America again!”

In entreating my drama students to do their part in rescuing our faltering democracy, I was simultaneously asking them to redeem an idea of theater as something more than sound and fury. The stage, in its highest form, is a contemplative space, where dissenting voices are free to speak, intellect and emotion can become better acquainted and hidden truths are allowed to emerge.

The choice on Nov. 6 could hardly be starker: A theater of compassionate engagement or a theater of angry bluster. Young artists, like my students, have a duty to lead the way.

Follow me @charlesmcnulty

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.