Heat waves are deadlier than hurricanes and fires. Maybe they should get names, too

Hurricane Katrina. Superstorm Sandy. The Camp fire.

These names evoke powerful images and memories of lives lost and communities torn apart. They also remind us that extreme weather is becoming more dangerous as the planet heats up, serving as a potent call to action.

But what about the heat wave that struck much of the eastern half of the United States in 1980? Nobody ever gave it a name. Until this week, I’d never heard of it. But the direct death toll was 1,260, and heat stress contributed to an estimated 10,000 deaths, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

That’s almost twice as many people as were killed directly by Katrina, Sandy, the Camp fire and also the 9/11 terrorist attacks — combined.

If the 1980 event had been assigned a name, would more people remember it today? If it had been announced as a Category 5 heat storm — with meteorologists, journalists and elected officials sounding the alarm — would more people have stayed home, or decamped for cooling centers, or done a better job staying hydrated?

How many fewer people would have died?

Giving heat waves the same treatment as hurricanes isn’t a new idea. But it got a boost this week when the Atlantic Council launched the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance, a global coalition of cities, nonprofits, scientists, companies and government agencies whose first major initiative is developing a worldwide standard for naming and ranking heat waves.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Heat waves pose a serious threat, which is why I’ve written about them before. Especially vulnerable are groups such as the elderly, outdoor workers, people without homes, low-income families who can’t afford air conditioning, and individuals with medical conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. A recent study led by Duke University researchers estimated that during the last decade, the Lower 48 states averaged 12,000 heat-related premature deaths each year.

There’s no question climate change is making extreme heat worse, and will continue to do so as long as we keep burning fossil fuels and cutting down forests. Already, major U.S. cities are experiencing three times as many heat waves as they did in the 1960s, with a heat wave season that is 47 days longer now than it was then, according to federal government scientists.

Despite those realities, most people aren’t especially worried about extreme heat.

“Heat waves are different than floods and hurricanes, because floods and hurricanes affect physical infrastructure. And so they’re visible. You can see the impacts,” said Jennifer Marlon, a research scientist at Yale University’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. “Heat waves primarily affect human health, much more than infrastructure.”

Marlon coauthored a study last year that examined how Americans perceive the health risks of extreme heat. The results — based on a national survey conducted by the researchers, coupled with some fancy modeling — are fascinating.

The researchers found that while Americans aren’t super worried about extreme heat overall, risk perceptions vary by geography and demographics. Areas with more residents over age 65 express relatively less worry about extreme heat, even though elderly people are among the most vulnerable. And areas with more Latino, low-income and female residents tend to be more concerned than whiter, wealthier and more male communities.

Marlon said those latter findings track with other research showing that men — white conservative men, in particular — tend to have lower risk perception in general. They also track with surveys showing that Latinos are more concerned about climate change than other racial or ethnic groups.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Marlon and her colleagues found that people living in the warmer southern half of the U.S. see extreme heat as a greater risk than their counterparts to the north. Here are two maps from the study, the first showing risk perception at the state level and the second narrowing in on individual counties:

You might think it’s good that people in hotter places are more concerned. But residents of cooler areas are still vulnerable, especially as the planet warms. Their bodies are less acclimated to extreme heat, and they may not have air conditioning.

Why does this stuff matter? Because if we were all sufficiently worried about heat waves, we might be more likely to take precautions, like drinking enough water or avoiding strenuous activity. And governments might be more likely to take on systemic interventions, such as planting trees to create shade, replacing heat-absorbing pavement with green spaces and reflective surfaces, or reconfiguring energy efficiency incentives to favor the poor rather than the rich.

That’s where the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance’s work might help.

Kathy Baughman McLeod, a senior vice president at the Atlantic Council, said during a launch event Tuesday that the alliance is engaged in “productive and active talks” with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the World Meteorological Organization and the World Health Organization about developing a standard to name and rank heat waves.

The group’s 30 founding members include California’s elected insurance commissioner, Ricardo Lara. I was curious about his role, so I gave him a call.

Lara told me he grew up in East Los Angeles in a home with no air conditioning, and sometimes slept on the porch when the weather was hot. He said he’s especially concerned about California’s legions of agricultural workers.

“For people in the Central Valley, in Coachella, in the Imperial Valley, there’s no relief,” he said. “This is a risk that has never really fully been recognized.”

Lara is hopeful that naming and ranking heat waves can be a first step toward recognizing and confronting the true risks. In the long run, he’d like to develop “innovative insurance products” to help governments protect people from extreme heat, in line with the goals of his climate insurance working group.

“In policymaking, we have to grab people’s attention,” Lara told me. “We know that naming heat waves will provide clear levels of that risk, and more adequate warning to protect our most vulnerable Californians.”

Marlon, the Yale researcher, is similarly hopeful. She thinks naming and ranking heat waves would make it easier to talk about them, and would probably help the public and policymakers remember and learn from them.

“There’s real power in naming something and labeling it,” she said.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

America’s biggest gas utility is suing California over climate change policy. I continued my reporting on Southern California Gas Co. this week, writing about the company’s new lawsuit arguing that state officials have failed to promote natural gas as required by state law. Separately, a trade group of which SoCalGas is a leading member also sued state officials over the recently approved “advanced clean trucks” rule, which aims to put 300,000 zero-emission trucks on the road by 2035.

We’ve reached peak fire season, and California’s biggest conflagration right now is the Apple fire in Riverside County. My colleagues Louis Sahagun and Luke Money told the harrowing story of Jack Thompson, manager of the Whitewater Preserve near Palm Springs, who fled with his wife and was forced to speed through flames overtaking the narrow road out of the preserve. Louis and Joseph Serna also wrote about how COVID-19 is complicating evacuations and firefighting efforts.

It can be easy to forget that Los Angeles is named for a river, and that despite its concrete channel the L.A. River is still an important natural waterway. So I was heartened to see two stories about the river in The Times this week. First, Carolina Miranda wrote about a new augmented reality app that lets you explore the river’s history and complexity. And Lila Seidman talked with Angelenos who have taken up fishing in the L.A. River as a way to find peace during the pandemic.

ENVIRONMENTAL INJUSTICE

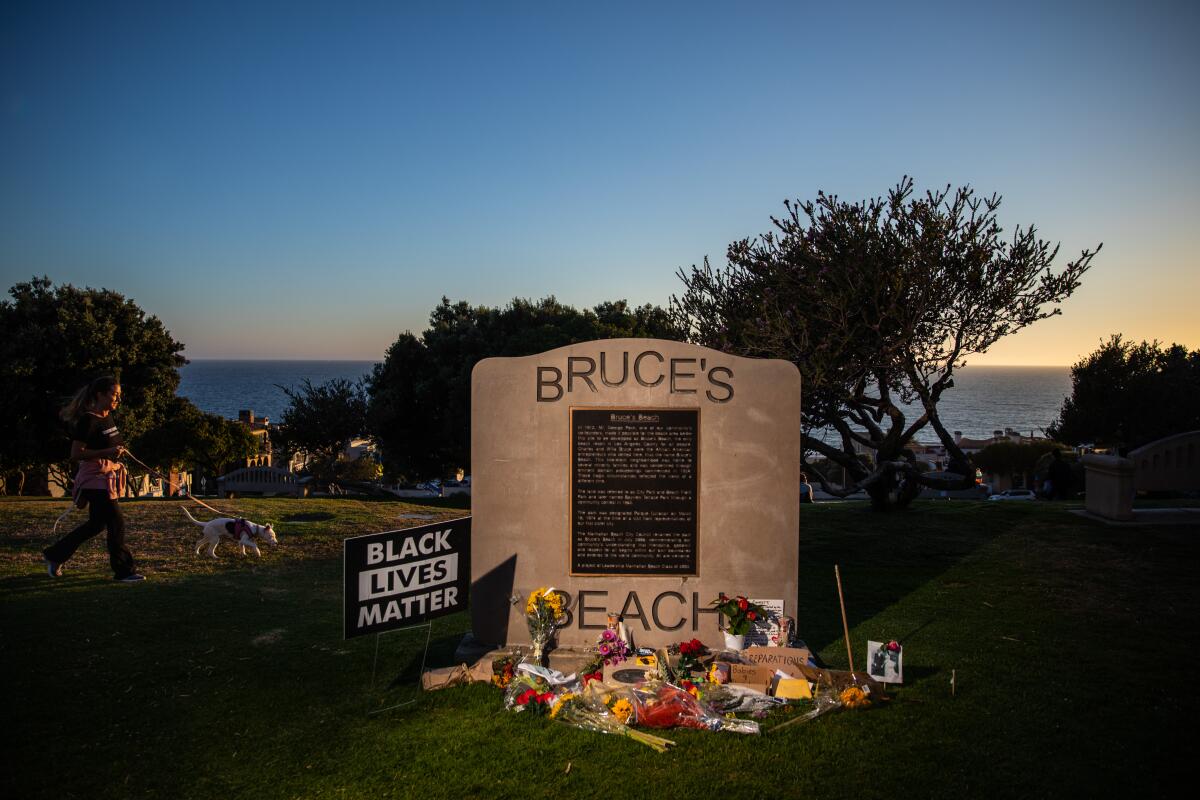

The California coastline is supposed to belong to everyone. But the reality is more complicated. Around a century ago, city officials in Manhattan Beach seized a slice of waterfront that was a haven for Black beachgoers and forced the Bruce family to sell its popular resort, as my colleague Rosanna Xia reports in an illuminating and infuriating story. Today, the city is facing a reckoning over its racist past as the real history of Bruce’s Beach comes to light.

Kern County is the oil industry’s political power center in California. But the city of Arvin, whose residents are mostly low-income and Latino, has become a leader in a statewide campaign to require buffer zones around oil wells, as Julia Kane reports for InsideClimate News. The campaign faced a setback this week when a state Senate committee rejected a bill to establish buffer zones. (On a related note, Arvin was also the only city I could find that voted down a request from SoCalGas to support “balanced energy solutions” that include natural gas.)

Extreme heat is projected to get much deadlier as temperatures rise. Building on this week’s discussion of heat waves, let me refer you to this story by the Arizona Republic’s Ian James, about a new study finding that heat could kill as many people globally as all infectious diseases combined if no action is taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And poorer countries would be hit hardest, because they’re less able to afford interventions such as air conditioning and better health care.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to The Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most, and makes newsletters like Boiling Point possible. Become a Los Angeles Times subscriber.

POWER STRUGGLES

Los Angeles has filed criminal charges against an oil company for allegedly failing to clean up abandoned wells. Officials say Allenco Energy has refused to comply with an order to properly plug wells at a South L.A. drill site to prevent leaking, as Emily Alpert Reyes reports for The Times. The oil wells are close to homes and schools — remember that story I shared earlier about the campaign for setbacks? — and have spurred complaints about nosebleeds and headaches.

Experts say forest thinning can help reduce wildfire severity by clearing out small trees and dead vegetation that provide fuel for fires. But these types of projects are rarely without controversy, and critics say they don’t always work as advertised. In California’s Los Padres National Forest, conservationists and nearby residents are protesting a federal forest-thinning plan stretching from Pine Mountain to Reyes Peak, per my colleague Hayley Smith.

California lawmakers are close to passing a bill that would ban the importation of certain animal “trophies” from Africa. The legislation is designed to protect threatened and endangered species such as elephants, lions and rhinos from hunters who travel overseas to kill them and bring back their severed heads, as Susanne Rust reports for The Times. Susanne talked with a Los Angeles resident who explained why he recently traveled to South Africa to shoot (and eat) an elephant.

AROUND THE WEST

The Navajo Nation has strong objections to a proposed “pumped storage” hydropower project near the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers. Here’s the story from Debra Utacia Krol at the Arizona Republic. In other hydropower news, a bill in California that could have pushed forward the controversial Eagle Mountain project near Joshua Tree National Park was shelved in committee without a vote, although that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s dead. (For more context on Eagle Mountain and “pumped storage” technology, see this story I wrote in March.)

Henrik Fisker is making plans to build and sell an electric SUV inspired by California. What does that mean, exactly? The Fisker Ocean would have a “vegan” interior (no leather) with parts made from recycled materials, an optional rooftop solar panel, and a button that puts the car in “California Mode” by lowering all windows at once. If it turns out to be a pipe dream, it’s a pretty good one. More details here from The Times’ Russ Mitchel.

Back when the Trump administration was deciding which national monuments to shrink, then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke recommended the creation of one new monument: Badger-Two Medicine in Montana. It’s a gorgeous landscape surrounded by national parks and wilderness areas, and it’s sacred to the Blackfeet Nation. President Trump never did make it a monument, but a new bill from Sen. Jon Tester would protect it as America’s first “cultural heritage area,” as Cassidy Randall reports for High Country News.

What do you want to know?

When you think about California’s climate future, what comes to mind? What keeps you up at night, and what gives you hope or gets you excited? What do you want to understand, and what should I?

This newsletter is for you, to help you understand how we’re changing our world and what we can do about it, and I want to hear your questions, concerns and ideas. Email me or find me on Twitter.

ONE MORE THING

Remember that lawsuit I mentioned earlier, where SoCalGas is suing the California Energy Commission?

Here’s a tidbit that didn’t make it into the story. The gas company mentions in its lawsuit that microgrids — standalone energy systems that serve individual facilities or communities when power is out on the larger grid — “may require the reliability and affordability of natural gas fuel.” In other words, renewable energy alone can’t keep the lights on.

That claim caught my attention because the same day SoCalGas filed its suit, San Diego Gas & Electric — which, like SoCalGas, is owned by Sempra Energy — announced it had received funding to upgrade its microgrid in Borrego Springs to 100% renewable energy, as Rob Nikolewski reported for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Which of the sister companies is right? Only time will tell.

I’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.