Appreciation: Gregg Allman was the voice and face of Southern rock

Call it the big bang of Southern rock: the convergence of forces that led two brothers, Duane and Gregg Allman, to convene in Jacksonville, Fla., on March 26, 1969, for a jam session that would beget the Allman Brothers Band.

Even further, call it a defining moment of the jam band era, because what happened that day helped set the foundation for a uniquely American, and enduring, musical movement.

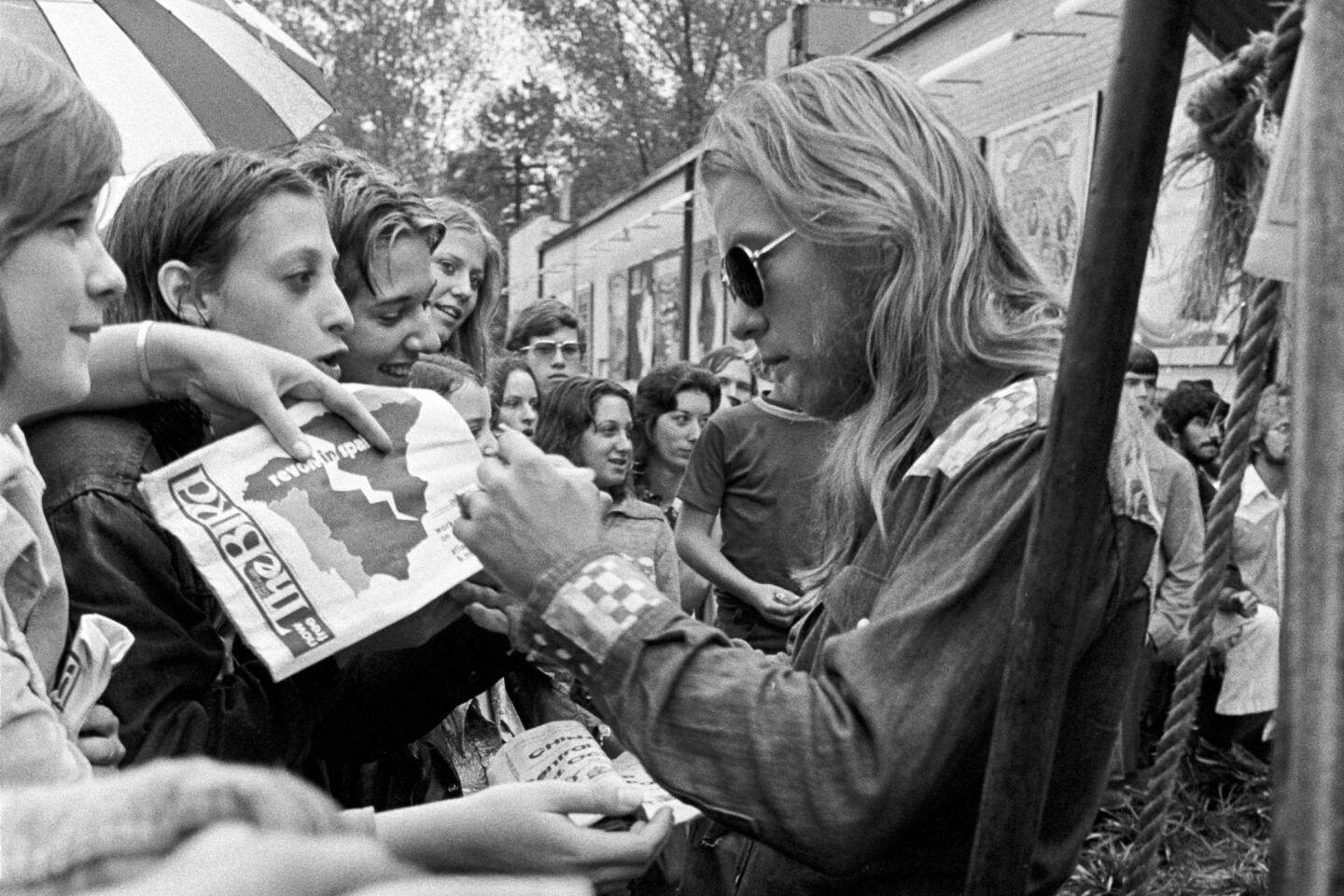

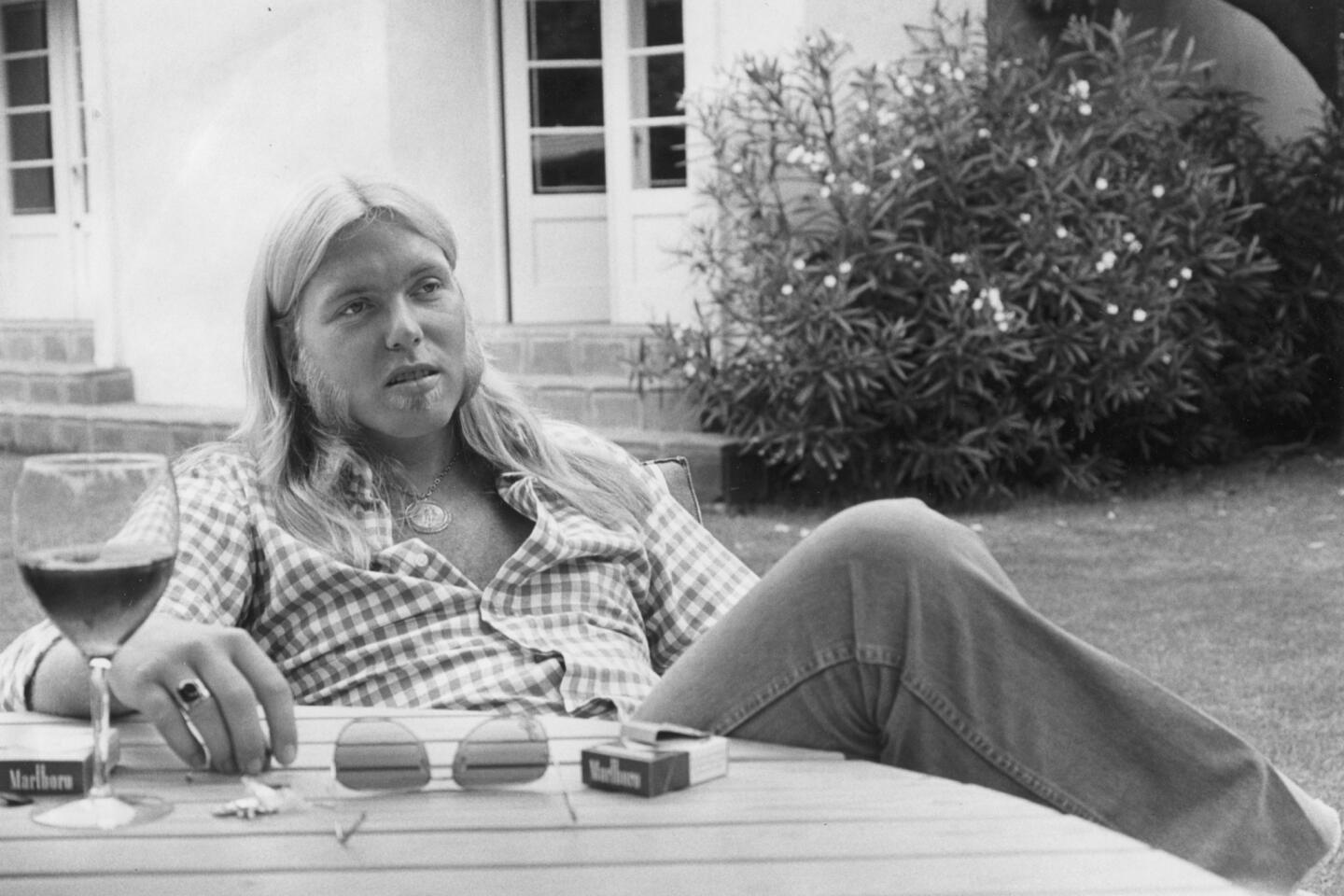

Gregg Allman, who died Saturday at age 69, served as a primary voice and face of that movement, and he helped carry the Allmans’ music to the masses through songs including the epic “Whipping Post,” “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa.” He became a gossip column staple through his relationship with Cher, wrestled with various addictions and lived much of his life on the road playing music.

On that Wednesday in 1969, though, Gregg was hardly a hot property, and he arrived at drummer Butch Trucks’ house to face the skepticism. Gregg had been living in Los Angeles, frustrated and signed to a fruitless deal with Liberty Records. His older brother Duane, who would die in a motorcycle crash in 1971, had his own label issues, and retreated to the Allmans’ hometown to start anew with his own band.

“It was real tense in there. You could have cut it with a knife,” Gregg wrote of that first rehearsal in his 2012 autobiography (with Alan Light), “My Cross to Bear.”

“Thank God they had a real good sound system set up, so when I started singing, they could hear me, and everything came together at that moment.”

What converged mixed rock, blues, country and jazz. It was twangy but not folky like the Grateful Dead. The Allmans’ music was tightly wound and urgent where the Dead’s was laid back, with extended solo and improvised moments that reveled in structural freedom.

How much freedom? The Allmans’ Fillmore East version of “Whipping Post” earned heavy rotation on FM radio — despite it being longer than 22 minutes.

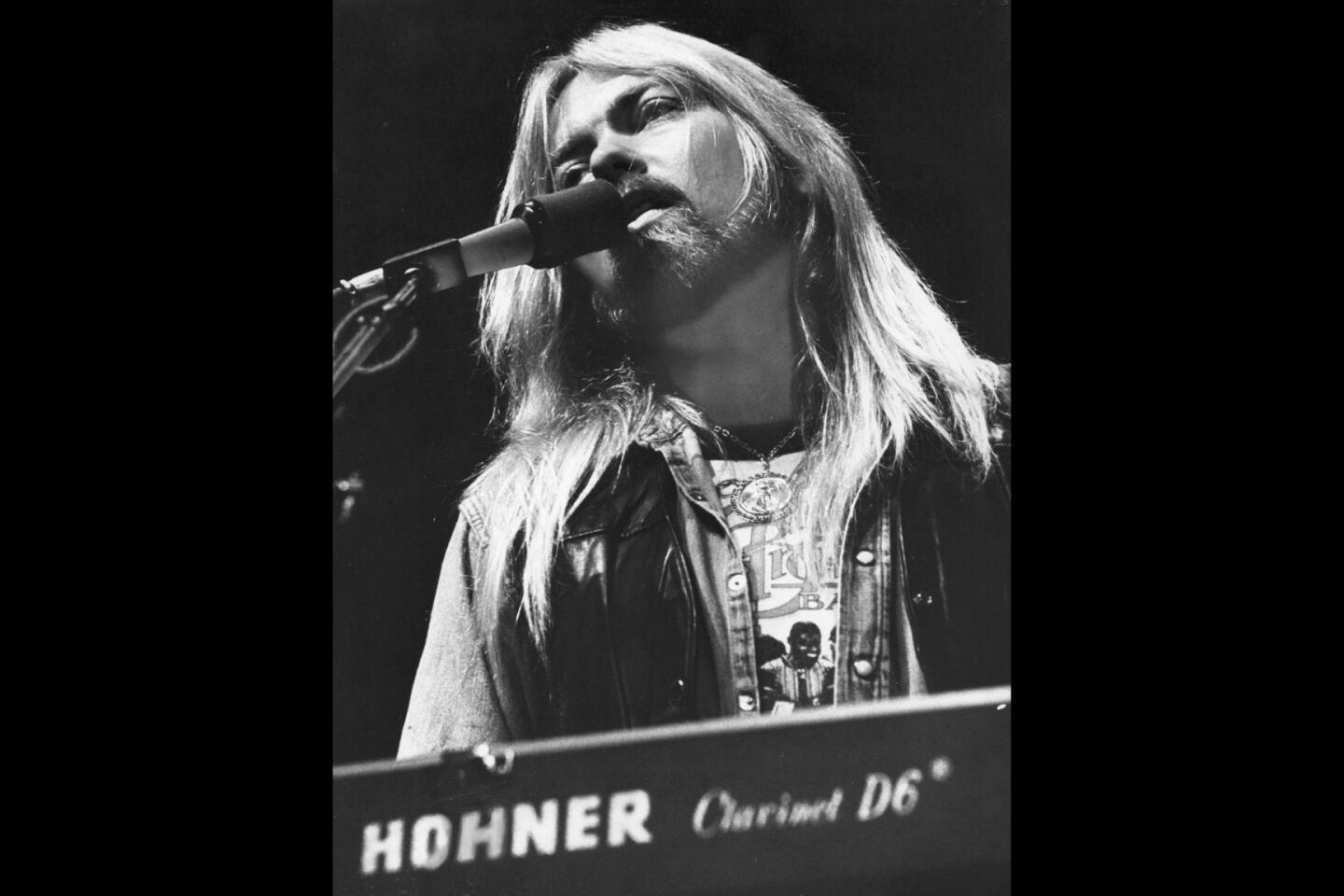

Through it all, Allman’s cigarette-strained voice, raspy and soulful, delivered originals and blues standards, a stew of influences transforming songs such as Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues” and T-Bone Walker’s “Stormy Monday” into rollicking rockers featuring the dueling guitar action of Duane Allman and Dickey Betts. The double-drumming of Trucks and Jai Johanny Johanson added rhythmic heft.

Gregg played organ and sang, uniting the competing textures under the guidance of spare keyboard chords, wicked solos and his husky voice.

Hailed as classics now, the band’s first few albums — with Gregg responsible for most of the songwriting -- pleased the critics but barely made a dent on the charts. Although the band was incendiary live, its studio albums didn’t pack as much punch.

Those who want punch, though, should blast the group’s breakout album, “At Fillmore East.” Recorded across a number of nights at the New York outpost of Bill Graham’s club, the four sides of the double album featured a mere seven songs.

Within those few songs, however, were mountainous improvised moments made possible by a well-practiced band that had been touring for nearly two years straight.

To say they jammed is an understatement. Songs such as “You Don’t Love Me” and “Hot ’Lanta” seemed to spring from the gate at full sprint and carried momentum without any noodling and little self-indulgence.

As a lyricist, Allman was hardly a genius, and may have relied too much on blues tropes about being short on money and time, about hard love and messy rejection. In “Whipping Post,” which he wrote, the singer bemoans losing a lover who “took all my money, wrecks my new car/ Now she’s with one of my good time buddies/ They’re drinkin’ in some cross-town bar.”

Despite the whipping post’s symbolism in the antebellum South, the song makes no reference to its use as a tool of slavery.

A sin of omission, perhaps, but by its very nature the mostly white Southern rock movement could be a minefield, with some acts and their fans celebrating regional heritage by embracing the Confederate flag.

Yet Gregg Allman, who recorded six solo albums during his career, strongly rejected symbols of Southern pride that called for a return of the Confederacy, doing so as he celebrated the blues and soul music that inspired him.

“I was taught how to play music by these very, very kind older black men,” he said in a 2015 interview with Radio.com. “My best friend in the world is a black man. If people are gonna look at that flag and think of it as representing slavery, then I say burn every one of them.”

For tips, records, snapshots and stories on Los Angeles music culture, follow Randall Roberts on Twitter and Instagram: @liledit. Email: randall.roberts@latimes.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.