395: the number of women who have contacted The Times with allegations of sexual harassment against James Toback

Last week, the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office announced that it was reviewing five investigations into accusations of sexual misconduct against filmmaker James Toback.

Coincidentally, it was the first week in more than three months that I hadn’t heard from a woman alleging that Toback had harassed her — or worse.

Why this is noteworthy requires a little back story.

Shortly after accounts of Harvey Weinstein’s decades of alleged sexual harassment broke in the New York Times and the New Yorker, a filmmaker friend contacted me, saying he had spoken to an actress who had been similarly harassed by Toback. I spoke to her the next day, but she was afraid to be publicly identified. I also contacted five women who had named Toback on Twitter, using the #MeToo hashtag. Within days, I had spoken with 38 women whose stories we corroborated, 31 of whom were willing to go on the record. (Toback denied the allegations.)

Minutes after the investigation was published, other women began emailing and phoning me with similar stories, many putting “call me No. 39” in the email subject line.

Since that initial story ran in late October, 357 women have contacted me about Toback, sharing stories of the writer-director approaching them on the streets of Manhattan and Los Angeles, on trains and airplanes. In most of these accounts, he told them that he wanted to cast them in a movie, which often led to a range of unwanted sexual advances and actions. (Toback has also denied all of the subsequent allegations on multiple occasions.)

I’ve spoken with or emailed every woman who reached out. Most of the 395 women offered highly detailed accounts, and some shared physical evidence — journal entries, photographs of plane tickets, receipts, scraps of paper with Toback’s writing.

Some were matter-of-fact, some were triumphant, some were still ashamed, some were angry — and many remain so, since many incidents involving Toback, occurring over the course of four decades, fall outside the statute of limitations. Nearly all of them expressed some measure of relief. After years of being told to keep quiet, accept things as they are (or find a new line of work), these women decided it was time to break their silence, seize control of the narrative and let their voices be heard.

And, for many, speaking out is just the opening salvo in what they hope will be systemic change in every workplace, not just the entertainment industry.

As we enter awards season, their narrative has become our narrative. Toback and Weinstein were not alone in their behavior. Since October, dozens of high-profile men — politicians, judges, media and entertainment figures — have been accused of sexual harassment, assault and even rape. Reputations were destroyed; many lost their livelihoods.

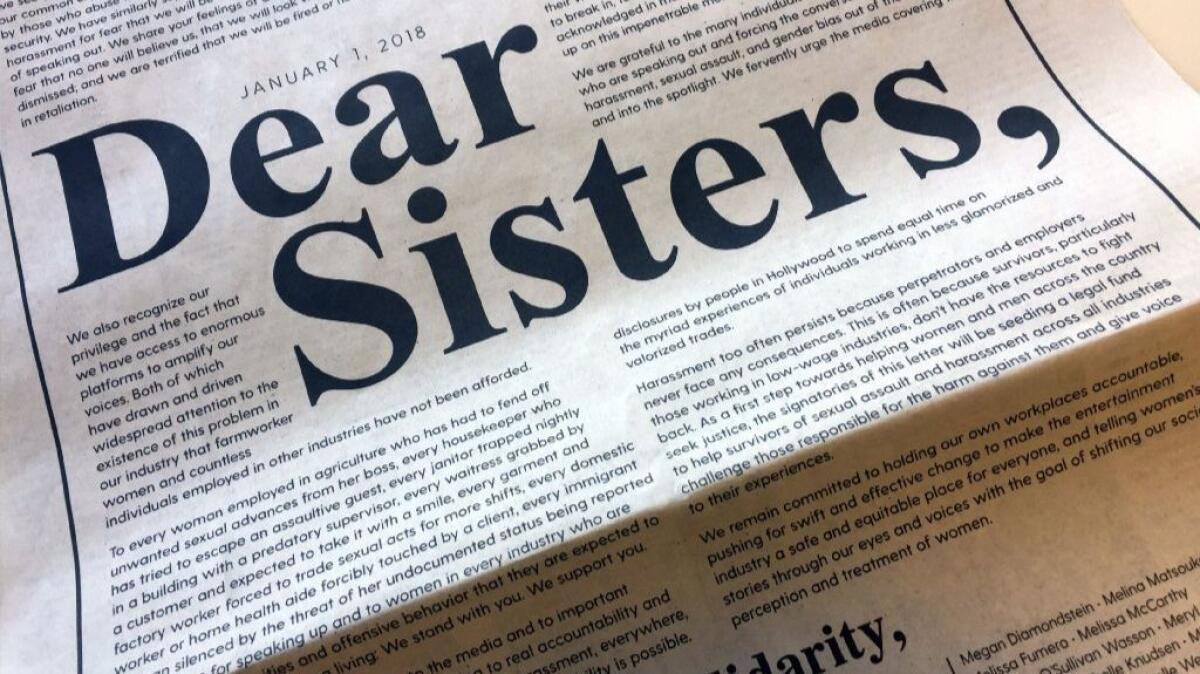

Meanwhile, the #MeToo movement became #TimesUp. On Monday, more than 300 powerful Hollywood women, including Reese Witherspoon, Shonda Rhimes and Kerry Washington, established an initiative to fight sexual harassment that includes a legal defense fund, a gender parity push and a request that all women walking the red carpet at Sunday’s Golden Globes ceremony wear black.

The personal became political and, because it’s Hollywood, well-publicized.

For the women united by their encounters with Toback, these movements are welcome and a long time coming.

“There’s long been a need to create a way for women in all workplaces to report harassment,” said filmmaker Ambika Leigh, who says she encountered rampant harassment early in her acting career, including an incident with Toback. “Because right now, even with all that’s happened in recent weeks, there’s still a lot of fear and uncertainty.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

Many of the women who contacted me about Toback said that dredging up these memories left them feeling vulnerable, but that the process was cathartic. And seeing other women declare their truth has empowered others to do the same.

“Courage begets courage,” said actress Dani Alvarado, who said she had a series of encounters with Toback in 2011. “After years of feeling like there would never be any repercussions, it’s been amazing to see the pendulum swing in a different direction.”

“When you have 38 women saying the same thing, suddenly you feel like what happened to you actually means something,” noted Kandiss Edmundson, who said she met Toback in 2001 when she was an aspiring actress. “It proves a pattern, which makes me feel like my story is valid. It’s real. No one can talk me out of the pain of it or downplay it or make me feel stupid or responsible or naive.”

“Shame keeps you silent,” added singer-actress Christine Hudman, who, like the others, said she had an encounter with Toback that was framed as an audition but turned sexual. “I’m not quite sure how to articulate what he took from me that day, but by saying this, I feel that I’m taking something back.”

(The Times reviewed evidence supporting the accounts of the women mentioned in this story, interviewing relatives and friends and examining records contemporaneous with the incidents.)

Many women began working on that process years before publicly talking about their encounters with Toback. Miranda Calderon says she used Toback’s crude come-ons as inspiration to write a 2012 short film, “Alegra & Jim,” in which she plays a young actress trying to figure out the difference between artistic exploration and sexual harassment.

“I wanted to look at the responsibility that men in power have in that kind of situation and the emphasis that art places on boundary-breaking, and how that’s sometimes used to prey on women,” Calderon said. “I don’t think creative people should be immune from ethical conduct.

“Making my own work was in some way an antidote to the powerlessness and neediness that actors often feel, that young women often feel,” she added.

Alvarado premiered her own short film about industry sexual harassment, “Lost Beneath the Stars,” based in part on an encounter with Toback, at the Warsaw Film Festival in October. The day after she returned to Los Angeles from Poland, the Toback story broke in The Times. The timing, she said, was “shocking and absurd.”

Alvarado wrote the movie with her actress friend Claire Bermingham as a form of release and expression, and she says a small part of her hoped Toback would see it.

“It was so wonderfully ironic that he said he wanted to write a role for me and I ended up writing a role for him,” Alvarado said. “To use his words, words he apparently spoke to so many other women, I hope I ‘captured his essence.’ ”

Lori Seliger wrote and produced a play, “James You’re Sweet,” that was performed at New York’s Tribeca Lab in 1992. Tamar Kummel titled her 2005 play “The Seduction” and dedicated it to Toback. (“I find it quite a statement about being an actor, that it never occurred to me to call the police” after her incident with Toback, she said.) Actress and comedian Inna Swinton wrote and performed what she calls her Toback-inspired play, “The Part,” in New York in 2003.

“By owning the story and rewriting it as a comedy, it helped me deal with what happened,” Swinton said. “That was my way of processing a situation that I remembered being so sad, that this man was out there preying on women’s dreams.”

Most women didn’t use an artistic outlet to process what happened to them. Many said they hadn’t spoken of their encounters with Toback since they occurred years earlier. Some hadn’t told their longtime spouses until after the story ran. The trauma of the experiences ran too deep.

“It was the one secret I never shared about myself with my husband or anyone else,” said Sarah MacKay, who was an aspiring actress studying musical theater at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy in New York when she met Toback in 2004, adding that, because she blamed herself, she felt too much anger and shame to talk about what happened to her. Hearing others do so changed that.

“I started to feel an overwhelming sense of relief, validation and encouragement in knowing I wasn’t alone,” MacKay said. “And, for the first time ever, feeling that it wasn’t my fault that I’d been assaulted.”

“Things I had previously kept to myself, weathered like some sick rite of passage, I started to share in this new public conversation about sexual harassment,” said Amy Korb, who, like so many other women, said she had an audition experience with Toback turn sexual. “The worst part about it is that it almost — almost — felt normal. Now I understand my dreams are what made me vulnerable.”

Several women related encounters with Toback that happened when they were underage. Jaime Lyn Beatty said she met him at a Tribeca Film Festival screening of “The Outsider,” a documentary about Toback and the making of his 2004 film “When Will I Be Loved.” She approached him afterward, expressing an interest in acting. He invited her to dinner, during which he probed Beatty with questions that were sexual in nature. She was 16.

“At the time, I just normalized it, like, ‘This is just another Hollywood eccentric,’ ” said Beatty, who became an actress. “I don’t think I really processed what happened until just recently, when the climate changed and I realized that what I had kept private as a singular experience was in fact a very universal experience shared by a sisterhood of women.”

Women accusing other men — Weinstein, producer Brett Ratner, actor Dustin Hoffman — voiced similar feelings in op-ed pieces, on social media and in private messages to each other. “Women found me through Twitter, Facebook and mutual friends to share their Hoffman stories,” Anna Graham Hunter wrote in a Times piece about the aftermath of her initial essay accusing the actor of harassment.

The women bound by shared experiences with Toback and others have created private groups on Facebook and Twitter, places they can form friendships, share stories and provide one another with emotional support.

“It started with this one perpetrator, but it has widened to become a place to discuss this problem on a much wider scale,” Leigh said. “To speak about these awful experiences is healing.

“What’s even more healing is the sense that people are finally listening.”

Twitter: @glennwhipp

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.