Julie Chen and other spouses caught up in the #MeToo era face a difficult decision

“The Chenbot.”

That’s the affectionate nickname devoted fans of the CBS reality show “Big Brother” gave host Julie Chen, a tribute to her mechanical precision and cool detachment amid the often sordid and outrageous shenanigans of the “houseguests.”

But when Chen, who has hosted “Big Brother” since its premiere in 2000, signed off at the end of a live episode Sept. 13, she went off script in dramatically uncharacteristic fashion.

“I’m Julie Chen Moonves,” she said. “Goodnight.”

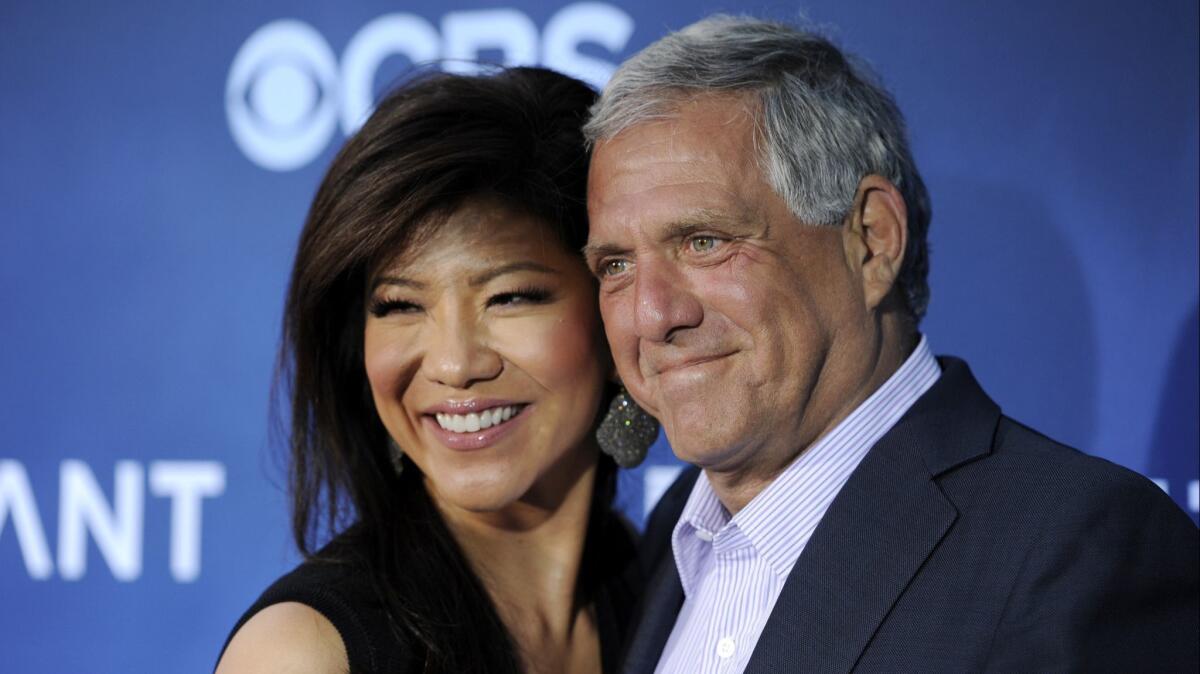

Under normal circumstances, Chen’s use of her married name might have been met with a shrug. But coming in her first on-air appearance since her husband, Les Moonves, resigned from CBS amid allegations of sexual harassment and assault days earlier, those two syllables sent a jolt across the Twitterverse.

It was hard to interpret the signoff as anything other than a show of support for her embattled spouse, who for 15 years had reigned as chief executive of CBS, and a rebuke of his corporate rivals. Some even saw it as a swipe at the dozen women who’ve gone on the record with allegations against Moonves dating to the 1980s.

“Tonight, Julie Chen signed off Big Brother as Julie Chen Moonves, firmly standing w/her husband, a serial sexual assaulter who ruined careers,” tweeted Danny Deraney, a publicist whose clients include one of Moonves’ accusers, Illeana Douglas. “She is complicit.”

The outcry hasn’t deterred Chen, who has continued to use her married name on “Big Brother” and is slated to return next season as host of the long-running reality show. But her husband’s alleged improprieties have already taken a professional toll. In a videotaped message Sept. 18, she tearfully announced she’d be leaving “The Talk,” the CBS daytime show she’s moderated since its debut in 2010, to spend time with her family.

The controversy surrounding her husband has thrust Chen — and her high-profile marriage — into the spotlight, a rarity for a woman who’s made a career out of calmly observing the drama rather than being a part of it, of being an accessory to voyeurism rather than the object of it.

It also illustrates the difficult predicament faced by the partners of men disgraced by allegations of misconduct who, fairly or not, are often accused of complicity or willful blindness.

A year after devastating reports about Harvey Weinstein were published in the New York Times and the New Yorker, the #MeToo movement continues to rage. Thanks to Louis C.K. and others who’ve tested the comeback waters, there’s already been much fitful discussion of how, when and whether men might redeem themselves after allegations of sexual misconduct. But for loved ones caught up the wake, navigating is even sketchier.

Chen declined to comment for this piece, but a source close to her told the Times that the use of her legal married name was meant “to simply express love and support for her husband, and to stop further speculation and inquiries into the status of their marriage.”

“She is between a rock and a hard place,” said Aisha Tyler, who co-hosted “The Talk” with Chen from 2011 until last year and believes her friend’s decision to leave the Emmy-winning show was “a really deep personal sacrifice: I know how hard she worked to make it great.”

Last fall, Georgina Chapman faced a similar dilemma as Weinstein’s wife. Like Chen, she was professionally linked to, if not dependent on, her husband: Her fashion line, Marchesa, was a favorite on the red carpet and was often worn by the stars of Weinstein’s films. But days after numerous women went on the record to accuse the once-untouchable producer of sexual assault, harassment and rape, she announced their marriage was over and said her “heart breaks for all the women who have suffered tremendous pain because of these unforgivable actions.”

She lay low for seven months — a time when no high-profile star wore Marchesa on awards show red carpets — before launching what appeared to be a carefully synchronized comeback attempt in May that included a sympathetic profile in Vogue, complete with a portrait by Annie Leibovitz and an editor’s letter from Anna Wintour, plus an appearance by actress Scarlett Johansson in Marchesa on the red carpet of this year’s Met Gala, chaired by Wintour. The effort met with a mixed reaction, with some questioning whether Chapman’s story needed telling quite so soon.

Unlike Chapman, Chen has not publicly renounced her husband. Instead, she’s repeatedly expressed support for him. After Ronan Farrow published his first expose on Moonves in the New Yorker in July, she issued a statement on Twitter.

“Leslie is a good man and a loving father, devoted husband and inspiring corporate leader,” she said. “He has always been a kind, decent and moral human being. I fully support my husband and stand behind him.” Later on “The Talk,” Chen reiterated that she would stand by her statement — and, presumably, her husband — “today, tomorrow, forever.”

Her public devotion to Moonves is “a huge slap in the face to the entire movement and to women everywhere, to survivors,” said Deraney, who also represents Weinstein accuser Rosanna Arquette, in an interview. “All you’re doing is lighting a fire that’s most likely going to end up burning you.”

Chen’s decision to stick it out with Moonves is perhaps less unusual than one might think. In the final weeks of the 2016 campaign, Melania Trump dismissed the numerous women who’d accused her husband of sexual assault as liars. She also brushed off the “Access Hollywood” tape in which Trump is heard bragging about being able to grab women inappropriately because he was a celebrity, as “boy talk.”

Camille Cosby, the wife of disgraced comedian Bill Cosby, has repeatedly defended her husband in dramatic fashion, calling his conviction on charges of sexual assault in May “mob justice” and likening his predicament to that of lynched teenager Emmett Till.

The tableau of the downcast wife standing (or sitting) beside her partner in a moment of crisis is so pervasive, it inspired “The Good Wife,” the acclaimed legal drama that aired on Moonves’ network, CBS, for seven seasons. It made “Weiner,” about the doomed mayoral campaign of disgraced congressman Anthony Weiner and his now-estranged wife, Huma Abedin, a must-see documentary, and it gripped the nation once again last week as a stricken-looking Ashley Kavanaugh watched silently as her husband, Brett, angrily defended himself before the Senate Judiciary Committee against allegations of attempted rape.

Then there’s Hillary Clinton, who first entered the national conversation thanks to an infamous “60 Minutes” interview in which she and her husband, then a contender in the Democratic presidential primary, addressed a reported affair with Gennifer Flowers.

“You know, I’m not sitting here, some little woman standing by my man like Tammy Wynette,” she said defiantly, an Arkansas twang in her voice. “I’m sitting here because I love him, and I respect him, and I honor what he’s been through and what we’ve been through together.

Of course, Clinton did just that — standing by her husband through infidelity and much more serious charges of rape and sexual harassment. What some see as loyalty, others have interpreted as political calculation. But in either case, Clinton has been haunted by her decision for decades, perhaps most vividly at the final debate of the 2016 presidential campaign, where several of her husband’s accusers were invited to sit in the audience by the Trump campaign.

Like most of these women, Chen is accomplished in her own right. Raised in Queens by parents who immigrated to the U.S. — her father from China, her mother from Myanmar— the 48-year-old USC graduate started her on-camera career as a reporter at a local station in Dayton. After two years, she returned to her hometown to work for WCBS and rose quickly to become news anchor of “The Early Show,” the network’s national morning program, in 1999.

She began hosting “Big Brother” in 2000 while continuing at “The Early Show,” and married Moonves in 2004. Co-workers who spoke with the Times praised her work ethic and rejected the notion that she used her relationship with the network’s chief — their boss — to get ahead.

“Big Brother” has been a steady ratings performer during the doldrums of broadcast summer and inspired an unusually fanatical audience. It’s also become a subject of perennial controversy, thanks to housemates who toss around racial epithets and homophobic slurs with alarming regularity. This season, a contestant named J.C. Mounduix was accused of sexual misconduct multiple times.

Chen’s reserve has always stood in contrast to the craziness. In early seasons, she came off to many as stilted — an impression captured in a montage of her repeating the catchphrase “but first” dozens of times. She’s since loosened up but is less essential to the show than the hosts of comparable reality shows, like Jeff Probst of “Survivor.”

“Her role on ‘Big Brother’ only involves one hour a week in a show that broadcasts three episodes and live feeds,” said TV critic Andy Dehnart of the website Reality Blurred. “She has very little opportunity for improvisation and reaction, and she’s also physically removed from the contestants and only interacts with them as they’re leaving the game.”

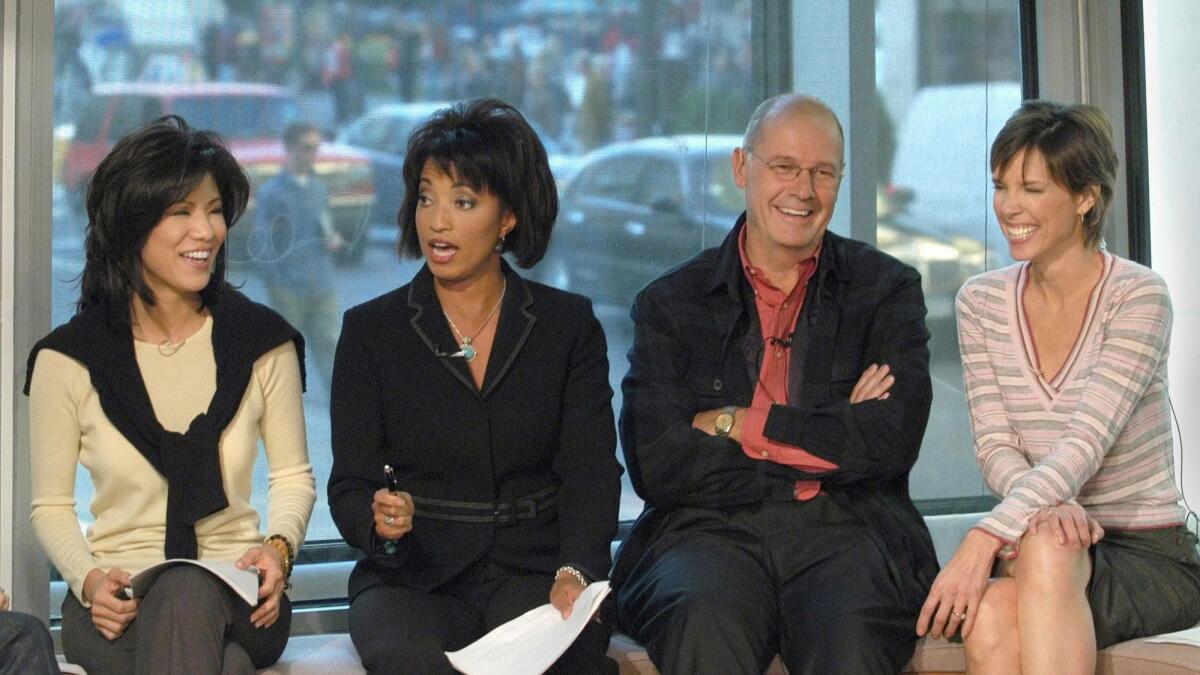

When she helped launch “The Talk” in 2010, she found that moving into the confessional space of daytime television was a challenge.

“I didn’t know how to talk about my feelings on television [because] my whole career was spent keeping my mouth shut about what I think of topics,” Chen told Buzzfeed in 2015. After a rocky first season, the show stabilized and has twice won the Daytime Emmy for entertainment talk show.

While “Big Brother” cuts off the outside world, sequestering contestants in a house without access to phones, radio or the internet, “The Talk” thrives on the news of the day, making it all but impossible for Chen to stay (particularly after her co-hosts expressed their support for Moonves’ accusers after a second report was published in the New Yorker). Even before the Weinstein allegations broke, abuse by powerful men had been a fixture of conversation on the show. In a clip from 2015 that now seems prescient, the co-hosts discussed Camille Cosby’s loyalty to her husband in the face of mounting allegations.

“A lot of times, when you’ve believed something about somebody for such a long time and you realize it’s not true,” said Aisha Tyler, as Chen looked on impassively, “it’s not just that you’re disappointed in the other person; you’re disappointed in yourself for believing a lie for so long. It’s easier to deny the truth and protect your own sense of self.”

ALSO

Hollywood and Wall Street wonder how the show will go on at CBS without Leslie Moonves

The two lessons from Les Moonves’ ouster

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Follow me @MeredithBlake

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.