Boiling Point: How rooftop solar could save Americans $473 billion

This is the Jan. 7, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

With less than two weeks until Joe Biden takes office — and with Democrats taking control of the Senate — the growth of clean energy is poised to accelerate. Even if Congress doesn’t fully embrace the president-elect’s $2-trillion climate plan, there will be plenty of actions his administration can take to support renewable power and put pressure on fossil fuels.

So here’s some food for thought: If Biden’s appointees want to help consumers save money, they might consider devoting a big chunk of their efforts to solar panels and batteries that can be installed at homes across the country.

Critics have long dismissed rooftop solar as a niche product for wealthy homeowners who want to feel good about going green or are looking for security against blackouts. And it’s conventional wisdom among utilities and regulators that large solar farms have an inherent cost advantage over the rooftop alternative because they benefit from economies of scale.

Chris Clack sees things differently.

Clack is a leading energy systems researcher, and to say his latest work caught my attention is an understatement. In a fascinating report released last month, Clack and his coauthors estimated that eliminating nearly all planet-warming pollution from electricity generation would be $473 billion cheaper with dramatic growth in rooftop solar and batteries.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That calculation is based on Clack’s exhaustively detailed model of the U.S. electric grid, which he says includes 10,000 times more data points than traditional models and allows for a better accounting of rooftop solar’s costs and benefits to the grid. The model is such a complex beast that Clack built his own computers to help run the simulations, which can take five days to complete.

But the results come down to simple dollars and cents.

Researchers from Vibrant Clean Energy, the consulting firm Clack founded, looked out to 2050 and projected how electricity costs would change under a national policy requiring emissions to fall by 95%. When they mimicked traditional models that favor large solar and wind farms, they found that consumers would collectively pay $385 billion more for power over the next 30 years. Not an unreasonable price tag for taking a huge bite out of climate change, but still not the preferred direction if we can help it.

But when they optimized for smaller-scale solutions — the thing Clack says his model is uniquely good at — they found the cheapest way to reduce emissions actually involves building 247 gigawatts of rooftop and local solar power (equal to about one-fifth of the country’s entire generating capacity today). In this scenario, consumers would save $473 billion, relative to what electricity would otherwise cost.

Even without strong national climate policy, they found, Americans would spend $301 billion less on energy compared to business as usual, if only utilities and regulators could be prodded or compelled to help people put solar panels on their roofs and batteries in their garages wherever it made economic sense.

I should note that Clack’s research was funded by several pro-solar advocacy groups. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong or biased, just that it’s coming from a different perspective than, say, research supported by a utility company or a gas generator.

“We’re saying something that’s a bit heretical,” Clack told me. “I think we’re getting a different set of answers from the utilities and others because of the way the modeling has been done.”

For some outside perspective, I called Jesse Jenkins, a Princeton University energy engineer whose PhD research focused on the exact types of questions Clack is trying to answer. Jenkins was a lead author on Princeton’s Net-Zero America study released last month, which reached the encouraging conclusion that achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 — the long-term target urged by climate scientists and endorsed by Biden — can be done without increasing energy costs beyond historical levels.

Jenkins told me he’s not quite as optimistic about rooftop solar as Clack is, in part because he’s found that large solar farms are a cheaper way to generate power and that more rooftop solar results in fewer large solar farms. He raised several questions about the precision of Clack’s model, saying it’s incredibly difficult to fully simulate local electrical networks, which vary wildly from city to city, suburb to suburb and rural town to rural town.

Still, the two researchers are mostly on the same page.

While Jenkins and his colleagues didn’t attempt to calculate the optimal amount of rooftop solar on the grid, the amount they assumed would ultimately get built — 185 gigawatts — wasn’t far off from Clack’s 247 gigawatts.

And they both agree we’ll need enormous investments in big solar and wind farms — about 1,500 gigawatts by Clack’s reckoning, and 2,000 to 3,000 gigawatts in the Princeton group’s estimation, supported by massive new transmission lines to carry the clean electrons where they’re needed. To make that happen, America needs to start picking up the pace of development immediately, building much more renewable energy every year than it is today.

“I know there are a lot of folks who don’t study this for a living who have in mind that everybody will have solar on their roof and batteries in their garage, and we won’t need to do all this ugly transmission expansion. And that’s unfortunately not the case,” Jenkins said.

Rooftop solar’s role may depend on how cheap the technology gets. And there’s plenty of room for costs to fall.

Alex Laskey, who founded the energy software company Opower and more recently helped launch the advocacy group Rewiring America, points out that rooftop solar costs much less in Australia than it does here. That’s because U.S. solar installers must spend a bunch of extra money on arduous permitting requirements and other bureaucratic hurdles — and subsequently also on marketing, which is more expensive when you’re selling a costlier product.

“As soon as you make rooftop solar more affordable than grid electricity, the product starts to sell itself,” Laskey said.

Rewiring America released a report in October finding that a national transition to solar-powered, fully electrified homes — with electric appliances replacing gas heating and cooking, and electric vehicles replacing oil-fueled cars — could save the average household more than $2,500 per year. The group sent me California-specific data showing similar results here.

Those savings depend on rooftop solar costs coming down substantially, which is far from guaranteed.

But government policies can help, and here we circle back to Biden. Rewiring America co-founder Saul Griffith, a MacArthur “genius” grantee, said the federal government could support low-cost loans to households that might not otherwise be able to cover the upfront costs of going solar and switching to electric appliances. The Biden administration could also work with local governments to rewrite building regulations and make installation a faster, cheaper process.

Only time will tell what the next four years hold. Clean energy is on the rise, but what that looks like — and whether it happens fast enough to forestall the worst consequences of climate change — is yet to be determined.

For now, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

As California phases out fossil fuels, electricity generation isn’t just getting cleaner — it’s getting smaller and nimbler. And I’m not just talking about rooftop solar, although that’s part of it. My latest story explores how appliances in your home — such as smart thermostats, solar-charged batteries, electric water heaters and electric cars — could help California keep the lights on as part of “virtual power plants.” Utilities are increasing looking to these tools to help avoid a repeat of August’s rolling blackouts.

The lobbyist whose French Laundry birthday party Gov. Gavin Newsom attended is a partner at a lobbying firm that represents a major oil company. Jason Kinney is a friend and advisor to the governor, and his firm represents Aera Energy, a partnership of Shell Oil and Exxon Mobil that has gotten dozens of fracking permits from the Newsom administration over the last year, as The Times’ Taryn Luna and Phil Willon report in an excellent story examining the relationship between the two men.

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?” My colleague Rosanna Xia wrote a wonderful profile of Susan Hansch, who may have done more than anyone to protect the California coast from oil companies, sea-level rise and development. She’s retiring after 46 years at the California Coastal Commission, an agency she’s served since the very beginning.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

This will be the second-to-last edition of Boiling Point during the Trump administration, so let’s see what they’re up to as the clock winds down. The Interior Department finalized a rule gutting protections for migratory birds, which was sought by the oil industry, and the Environmental Protection Agency dramatically limited its own ability to use public health studies to regulate threats to public health. But as L.A. Times columnist Michael Hiltzik notes, a Democratic-run Senate could undo both of those new rules — and other last-minute regulatory changes — with a simple majority vote via the Congressional Review Act.

President Trump vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have banned large-mesh drift net fishing off the coast of California. Here’s the story from the AP’s Darlene Superville. I had never heard of this bill previously, which just goes to show how much stuff is happening all the time. The fishing method can kill dolphins, whales and sea lions and is already illegal in other federal waters.

Dwight Hammond Jr. and his son Steven were convicted of arson and sent to prison for setting fire to public lands. Now the Trump administration wants to give them their grazing rights back, as the Oregonian’s Maxine Bernstein reports. Especially today, as pro-Trump rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol, I couldn’t help but think about the violence perpetrated for years by anti-government “sagebrush rebels” in the West. I’d recommend reading Leah Sottile on this topic if you haven’t already.

AROUND THE WEST

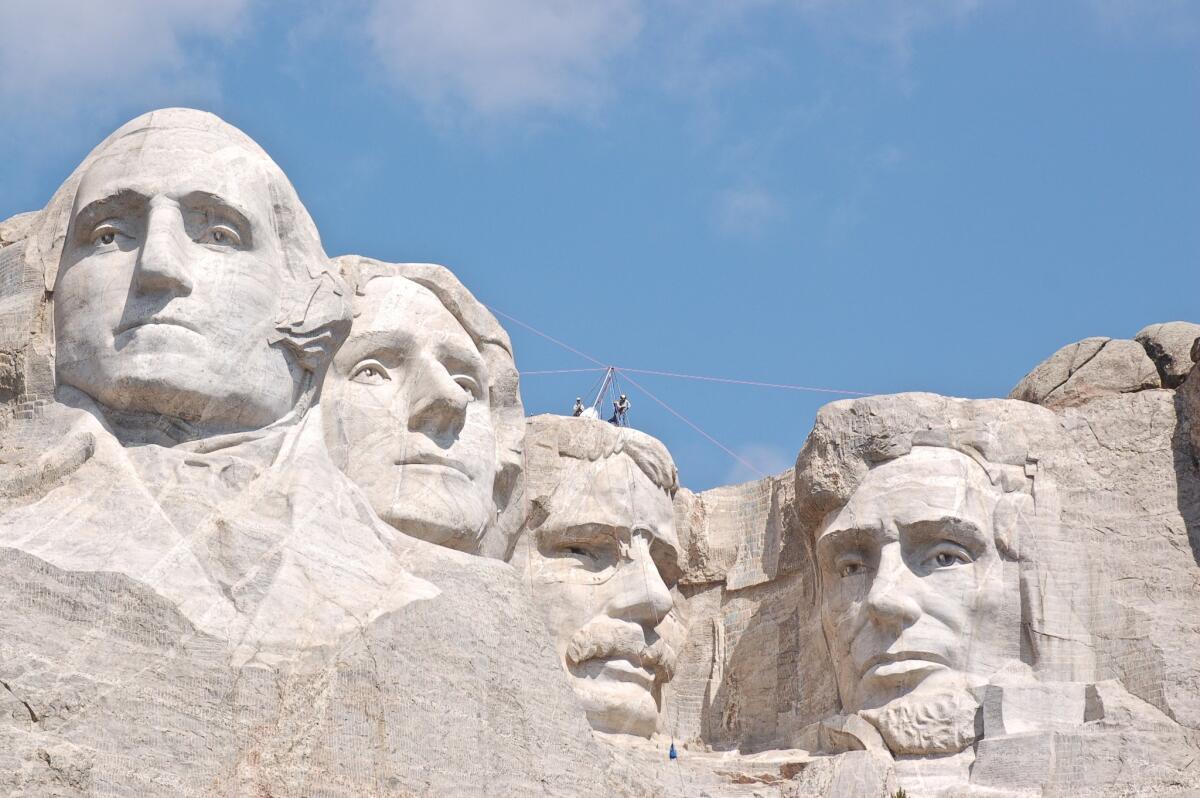

Speaking of violence in the West, Native Americans have been on the receiving end by white settlers for centuries. In a powerful piece for High Country News, Nick Estes writes about the Indigenous movement to take back South Dakota’s Black Hills, where Mount Rushmore was literally sculpted by a Ku Klux Klan leader. Rushmore “came to South Dakota by way of a Southern, white supremacist ideology that blended easily with the West’s sense of Manifest Destiny,” Estes writes.

I wrote last week about the Colorado River, and efforts to get supply and demand into balance as climate change saps the river’s flow. For a far more thorough and deeply reported story, see this piece by the Arizona Republican’s Ian James, who’s one of the best chroniclers of water in the West. He went up into the river’s Rocky Mountain headwaters with photographer Nick Oza to explore the impact of rising temperatures and worsening wildfires, and to learn how farms and cities are trying to adapt.

Should we be panicking over a new Wall Street futures contract that allows investors to bet on water scarcity in California? L.A. Times columnist Michael Hiltzik doesn’t think so. He writes that the futures market “isn’t a harbinger of savage bloodletting over dwindling water supplies,” although he thinks its ability to encourage more sustainable water use will be pretty limited.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Another western coal plant will shut down sooner than planned, adding to the surge of early closure announcements that I wrote about a few weeks ago. Xcel Energy said it will close two coal-fired generators in Colorado in 2027 and 2028 rather than waiting until 2030 and 2036, as Greg Avery reports for the Denver Business Journal. That should help Colorado get closer to its ambitious climate goals, but overall the state still doesn’t have sufficient policies in place, per the Colorado Sun’s Mark Jaffe.

Despite the growing popularity of rooftop solar, two of the biggest installers, Sunrun and Sunnova, are losing lots of money. But their stocks keep rising, with investors seeing strong long-term potential, as Peter Eavis and Ivan Penn report for the New York Times. Many smaller installers are thriving financially, in a business where local firms have some key advantages.

San Diego Gas & Electric says it needs permission to raise electricity rates by 3.3% this year because it was so hot last summer that it paid more for energy than expected. Here’s the story from Rob Nikolewski at the San Diego Union-Tribune.

ONE MORE THING

Occasionally I read something that gives me extreme wanderlust, and as the calendar flipped from 2020 to 2021 it was this story by David Kelly — with amazing photos by Brian van der Brug — about what it’s like driving the 140-mile Mojave Road through some of the most beautiful, rugged and truly weird parts of the California desert. I mean, seriously, check out this red-tailed hawk:

I know 2021 is off to a rough start. But there will be good things to come this year.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.

Also, last week’s newsletter included a quote referencing Willie Horton. It should have referenced Willie Sutton.