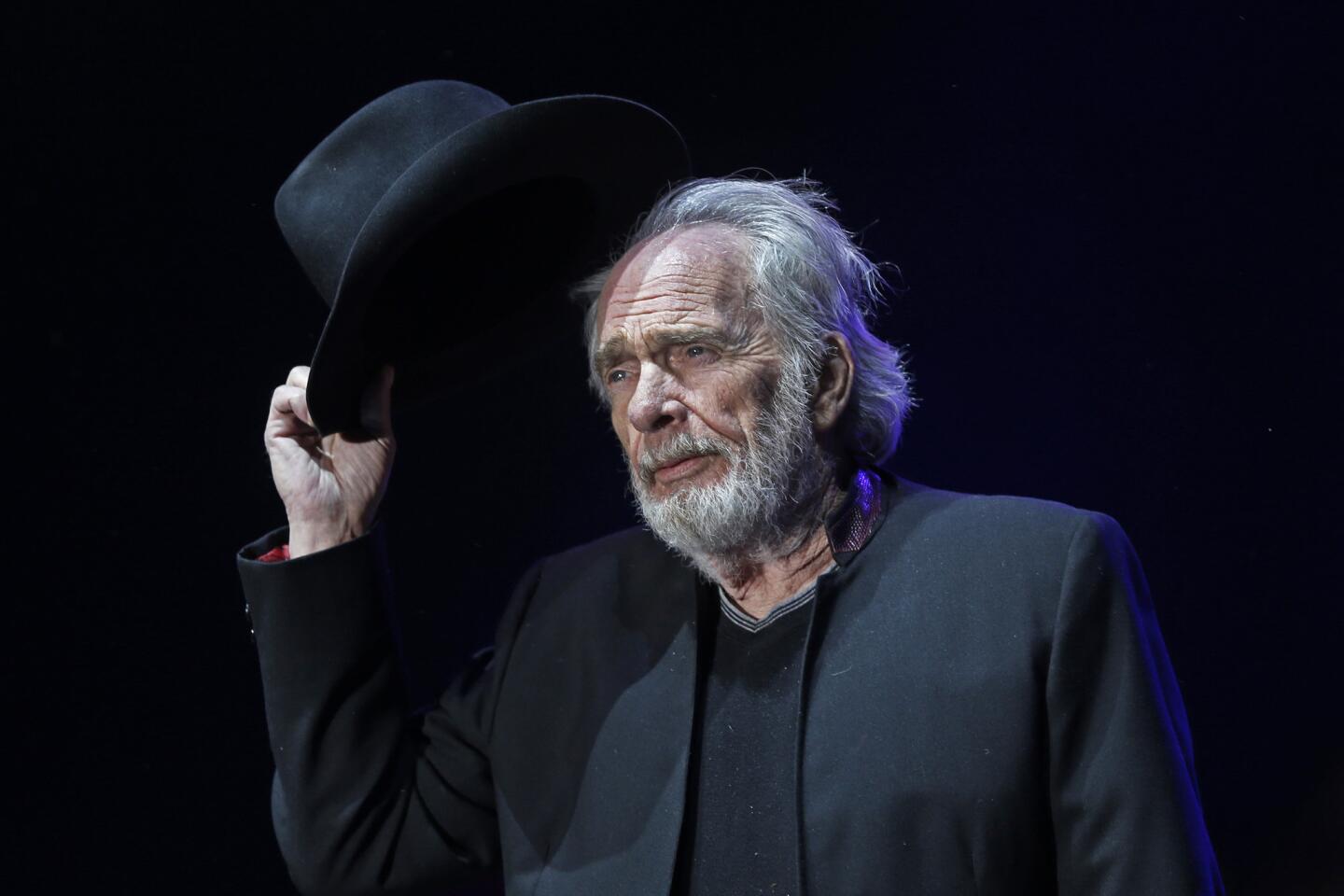

Merle Haggard: The authentic and gifted voice of the people

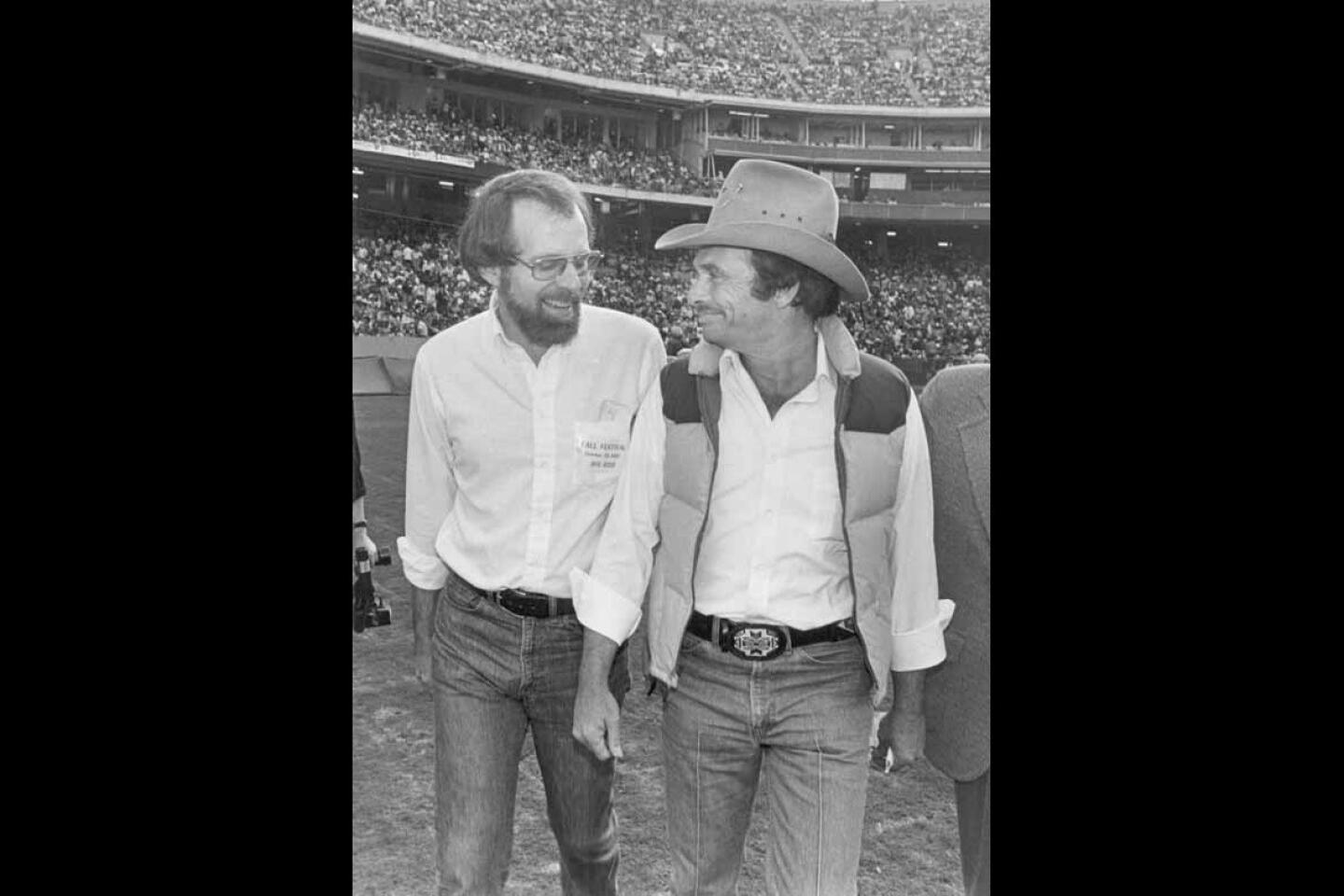

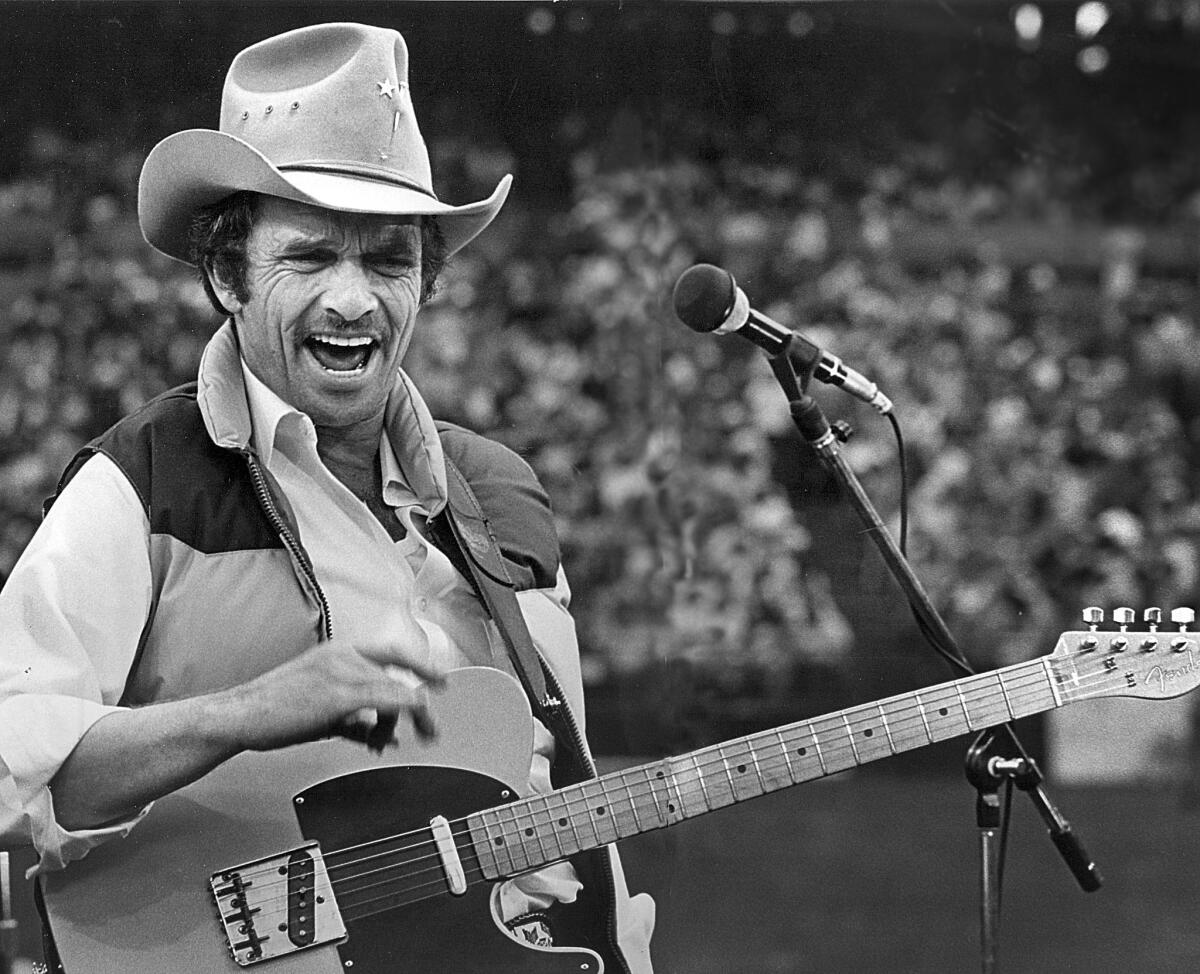

Merle Haggard in concert at Anaheim Stadiium in 1980.

- Share via

Merle Haggard’s songs always seemed to channel the people he sang for through his 79 years: blue-collar workers, prison inmates, forlorn lovers and everyday Americans looking for signs of reassurance or stability as their world changed around them.

He didn’t invent the so-called “Bakersfield sound” in country music, a punchier, twangier, edgier counterpoint to what was coming out of Nashville’s recording studios in the 1950s and ‘60s. That credit belongs to some of Haggard’s predecessors in the oil- and agricultural-rooted community: Tommy Collins, Bill Woods, Wynn Stewart and, the first bona fide country star out of Bakersfield, Buck Owens.

But Haggard, born in nearby Oildale, quickly became the most erudite and insightful voice of the Bakersfield sound. In song after song, he articulated with utter authenticity the dreams, the fears, the hurts, the hopes of not just his fellow Americans, but his fellow human beings.

In his first Top 5 country hit, “Swinging Doors” from 1966, he freshened up the even-then clichéd subject of the hapless guy booted out of his home, forced to take up residence at the local honky tonk:

I’ve got everything I need to drive me crazy

I’ve got everything it takes to lose my mind

And in here the atmosphere’s just right for heartaches

And thanks to you I’m always here till closing time

Honky tonk laments were just the tip of the iceberg. If folk-protest hero Woody Guthrie had a lifelong country music ally and disciple in his unflagging empathy for the plight of working people, it was Haggard. Time and again he returned to the subject of those who have to scratch out a living any way they could in the land of plenty.

In “I Take A Lot of Pride in What I Am” from 1969, he sang of one who owned his place on society’s fringes, and keeping his head unbowed:

Home is anywhere I’m livin’

If it’s sleepin’ on some vacant bench in City Square

Or if I’m workin’ on some road gang

Or just livin’ off the fat of our great land

I never been nobody’s idol, but at least I got a title

And I take a lot of pride in what I am

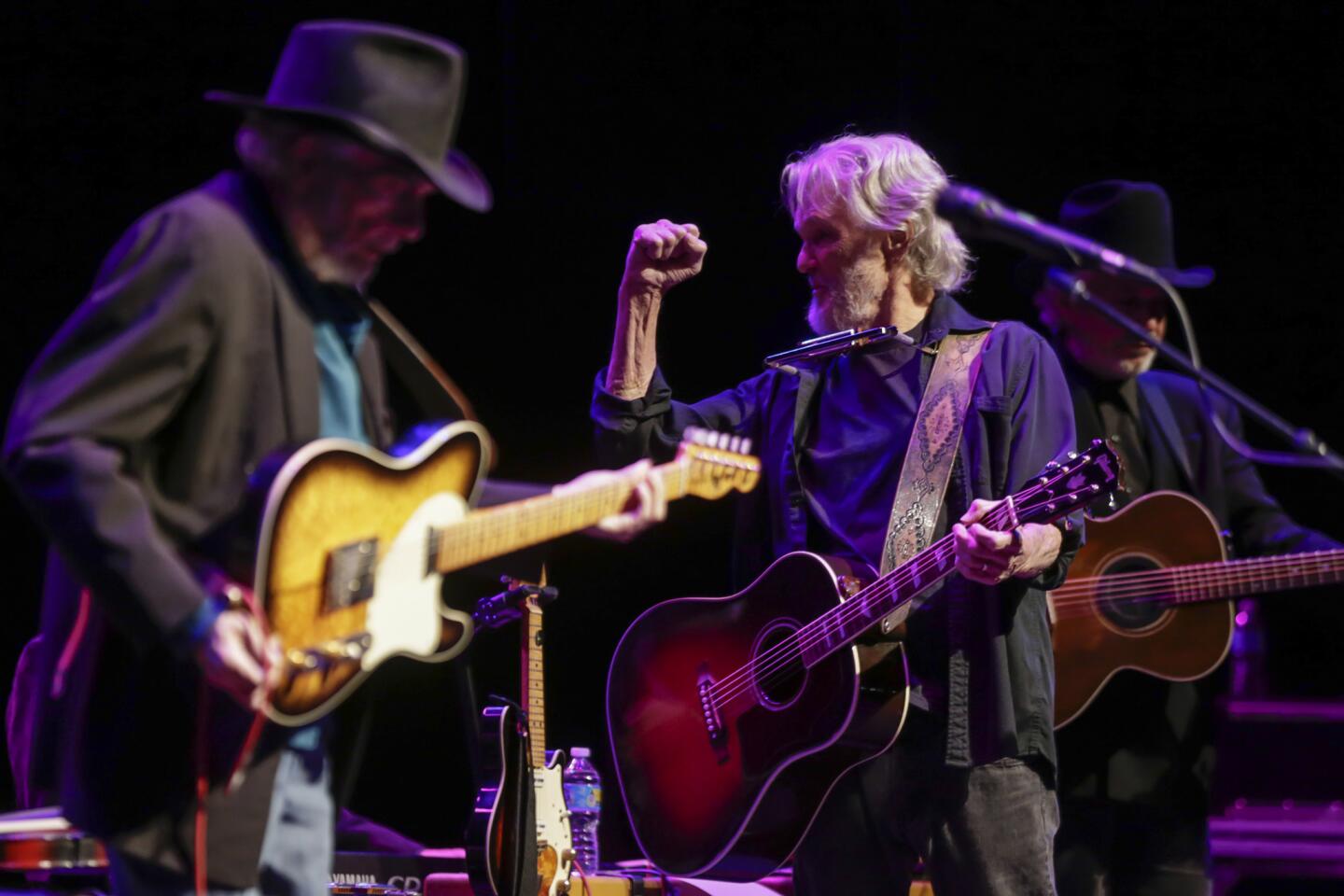

Merle Haggard performances

His love songs are among the best ever written, which is why they’ve been recorded and performed by others extensively over time. “I Started Loving You Again,” from 1968, has a lyrical nod to Owens’ earlier hit “Crying Time,” yet still became a country classic on its own:

What a fool I was to think I could get by

With only these few million tears I’ve cried

I should have known the worst was yet to come

And that crying time for me had just begun

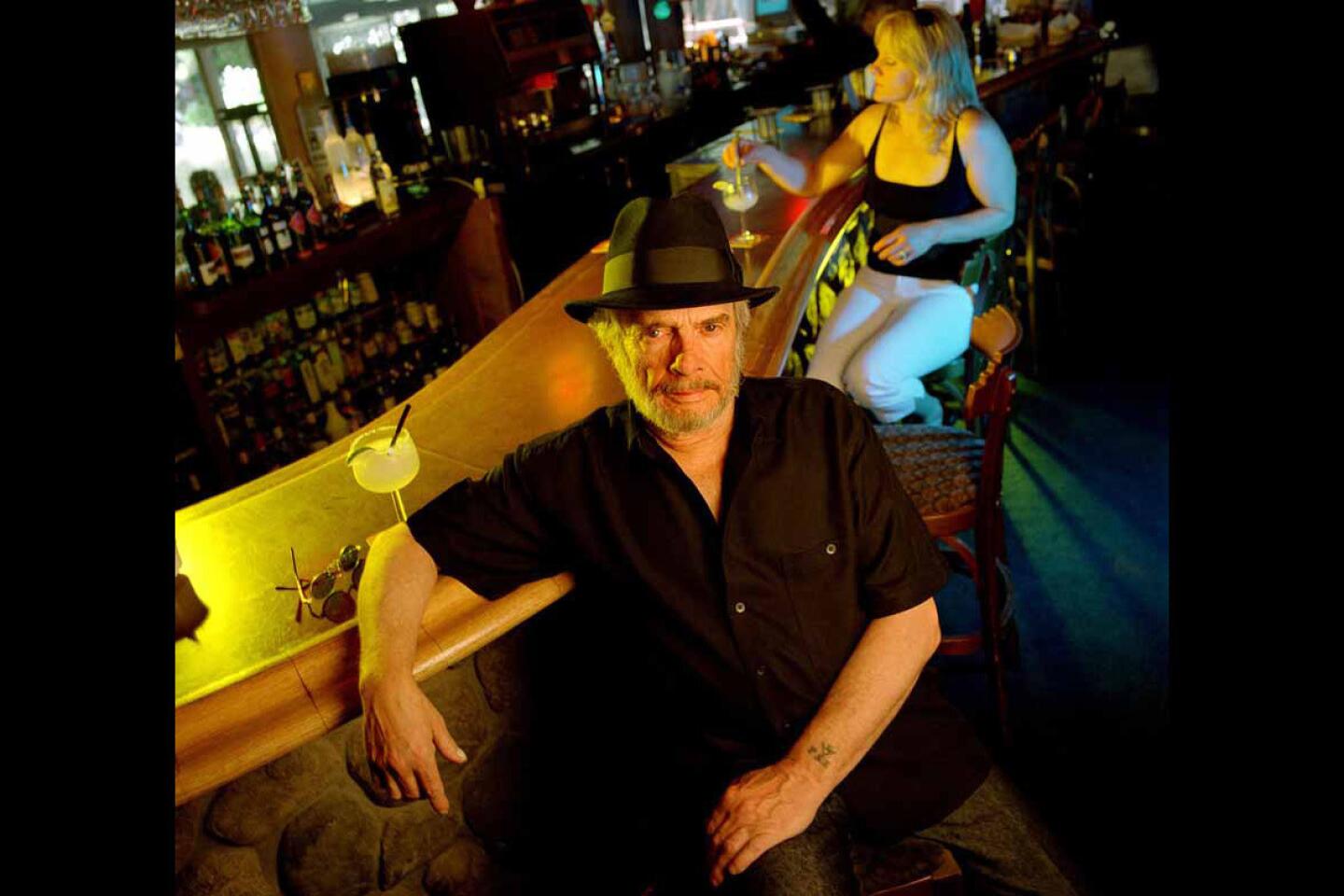

As a music fan who has loved country music since I can remember — part of my DNA thanks to my mother’s roots growing up during the Depression in the coal-mining country of eastern Kentucky — I’ve taken every opportunity that cropped up to connect with Haggard during my years covering popular music for The Times.

I always came away from conversations with him impressed at the unhurried, absolutely attentive way he formed and expressed thoughts. There was a palpable sense of him weighing perspectives and consequences of any remark he might care to share.

And when you sat with him, you had his full, undivided attention — unlike many of the celebrity interviews conducted assembly-line fashion in hotel suites these days.

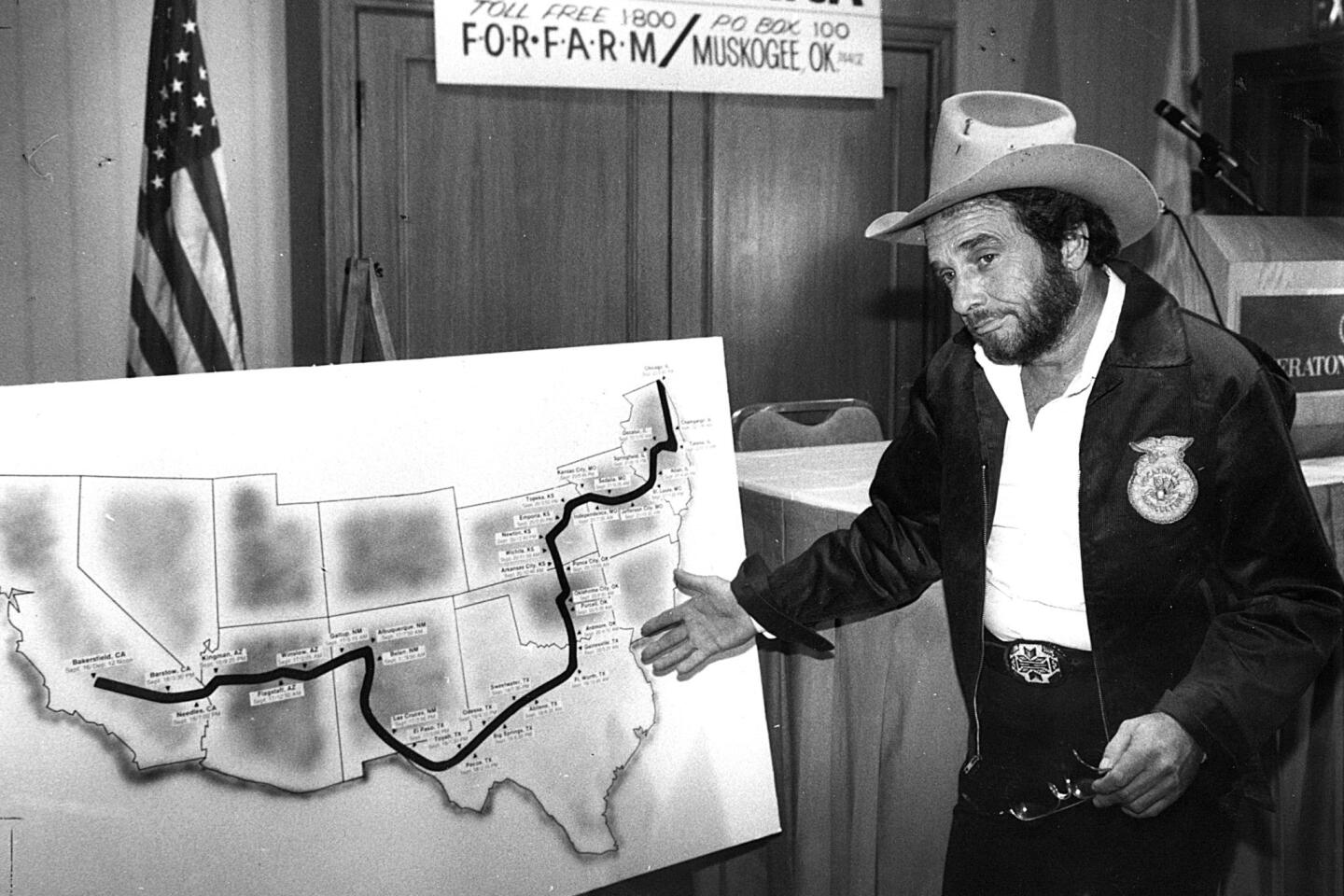

Haggard was long a favorite of political conservatives, in no small part because his early anthems seeming to espouse traditional values such as “Okie From Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me.” Yet when Democrat Barack Obama was elected president, Haggard was filled with patriotic pride.

“I think we’re probably guilty of living up to the Constitution for the first time in the history of America — which is really something to say,” Haggard told me in 2009. “In my lifetime, they were still lynching blacks without a court, without a trial. To see it come all the way to [an African American] being elected president is really something.”

Every time I watched him sing “Okie From Muskogee” — outwardly poking fun at the hippie peace-and-love generation that was in full flower when he wrote it in 1969 — I tried to discern whether he was being sincere, or being slyly ironic. I finally concluded it was a little of both, which also was part of his great gift as a writer.

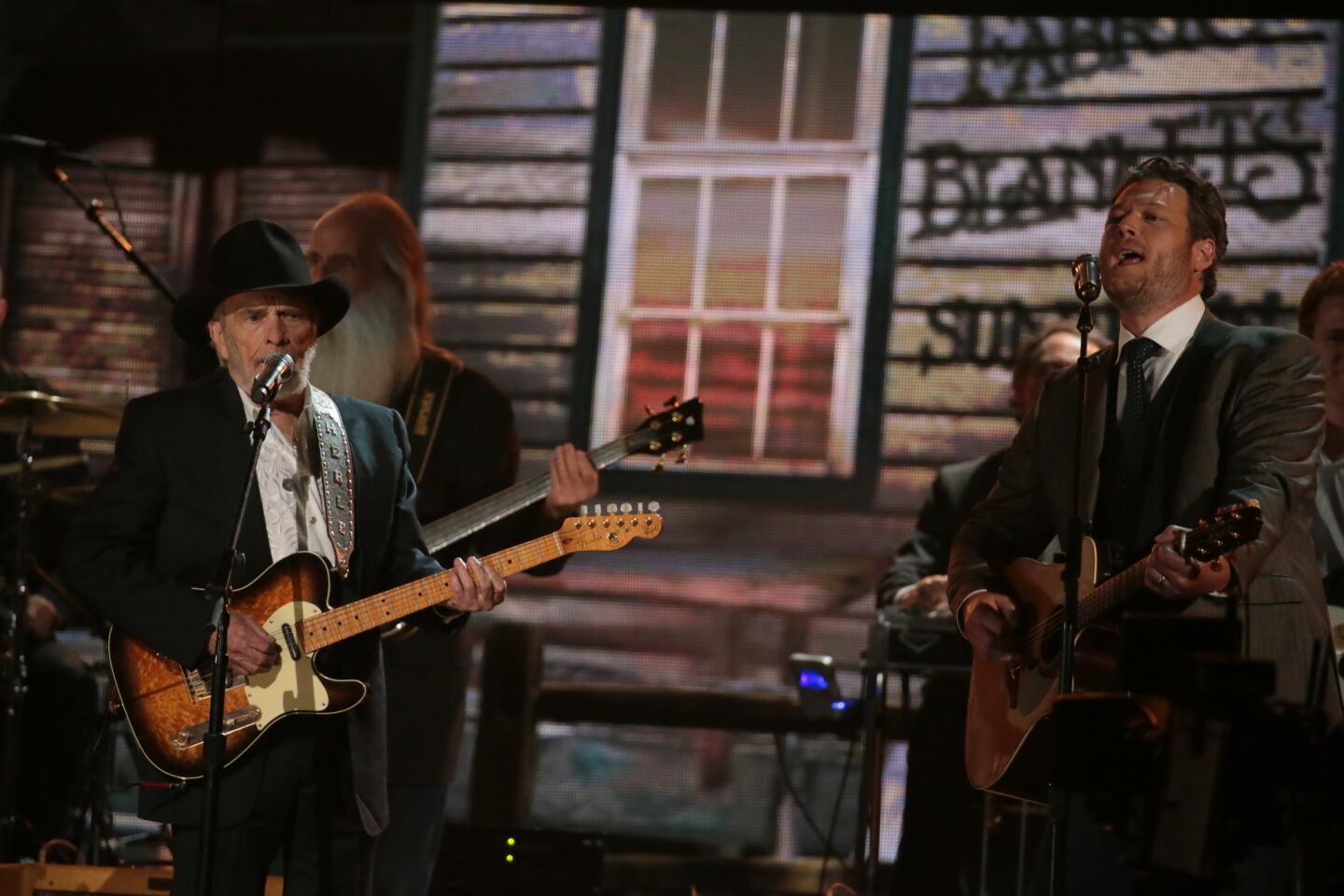

Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens and Glen Campbell perform on a TV show in the mid-1970s.

As much as anyone, he recognized that life wasn’t etched in black and white but in a full complement of colors. And like Mark Twain, Haggard could convincingly capture the attitude of any number of characters in his songs, without necessarily internalizing the views he helped them express.

For himself, Haggard fully embraced rather than trying to hide or sugarcoat his own past as a petty criminal, a delinquent whose escapades landed him in state prison in San Quentin as a teenager. Even after devoting himself to a life in music rather than crime, he struggled — with divorce, with finances, with the bottle.

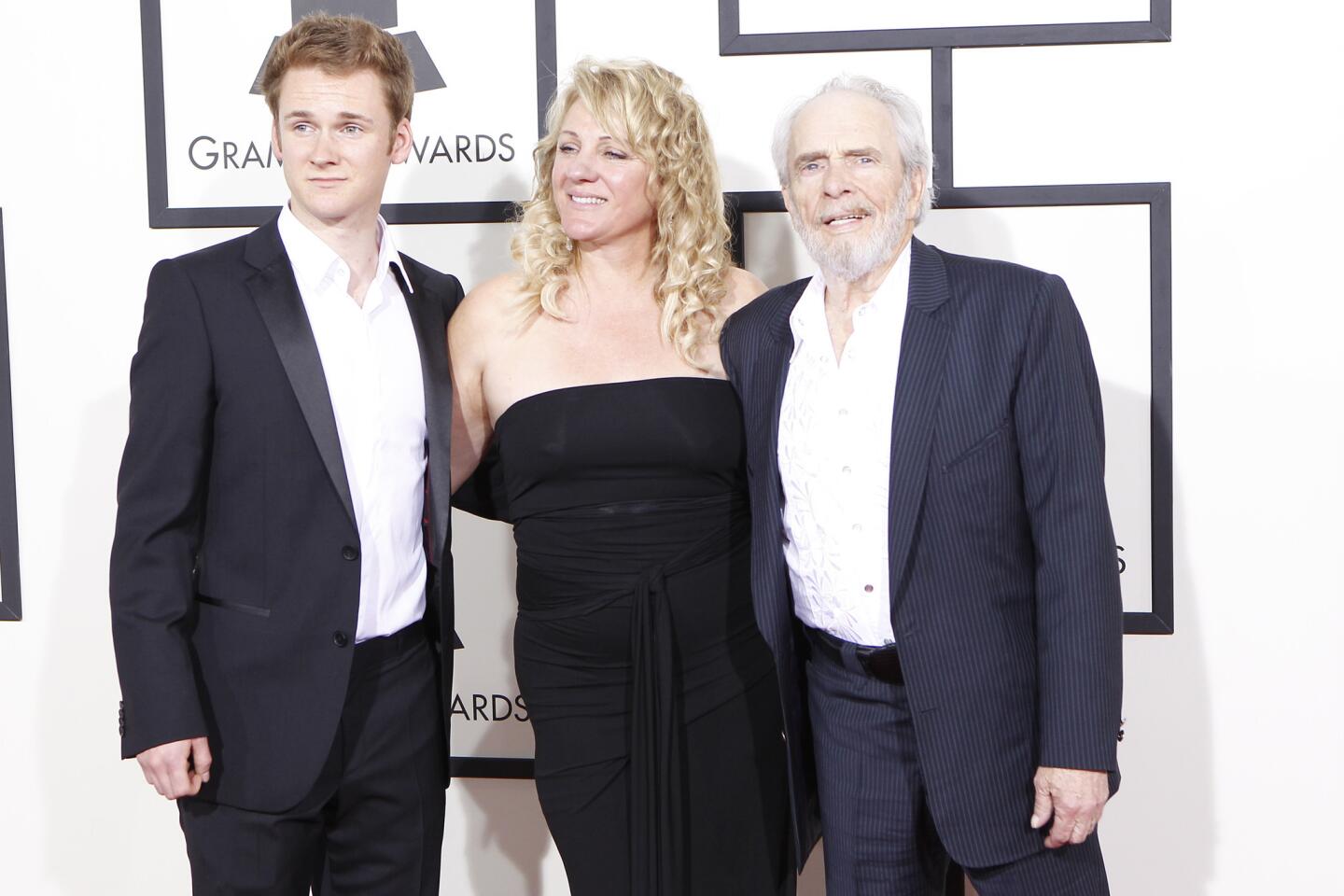

Some of his most heartfelt songs came out of his desire to be forthright with his children about his past. In 2000, he recorded “I’m Still Your Daddy,” aimed at the young children of his 1993 marriage to Theresa Lane.

It’s true I’ve done some time in prison

Let me be the first to tell you I was wrong

That was back when I was wild

Back when I was just a child

Back before your mama came along…

Don’t put me down

Don’t push me away

Daddy needs some family love today

He had intense pride in, and love for, his family — no doubt in part because his own father died when Merle was just 9, a fundamental void that more than likely contributed to his youthful rebellion.

He once told me about his then-teenage son, Ben, and how much more accomplished a guitar player he had become than Haggard felt he’d ever been, even though Haggard was widely respected as an instrumentalist almost as much as he was as a singer and a songwriter.

He backed up the assertion by welcoming Ben into his lauded band, the Strangers, always one of the most versatile and accomplished ensembles in country music — a unit that wouldn’t tolerate any second-rate players, family or no.

Ultimately, however, it’s Haggard’s songs — more than his influential vocal style or his skill as a bandleader — that will be his greatest legacy.

“He was probably the best combination of country singer and songwriter of his generation,” former Times pop music critic Robert Hilburn said by email Wednesday morning.

“When he started out, he said he wanted to sing as good as Lefty Frizzell and write as good as Hank Williams,” recalled Hilburn, who also spent numerous hours interviewing Haggard on many occasions over several decades. “That dream pretty much came true.”

Twitter: @RandyLewis2

MORE:

Video playlist: Merle Haggard performances

Merle Haggard by the numbers: his gold and platinum albums

From the archives: Merle Haggard, Kris Kristofferson show songwriting at its best

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.