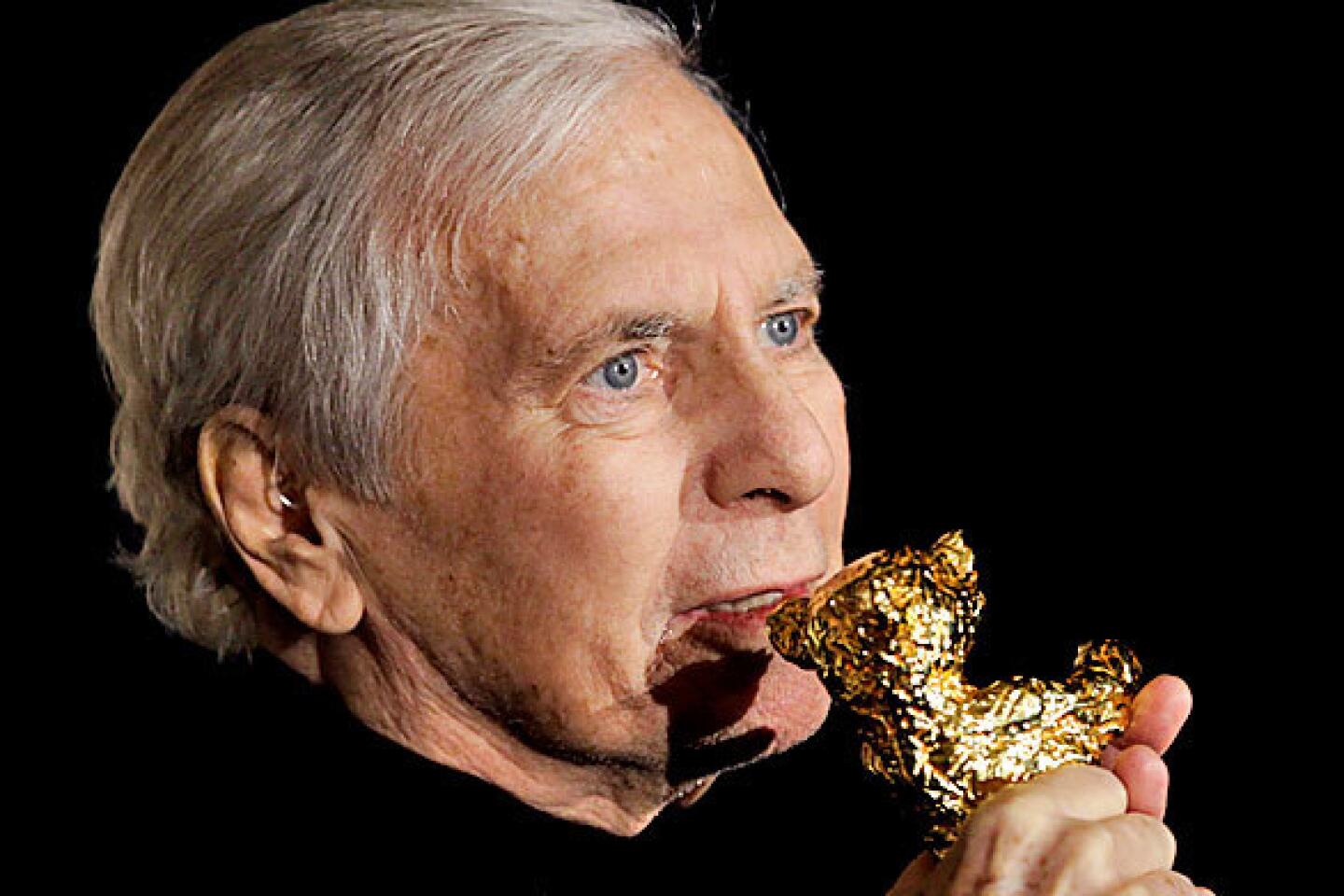

Composer Maurice Jarre spun screen magic

From the mystical overtones of “Ghost” to the primitive sounds of “Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome,” to the Russian balalaikas in “Doctor Zhivago,” composer Maurice Jarre always seemed to find the right signature for every film he scored. And unlike so many of today’s thundering but essentially interchangeable big-orchestra-plus-electronics scores, the voice of a Maurice Jarre film was always uniquely his own.

Jarre, who died Saturday at age 84, suggested exotic locales with instruments unique to the region being portrayed. He subtly conveyed changes in tone, depending on the story being told -- and, yes, he often came up with a memorable melody that kept people humming as they left the theater.

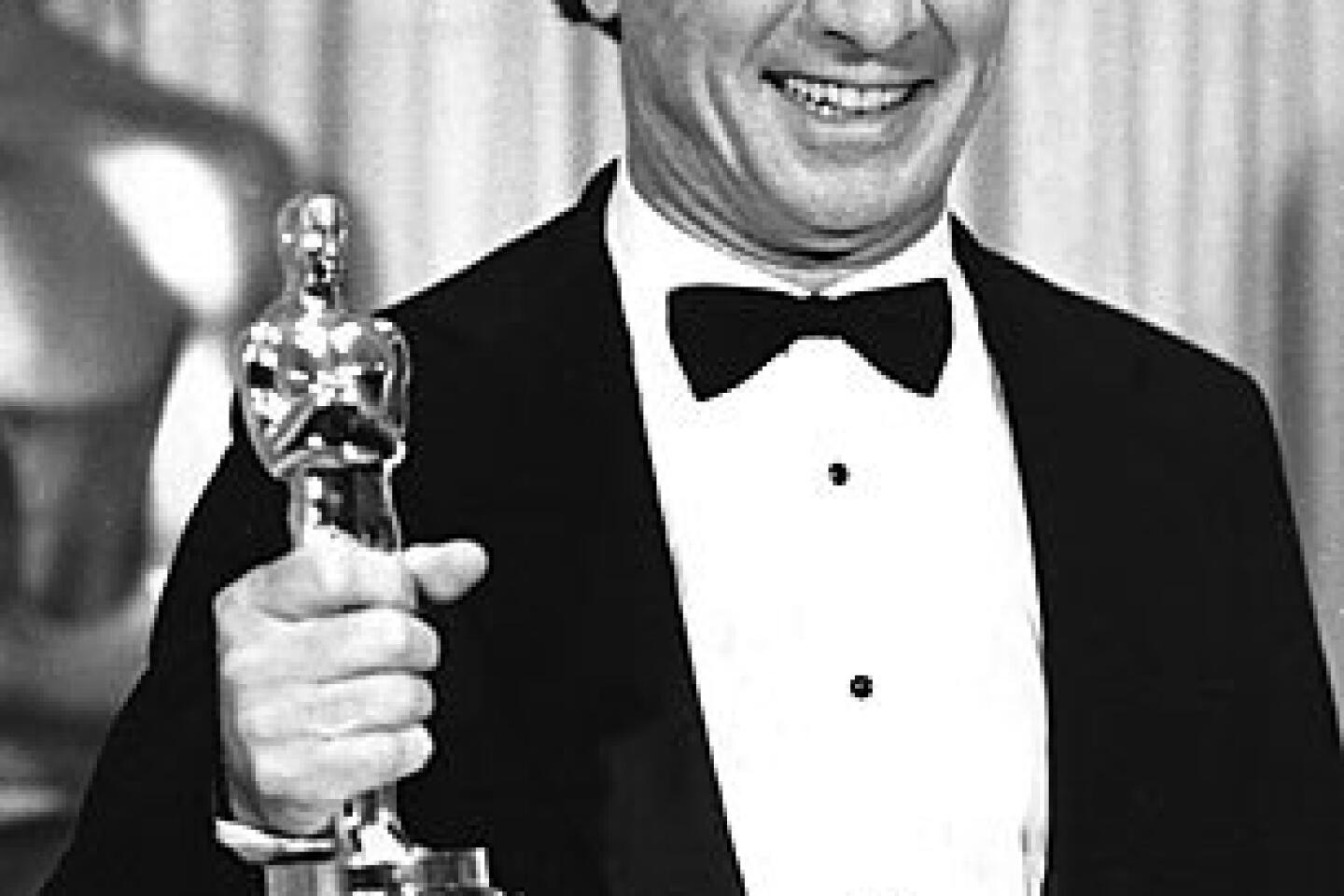

Jarre will always be best-known for the music he wrote for “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Doctor Zhivago,” two of his four films for English director David Lean that won him two of his three Oscars. In “Lawrence,” Jarre’s music evoked the grandeur of the Arabian desert, a sense of the English military presence in the Middle East and, most of all, the mysterious figure of T.E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole).

“Lara’s Theme” from “Zhivago” -- Jarre’s most popular tune, which helped drive the soundtrack to No. 1 on the Billboard charts in 1966 -- isn’t particularly Russian in character. It was designed to convey the love between Yuri (Omar Sharif) and Lara (Julie Christie) that transcended time and place. Lost in all the attention to “Lara’s Theme” is the fact that Jarre’s complete score is filled with Russian flavor, not only in the melodies but also in the 24 balalaikas and 40-man chorus that augmented the MGM orchestra in Culver City.

Jarre, who studied ethnomusicology at the Paris Conservatory and was a percussionist before becoming a composer, loved using ethnic instruments whenever the project called for a unique sound indigenous to the locale. For John Huston’s “The Man Who Would Be King,” set in far-off Kafiristan, Jarre hired Indian musicians to perform on the sarangi and sarod, Indian lutes; for Volker Schlöndorff’s “The Tin Drum,” a Slovakian shepherd’s flute called a fujara seemed right.

These were the colors that Jarre added to his palette, the instruments that executed his themes and variations that were specific to each project. He could be daring in his conceptual approach to music for films. For example, his music for Franco Zeffirelli’s “Jesus of Nazareth” eschewed heavenly choir cliches in favor of a warm and intimate sound reflecting the personal story being told. For Peter Weir’s “Witness,” a film set in Pennsylvania’s Amish country, he risked controversy by writing only for synthesizers. And those are just a few of the more than 170 films and TV projects, spanning nearly 50 years, for which Jarre supplied the music.

The best film composers don’t just write music for movies. They participate in a kind of alchemy whereby they absorb the ideas and imagery of a film, then re-imagine it as an audio-visual whole. Their music conveys not just pictures but also emotions, heightening the drama in ways that even the director may not have imagined.

Jarre was one of a handful of film composers who could pull off that kind of screen magic. It’s sad to think that his unique voice, one of few remaining in Hollywood, has been silenced.

Jon Burlingame is author of “Sound and Vision: 60 Years of Motion Picture Soundtracks.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.