The Player: Happy 30th, ‘Super Mario Bros.,’ and thanks for the lessons big and small

It’s been almost 30 years since the release of “Super Mario Bros.,” and I still can’t get one voice out of my head. It belongs to my neighbor’s mom, and it’s scratched with nicotine.

“This is my new babysitter,” she said, pointing toward the Nintendo Entertainment System on the floor of her son’s bedroom.

She had ducked her head into the room and no doubt saw two boys transfixed by what was happening on the television screen. Each of us had just been given an NES for Christmas.

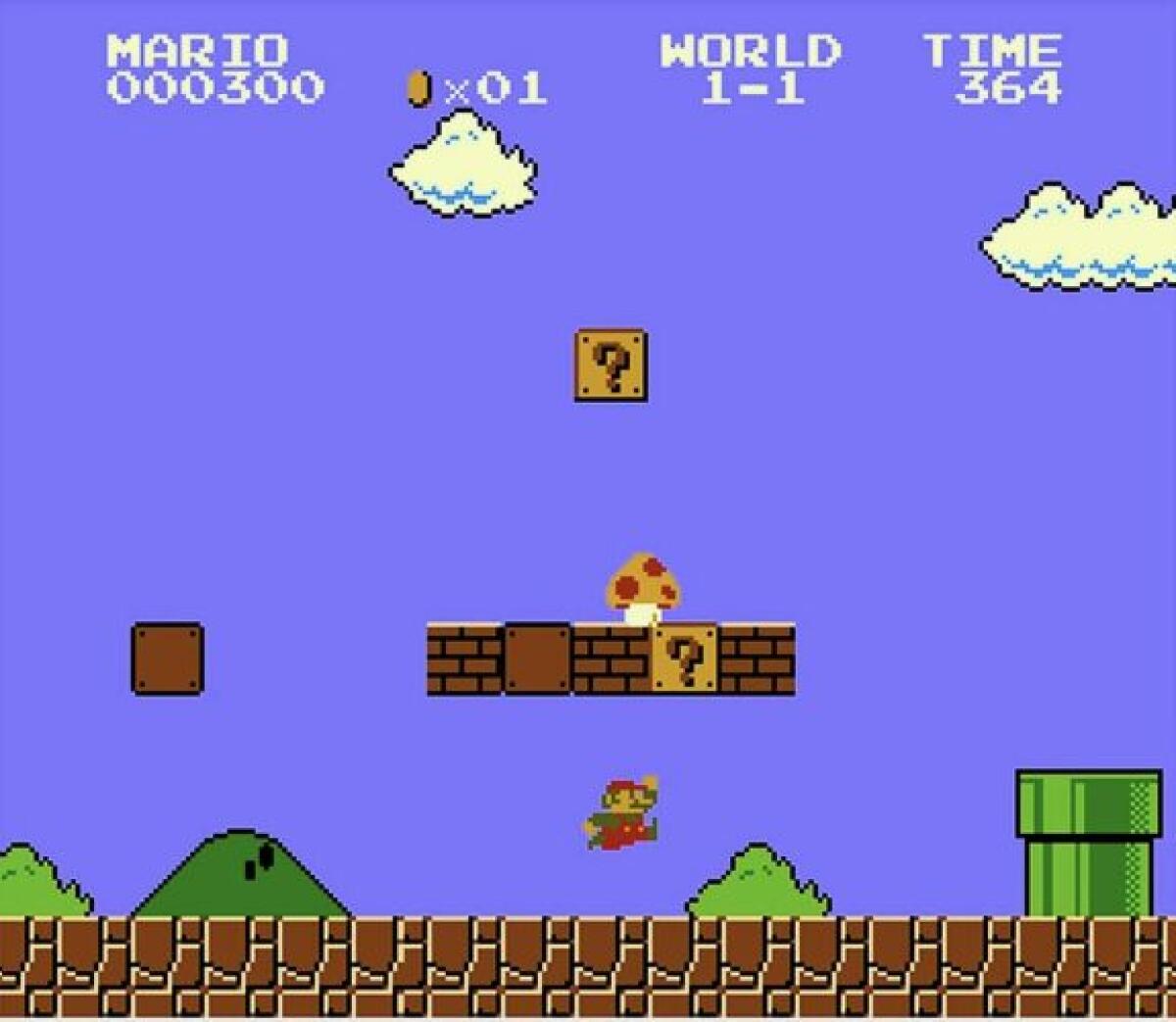

When she interrupted us, we were busy. There was a plumber who needed our guidance, giant mushroom creatures that needed our besting and angry piranha plants that needed to be avoided.

We were playing “Super Mario Bros.,” the Shigeru Miyamoto masterwork that’s celebrating its 30th anniversary this month. To commemorate — or is it hype? — the original release of the game on Sept. 13, 1985, Nintendo is releasing “Super Mario Maker,” an instructional how-to game that asks fans to create their own levels for Mario and his pals. It goes on sale Sept. 11.

Universal Studios Hollywood’s Super Nintendo World -- home to the ride Mario Kart: Bowser’s Challenge -- promises to be the most interactive theme park land ever created.

So if you’re still haunted by taking Mario underwater to battle green puffy fish, you can create a universe in which Mario never goes for a dive.

To the 7-year-old me, the worlds Mario inhabited were for a time the only ones that mattered. Why, after all, play in the snow outside when this digital universe here is offering me the ability to essentially teleport via plumbing tubes? One moment I’m in a castle. The next I’m surrounded by gold, life-giving coins! Coins!

Then my mom’s friend had to break the spell.

“This is my new babysitter.”

She wasn’t smoking at the time, but usually when I tell the story I lie and say a cigarette was dangling from her mouth. With or without the smokes, I would always see her as something of a sister-in-law from “The Simpsons.” Here she was to crush childhood dreams.

I stopped playing.

“What are you doing?” my friend yelled. Mario was now standing still on the screen. A Goomba attack was imminent. In moments, one of Mario’s lives would be gone, our progress for the past six or seven hours just a little bit erased. This post-holiday sleepover, for a few minutes at least, would be a little tense.

Here’s why I think I stopped playing that day, or at least here’s why I continue to hear her voice: When she joked that the NES was her new babysitter, I heard, whether it was her intention or not, an adult equating video games with child’s play. “This,” she was more or less saying, “is the new toy that keeps the kids occupied.”

When I was younger, I certainly couldn’t articulate the reasons, but the NES felt like something more than a mere toy. That’s not to say it didn’t also fulfill that role.

Last week, when I fired up the “Mario Maker” and once again saw the red-suited Mario standing atop crude brownish bricks and green bushes — vegetation that looks essentially like a stray strand of lettuce — a number of memories came rushing back. There were thoughts, of course, of the music, which wrapped like a bow when Mario perished, and there were also recollections of those late nights spent playing with the sound off when my parents thought I had gone to bed.

My lack of coordination always meant I was rarely a match for Bowser’s henchman, but add in a fear of being caught playing at midnight and these evening sessions were never very fruitful. My little Mario was rarely a challenge for any turtle-shelled villain, which meant I got to know the first few levels of “Super Mario Bros.” rather well.

And, via the games of Miyamoto, I learned things.

I learned a new language. Imagery and interaction were the dialect of “Super Mario Bros.,” one that often doesn’t make sense if you try to explain it with words. If you so much as touch a mushroom creature — a Goomba — you will die. But if you touch the mushroom creature by jumping on it, you will live.

I learned how to problem-solve. I learned to study patterns and movements and how to navigate a maze of moving platforms. These were visual math problems. I also learned how to cooperate with friends. After all, there were often four of us, and just two controllers. Thus, I learned how to share.

There’s more. I learned patience. Video games are difficult, and I learned how to temper frustration because my parents weren’t going to keep replacing controllers I broke in bratty anger.

So no, “Super Mario Bros.” wasn’t a babysitter. To a young, impressionable mind, it was a tutor.

I learned a lot of useless things too. I won’t pretend that video games can’t be silly, and “Super Mario Bros.” remains one of the weirdest of them all. I learned, for instance, that banging your head on a bouncy brick in the middle of the sky could yield a gold coin. I learned that sometimes plumbers can fight mushrooms with fireballs and, in a later game, raccoon tails (it all makes sense in the game). I learned that a princess, when not being kidnapped, could hover in the sky.

Thirty years later, Miyamoto is still here, still making games and still teaching me new tricks. Mario, today, can turn into a cat, and crawl up, down and around a 3-D world. Climb a tree and shake it, or avoid those Goombas by scaling a wall. Or pounce on them with claws outstretched.

Today, too, the video game medium has grown up. Some, such as “A Wolf Among Us” or “Until Dawn,” play out like interactive television shows. Others, such as “Volume” or “Papers, Please,” experiment with social issues. Some, like the new “Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain,” are designed to offer 100-plus hours of entertainment.

And then there’s Mario. He’s still a plumber. He can just now meow. Silly? Yes. Child’s play? Far from it.

Miyamoto himself has his own explanation for the enduring power of games and Mario. And no, Mario’s dad didn’t refer to his game as a time-filling babysitter. He has pretty grand ideas about the game’s ambition, actually.

“The more creative the player is, the more things that they try, the more fun the game becomes,” he said recently in Los Angeles via a translator.

Thus, said, Miyamoto, “Super Mario Bros.” is “also about the creativity of the player.”

That’s a lesson that never grows old. So happy 3-0, “Super Mario Bros.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.