From the Archives: William Goldman knows they don’t know

- Share via

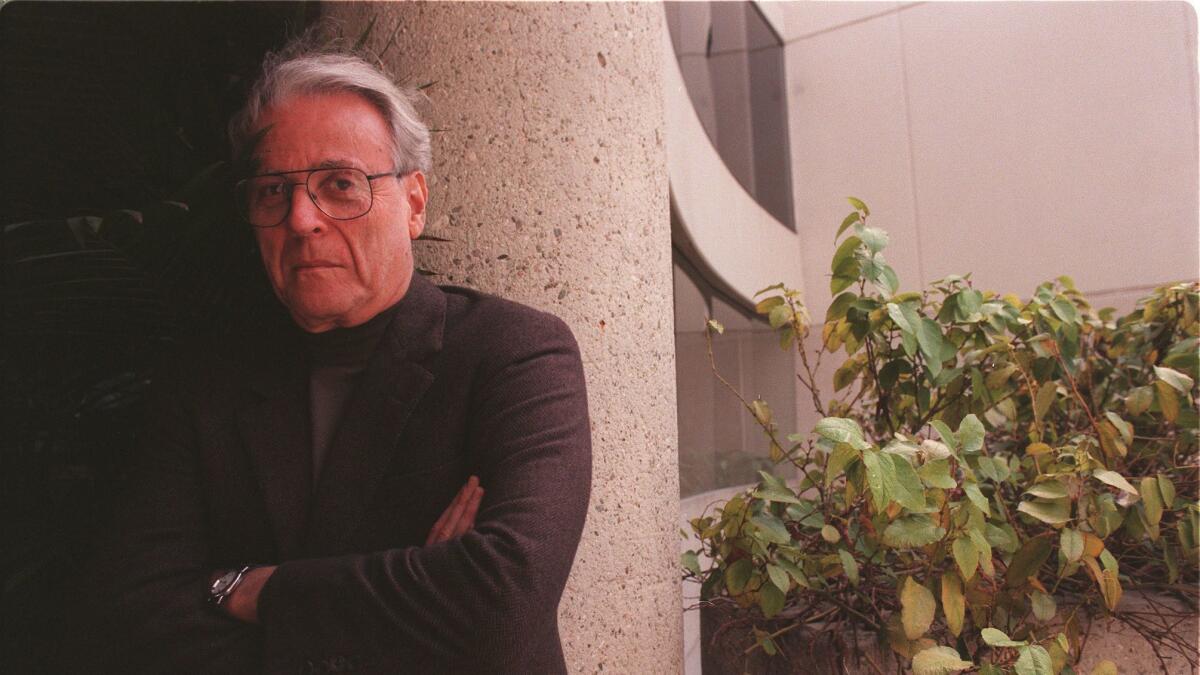

Editors note: Screenwriter William Goldman died Friday at 87 at his home in Manhattan of complications from colon cancer and pneumonia, said his daughter Jenny Goldman. The story below is an archived profile of Goldman, which ran in The Times on April 2, 2000, and details his book “Which Lie Did I Tell?” which gives the latest lowdown on Hollywood movie-making.

With his friend John Cleese of “Monty Python” fame seated at his side onstage at the Writers Guild Theater in Beverly Hills, William Goldman looked out on hundreds of fellow screenwriters one recent evening and had a confession to make.

Goldman, who won Academy Awards for writing “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and “All the President’s Men,” said he had skipped seventh grade, “which is the grade we learn grammar.”

“Now you know why I write mostly dialogue,” he quipped, as laughter rippled through the audience.

Goldman’s appearance marked the end of a hectic 12-hour publicity blitz through Los Angeles to hype his chatty new book about Hollywood and the movies titled “Which Lie Did I Tell?: More Adventures in the Screen Trade” (Pantheon Books).

The book takes its title from a question asked of Goldman one day in a Las Vegas hotel room by a blowhard producer who was on the phone promoting his latest projects, “spouting inaccurate grosses, potential star castings, stuff like that.” Suddenly, Goldman writes, the producer put his hand over the mouthpiece and said, “Bill, Bill, Which lie did I tell?

In 1983, Goldman had Tinseltown buzzing when his tell-all bestseller, “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” hit the shelves and his now-famous phrase, “Nobody knows anything,” entered the film world’s lexicon. That phrase, he believes, is as valid today as ever.

“Nobody has the least idea, I believe, what will work and what won’t work for audiences,” Goldman said in an interview before going onstage. “Even the most successful director of all time, Mr. Spielberg — look what happened to ‘Amistad’? Do you think he thought it was going to bomb? No! They don’t know.”

Goldman holds a unique place in Hollywood — a veritable “Mr. Outside” and “Mr. Inside.” Not only does he work with many of the industry’s power players, but he is also given wide latitude to launch literary Scuds at the very same industry that pays his bills.

“The reason he is allowed this is because he comes from a place of success,” said screenwriter Scott Frank (“Out of Sight,” “Get Shorty”), who looks upon Goldman as his writing mentor. “Unlike most people in Hollywood, he is not bitter. He is only saying what we all wish we had the guts to say.”

Frank said that Goldman is one of the few screenwriters who understands both cinematic storytelling and telling a story from character. “One of the things that Bill is known for is that he constantly surprises you — not only within the narrative, but within the scene.”

Yes, Goldman will venture out of New York (he loves his Knicks) to take meetings at the usual L.A. watering holes, but if you blink twice, you might miss him.

“I don’t come to L.A. often, and I don’t stay long,” he said. “I get very edgy out here. I’m edgy anyway. Usually, if the meeting is in the morning, I come out the day before. If it’s in the afternoon, I’ll come out the morning of and I usually am gone the next day. ... Here’s the deal: I’m the only living American male who admits to being a terrible driver. I hate to drive. I have no sense of direction whatsoever and it’s hateful, so I just don’t do it.”

In his new book, Goldman offers not only a primer for would-be screenwriters — including an original screenplay he wrote for the book that he allows some of today’s top screenwriters to analyze, doctor or destroy — but also sprinkles the book with amusing, if sometimes pointless, tidbits he has collected over the years, such as:

* Jumping into the pool at the Hotel du Cap during the Cannes Film Festival to verify the true height of action superstar Sylvester Stallone. “Sixty-seven inches, dripping wet.”

* Watching an exhausted Val Kilmer one day flub his lines so often on the African set of “The Ghost and the Darkness” that producer and co-star Michael Douglas pulled him aside and said: Do you want a career like Eric Roberts? Do you want a career like Mickey Rourke? Well, you can have that if you don’t shape up.

* Informing us that one of the great scenes in the 1994 film “Maverick” involved Linda Hunt as the Magician. Don’t remember it? That’s because it was cut out.

* Writing a Chevy Chase project called “Memoirs of an Invisible Man” and having the former “Saturday Night Live” star ask if the script could explore the loneliness of invisibility. Which triggered this reaction by Goldman: “AAAARRRGHHHH!”

Goldman also wants everyone to know that he did not — repeat not — write the 1997 film “Good Will Hunting.”

“That one drives me mad,” he said. “People can’t believe Matt Damon and Ben Affleck wrote ‘Good Will Hunting,’ and it’s on the Net that I wrote it. I’ve written over and over, I did not write it. I met with them for one day. Their script had such wonderful stuff in it.”

At 68, Goldman says it shouldn’t surprise anyone that he still works in Hollywood while dishing dirt about the movies.

“I was at Cannes a couple of years ago, and I was doing interviews with the European press, and they asked me, ‘How can you say the things you say and stay in the business?’ ” Goldman recalled. “And, I said, ‘I’m a screenwriter. You don’t know how low that is.’ ”

Goldman has opinions.

His favorite films of the last decade? “Unforgiven,” “Babe,” “Fargo,” “The Shawshank Redemption,” “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape,” “Four Weddings and a Funeral” and the documentary “Hoop Dreams.” And, he adds, perhaps “There’s Something About Mary.”

His favorite screenwriters? Ingmar Bergman and Billy Wilder. “They both told stories that nobody else was telling, and I found them fascinating.”

But he is certainly not shy about hurling barbs.

Take the Oscar-nominated police drama “L.A. Confidential.” Goldman shakes his head at the climactic scene in which James Cromwell blasts away at everybody.

“He’s whacked Kevin Spacey. He has killed everyone. And he misses [Guy Pearce]! And Russell Crowe gets to spend his life with Kim Basinger, who miraculously is no longer a whore? For me, that’s Hollywood horse... and I think damaging because that movie was not a hit.”

He also loved the first hour of “Three Kings,” when the American GIs are plotting to steal a cache of gold that Iraq has stolen from Kuwait. But then, Goldman said, the movie loses all credibility when George Clooney suddenly tells his cohorts to stop what they are doing and save all these poor Iraqis.

In the book, Goldman pays homage to his favorite movie sequences. He calls the famous crop-dusting chase scene of Cary Grant in “North by Northwest” one of the best action sequences ever filmed, and not because of Alfred Hitchcock’s direction, but because of how it was written by Ernest Lehman. He also tosses bouquets at Meg Ryan’s fake orgasm scene in “When Harry Met Sally ...” and Ben Stiller’s zipper scene in “There’s Something About Mary.”

Hollywood has changed dramatically since Goldman wrote “Adventures in the Screen Trade.” When that book came out, he noted, the biggest movie stars were Bill Murray, Eddie Murphy and Sylvester Stallone.

“They were the Cruise, Carrey and Hanks of their day,” he said. “It passed. Eddie Murphy made it back, Stallone’s trying to, and Bill Murray, I don’t know if he is interested.”

Like everyone in Hollywood, Goldman is shocked that the average cost of producing a studio film today soars above $50 million, with major stars pulling down $20 million a picture, plus lucrative perks.

“But I don’t blame the stars,” he said. “I don’t want a star to say, ‘No, no, don’t give me $20 million, give me $3 million.’ That’s not the star’s job.”

Studios pay these enormous sums, he said, because they don’t really know what will work, so they hedge their bets by paying a star who is a proven box-office draw the big bucks. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

“I predict, having not seen a foot of film, that the biggest movie of this year is going to be a movie called ‘Gladiator,’ ” Goldman said. “I’m just sensing that there hasn’t been one of those great, big Roman movies done with contemporary special effects. ... But I’m the same guy who, if I was a studio head, would have made ‘King David’ with Richard Gere, which was a wild disaster. I still think that if a director who can do size would do a biblical movie it would clean up.”

Goldman has been around Hollywood long enough to know that a successful career lasts only as long as your last hit.

Two decades ago, he was sitting on top of the world. Between 1973 and 1978, Goldman wrote three novels (“The Princess Bride,” “Marathon Man” and “Magic”) and six movies (“The Great Waldo Pepper,” “The Stepford Wives,” “All the President’s Men,” “Marathon Man,” “A Bridge Too Far” and “Magic”).

Then the phone stopped ringing. The failure to get several movie projects off the ground left him ostracized in Hollywood. From 1980 to 1985, no one called with anything resembling a job offer. In the book, he calls these “The Leper Years.”

Slouching on a couch in the theater’s green room and staring at the ceiling, Goldman said he was just glad he lived in New York City during that bleak period and not Los Angeles.

“Oh, my God, to come to the Writers Guild Theater and have people turn away — I would have become a total hermit!” he said. “This is a very tough town, this is a very insecure town, and a very insecure business, because we don’t know what will work. I don’t believe people in the insurance business are nervous. I think people in the movie business are nervous because we’re just all on a crapshoot.”

Goldman’s long climb back is charted in his book, which is sprinkled with anecdotes about what it was like working with Eastwood, Douglas, Mel Gibson, Richard Donner, Rob Reiner and other major Hollywood players.

Goldman, it should be noted, is not only famous for coining the phrase “Nobody knows anything.” He also came up with one of the great lines in American politics — “Follow the money” — which instantly defined the Watergate scandal.

The phrase was uttered by the shadowy figure “Deep Throat” to Robert Redford in the film “All the President’s Men.” Goldman said he actually thought it came from Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Watergate book but later discovered it hadn’t.

Goldman continues to write regularly. He co-wrote last year’s John Travolta movie “The General’s Daughter,” and other recent writing credits include Eastwood’s “Absolute Power” and the Stephen King thriller “Misery” (Goldman wanted the victim’s feet lopped off by Kathy Bates’ character, as King wrote it, but he was overruled by the producers and now admits the revision made for a better movie).

While he still remains a much sought-after “script doctor,” those hired guns who are paid fabulous sums to rescue a screenplay or give it a final polish, Goldman recently finished a screenplay adaptation for Castle Rock Entertainment based on the King novel “Hearts in Atlantis.” Meanwhile, he has written 75 pages on a sequel to his novel “The Princess Bride” and has plans to come out with a large picture book titled “The Basic Literature, or All the Movies You Need to Know to Know the Movies.”

“It will be divided up into decades, the greatest movies of all time, the Oscars, stars, directors, who’s overrated, who’s underrated, what do you have to know? What French movies do you have to know — very few, very few. What Spanish movies — a couple. This is basic. It’s all my opinion. It’s the end. It’s the last shoot. I’ll be 70 when it comes out.”

While many screenwriters have ventured into directing, Goldman said being a director holds no interest for him.

“By the time I finish a script, going over it and over it, I almost know it by heart,” he said. “The idea of then spending another year on it never appealed to me.”

On this night at the Writers Guild Theater, with Cleese asking him questions onstage, Goldman dispensed a variety of opinions — some witty, some serious — but the screenwriters present might have been surprised to discover he is really insecure about his talent.

“We did not become writers to be Jacqueline Susann,” Goldman told them. “We became writers, in my case, because of Somerset Maugham, because of Chekhov, because of all those guys that, when you go in your pit [to write], you know you’re not as good as they are. And so your whole life you are faced with the failure of your own inadequacies.”

Cleese, ever the humorist, looked over at Goldman and remarked dryly: “It’s particular in your own case.”

As laughter erupted, Goldman replied, “It’s 100% true in my own case. That’s why I like to get on with something else, so I’m not going to get caught.”

“My,” Cleese said with mock surprise, “it’s a miracle that you’re here tonight.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.