Pete Seeger wielded his ‘Hammer’ with melodic clarity and civic grace

- Share via

Pete Seeger was best known as a folk singer, an archivist and writer, and the purveyor of such beamed-from-the-heavens standards as “We Shall Overcome,” “If I Had a Hammer” and “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

But among the musician’s most important roles was one that’s often overlooked: that of an American citizen who understood the power of song to serve as messenger, as Trojan horse, as lightning rod.

It’s hard to imagine a song steering and stirring more than “We Shall Overcome.” The work long ago became less the domain of Seeger, who helped popularize it when he published it in “People’s Songs,” than a sacred text owned by anyone longing for justice. Its lines have been aimed against countless seemingly immovable institutions of oppression. Adapted from the tune of an old spiritual, the message of the opening verse is as profound yet simple as a Zen koan. “We shall overcome. Deep in my heart I believe we shall overcome someday.”

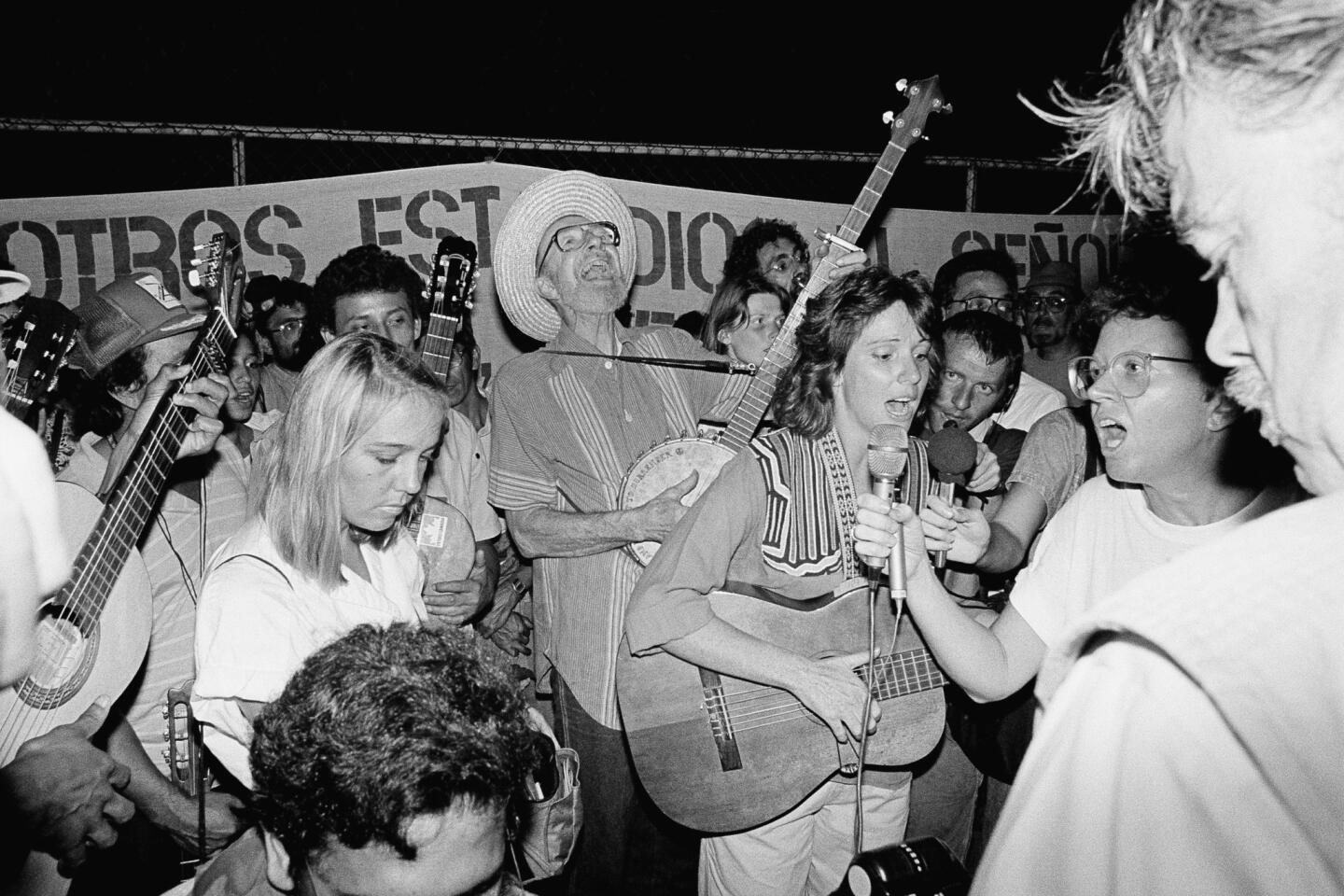

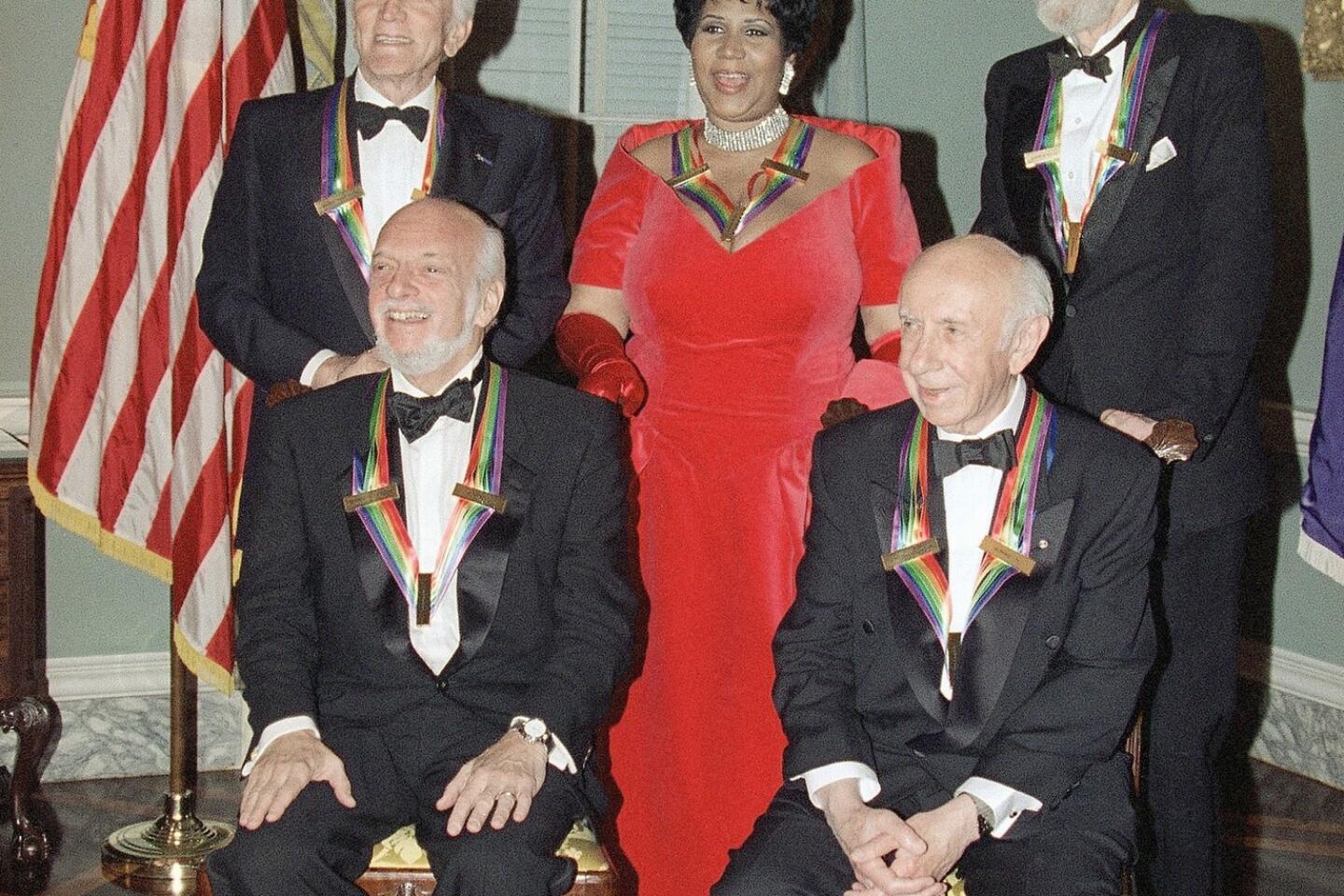

PHOTOS: Pete Seeger, activist and humanitarian

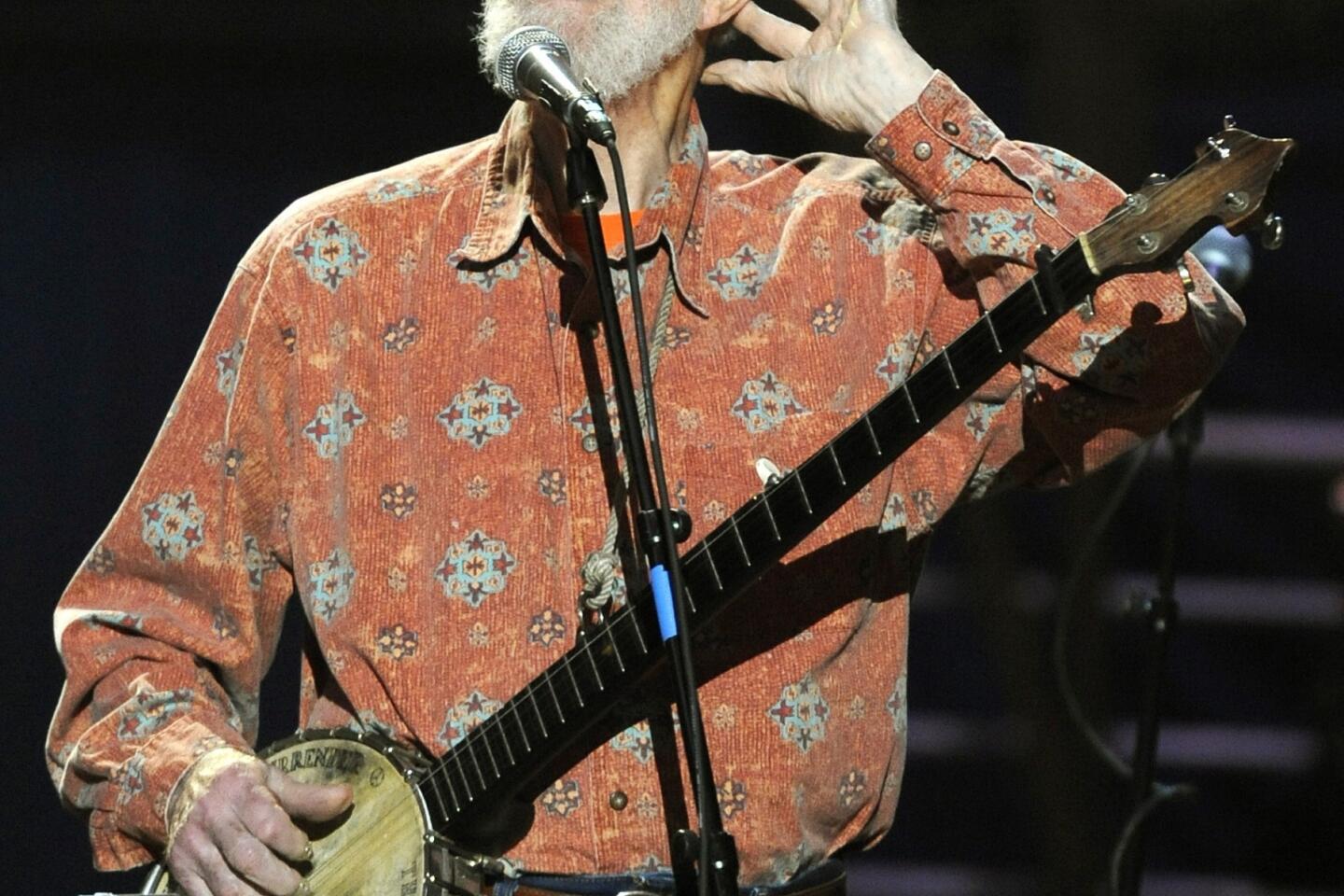

Folk music’s most consistent advocate and a tireless worker for justice, Seeger, who died Monday at age 94, was accurately described by poet Carl Sandburg as “America’s tuning fork.” He released his first solo album for the fledgling folk label Folkways in 1953 after years spent with the group the Weavers, and over the next six decades compiled a body of 52 studio albums.

As a self-described “student of American folklore,” he sang for millionaires and for union gatherings, was criticized as a mouthpiece for Joseph Stalin’s Russia while inculcating a generation of soon-to-be troubadours through children’s folk tunes albums. He traveled the South during the civil rights movement to fire up activists. During the Vietnam War he was censored by CBS after taping a version of “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” a parable about a clueless leader guiding his troops toward certain demise.

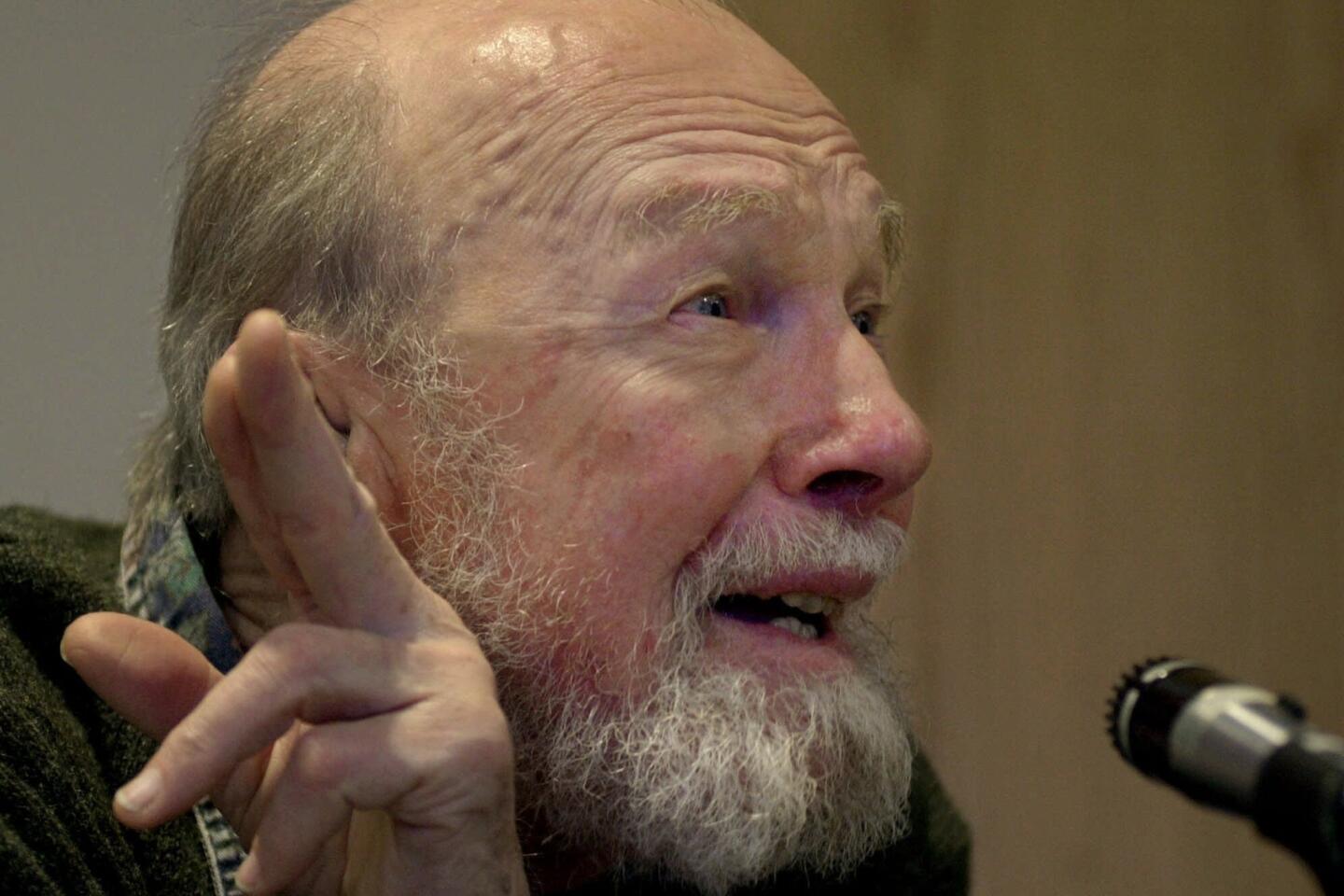

No event, though, presents a more vivid picture of Seeger than his clear, stubborn responses to questioning after being called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955.

PHOTOS: Celebrities react to Pete Seeger’s death on Twitter

Facing congressmen probing the so-called Communist infiltration of America, Seeger, a longtime union activist and World War II veteran, responded with measured outrage. The Harvard-educated artist had already become famous with the Weavers, who’d landed on the top of the Hit Parade with their version of Lead Belly’s “Goodnight, Irene.”

He was asked by a member of the committee whether he’d performed his song about the utility of hard work and community, “If I Had a Hammer,” at a Communist meeting. Seeger declined to answer that or any such questions “as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs.

“I love my country very dearly,” he said, adding that he resented the implication that it mattered where and to whom he had sung his songs, or that “some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, or I might be a vegetarian, make me any less of an American.

“I will tell you about my songs, but I am not interested in telling you who wrote them, and I will tell you about my songs, and I am not interested in who listened to them.” The committee pressed further, asking about the locations of other performances. He steered his response toward the meaning of his lyrics, but the congressmen ignored him.

PHOTOS: Pete Seeger | 1919 - 2014

To that, Seeger replied wryly: “I am sorry you are not interested in the song. It is a good song.”

That’s an understatement. One of the most enduring affirmations of the 20th century, “If I Had a Hammer” and his other work will be the musician’s artistic legacy, where it will take its place beside texts of Walt Whitman and Mark Twain as archetypally American chronicles.

Seeger’s refusal before the subcommittee, though, serves as a reminder of the power and importance of his great big No as a citizen, as well as to the way in which art can steer and stir conversations on a grand scale.

Those in power had reason to fear Seeger, a one-man conspiracy who went on to infiltrate American culture one child, church and community center at a time. As a young man he worked archiving old songs for folk music documentarian Alan Lomax. He hit the road with Woody Guthrie, bringing to life classic American work songs.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

After facing scrutiny by McCarthyites, a less convicted man would have checked himself, perhaps retreated to a day job as an archivist at the Library of Congress. Instead, he continued recording work songs, and issued more volumes in his series of influential children’s folk albums, which became generational touchstones. With his late wife of more than 70 years, Toshi, guiding their finances, the pair became a force.

Fans of the grittier, less practiced “real folk blues” as presented by Dock Boggs and Woody Guthrie were less impressed with Seeger’s earnest style. An Ivy League man with a mellifluous voice, Seeger was the acceptable face of a music that previously seemed alien to an America smitten with Perry Como and Patti Page.

He filtered the spirit of hand-me-down American music through the voice of an enthusiastic, well-intentioned outsider wholly devoted to equality, even if in the process he blunted some of the discordant edges that gave the music its raw power.

In exchange, though, Seeger offered a truth that was as undeniable as his steady tone and assured picking on the banjo. “I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion, and I am proud that I never refuse to sing to an audience, no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation in life,” he defiantly told the subcommittee in 1955.

“I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody,” he said. “That is the only answer I can give along that line.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.