Newsletter: Climate lessons from Grand Teton National Park, and the Jewish New Year

- Share via

This is the Sept. 9, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

When last week’s edition of this newsletter sent, I was sleeping in a tent near Paintbrush Divide, a 10,700-foot mountain pass deep within Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park. I would soon awake to a stunning view of Leigh Lake, feeling relaxed and refreshed after three days backpacking through the wilderness. As my friends and I prepared breakfast, we would be joined by a moose just outside our campsite, munching on plants and totally unperturbed by our presence.

A few hours later, we would complete the Teton Crest Trail, celebrating with a selfie and congratulating ourselves for hiking 42 miles and managing not to encounter any bears. I would glance at my email for the first time all week and be pleased to find that the world had not ended. Whatever I had missed, clearly it could wait. After a year and a half of taking hardly any breaks from work during the pandemic, this vacation reminded me that life is an end, not a means.

It also reminded me of all the things worth fighting for.

For example: Hiking through Yellowstone National Park and later the Tetons, I couldn’t help thinking about the “30 by 30” movement, a campaign by scientists and environmentalists to protect 30% of America’s lands and waters by 2030.

Here were some of the most spectacular landscapes I’d ever seen — shooting geysers and bubbling mud pots and steam vents reeking of sulfur, pristine alpine lakes fed by glacial melt, roaring waterfalls above the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Here were vast herds of bison — glorious beasts nearly hunted to extinction but now recovering (and blocking the trail my friends and I were trying to hike). Here was a lone bighorn sheep on Death Canyon Shelf, near the trickling stream that would slake our thirst.

It’s not for me to say whether “30 by 30” is the right strategy for giving animals and plants more space to roam as the planet warms. But we need to do something to secure Earth’s biodiversity. Not only for the sake of preventing extinctions, but for our own safety. A healthy planet is a planet less likely to produce infectious diseases like COVID-19 and spread them to humans.

There’s also the health of our national parks to consider, and the experience of visiting them. While the Teton Crest Trail wasn’t crowded — the park service issues only a handful of permits each day — more accessible spots, such as Old Faithful, were overrun by people. I picked up the local newspaper in West Yellowstone, Montana, and read that Yellowstone National Park had welcomed more than 1 million visitors in July, an all-time record. Grand Teton National Park had also seen its busiest month ever.

The National Park Service has been getting creative, trying out timed-entry reservations at popular parks and launching an app to help visitors avoid crowds, as Katharine Gammon reports for High Country News. I saw one of the agency’s innovations in action: a driverless shuttle known T.E.D.D.Y. (“The Electric Driverless Demonstration in Yellowstone”) that ferries small groups between campgrounds and visitor services in a pilot program to reduce traffic, noise and air pollution. It’s a charming contraption:

Creating more national parks is another popular idea, although there are differing opinions on how much it would help.

In a recent essay for the New York Times, Kyle Paoletta argued that reclassifying national monuments and other protected spaces as full-fledged national parks is “an easy part of the solution” that would draw adventurers to less-crowded spots. Jonathan P. Thompson disagreed, writing in his Land Desk newsletter that designating new parks would result in now-pristine areas being overrun, while already-packed parks such as Arches and Zion would still draw far more people than their ecosystems can handle.

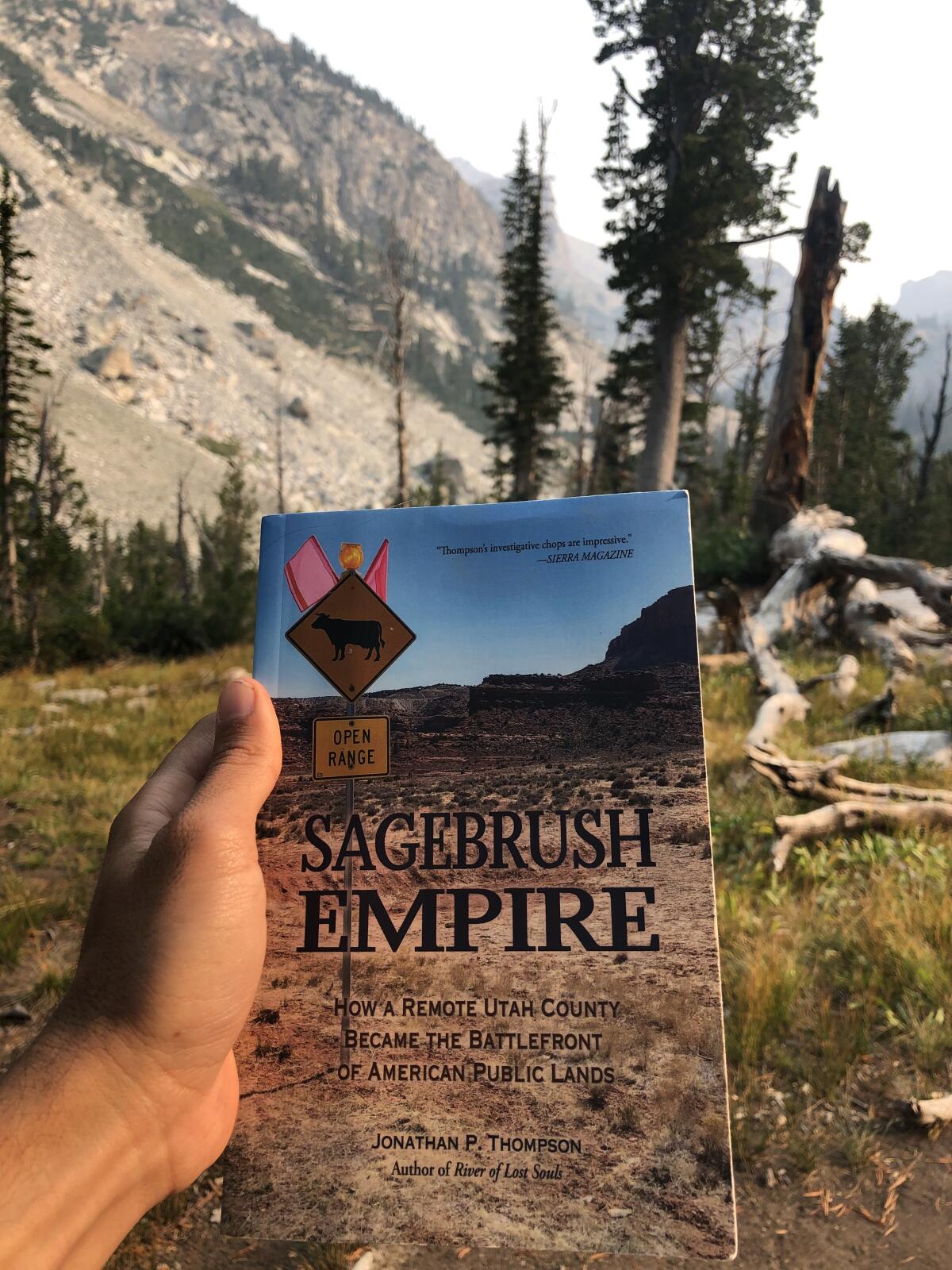

Speaking of Thompson, I started reading his new book, “Sagebrush Empire,” while on the Teton Crest Trail. I’d recommend it to anyone who cares about the West. It’s all about Utah’s San Juan County, home to some of America’s most beautiful scenery (including Bears Ears National Monument) and also a hotbed for “sagebrush rebels” seeking to exploit public lands for profit.

Oil and gas companies have, of course, reaped enormous profits from public lands. And along with other climate polluters, they’ve helped fuel ever-more-intense heat and fires that are blighting our national parks — even when there’s not a pumpjack in sight.

I was warned before arriving in Wyoming that the Teton Range was obscured by wildfire smoke, much of which had blown east from California and Oregon. Suffice to say, I wasn’t pleased — especially after reading about research suggesting that smoke from faraway wildfires may be more toxic than smoke from nearby blazes. I didn’t want to worry about inhaling fumes that could make me sick, and more vulnerable to COVID-19. I didn’t want the sight of the Tetons to make me think about climate change.

Much of the smoke had cleared by the time my friends and I arrived. But the air was still hazy, diminishing the gorgeous scenery. I was sad, but not surprised; in our era of climate catastrophe, there’s no place untouched, no experience unchanged.

I got back to L.A. on Monday, Labor Day, in the midst of yet another heat wave made worse by global warming. As I write this newsletter, the Golden State’s main power grid operator is promoting its latest “Flex Alert,” urging residents to use less electricity Wednesday evening (and also Thursday evening) to stave off blackouts. Over 2 million acres have burned in California this year, my colleague Hayley Smith reports, and the Dixie fire looks like it will become the state’s second-ever million-acre fire.

Against that backdrop, I attended virtual services for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, on Monday night. Rabbi Ken Chasen of Leo Baeck Temple began the service by describing the many ways the novel coronavirus has disrupted our lives.

“If this pandemic has taught us nothing else, it has conditioned us to speak about the future with greater humility,” he said.

Rabbi Chasen also described the last year as “the year that the liturgy of these High Holy Days came alive for us, perhaps more disturbingly than ever: Who shall live and who shall die, who by fire and who by water, who by earthquake and who by plague.”

“If ever these images felt somehow grandly distant, they do no more,” he said.

People ask me all the time how I write about climate change without getting depressed, or how I stay hopeful. This year, as summer turns to fall, I’ve got the vistas of Yellowstone and the Tetons in my mind’s eye, and the rabbi’s words in my ears.

Yes, the world is scary. People are dying in fires and heat waves and hurricanes. The science paints a grim outlook.

But let’s speak about the future with greater humility. Despite the decrees that the Jewish God is supposed to issue at this time of year — who shall live and who shall die, who by fire and who by water — the future is not preordained. It’s not written. We can still stem the climate crisis, whatever that might look like technologically, economically, socially. It’s a choice, not destiny.

And there are so many good reasons to make that choice, from the preservation of our parks to the protection of our lungs.

Yes, humanity getting its collective act together may sound unlikely. But many of us thought the pandemic would have eased by now, just as many climate scientists thought conditions wouldn’t get this bad, this quickly. They were wrong, and we were wrong, and it’s possible to be wrong in the other direction too. Things could get better. We could be underestimating our survival instinct, and maybe even our compassion.

For now, let’s hope for a shanah tovah u’metukah, a good and sweet year. Here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California’s carbon offsets program is wracked with problems, allowing oil refineries and other polluters to keep spewing heat-trapping gases by paying to protect trees that in at least one case had already gone up in smoke. My colleague Evan Halper has a great in-depth piece on what’s going wrong, which includes this extremely defensive response from a state official: “The program has worked exactly as we expected. ... There is nothing untoward. There are no questions of its legitimacy.”

Climate-driven wildfires are emerging as a new threat to the clear blue waters of Lake Tahoe. The world-famous recreation spot straddling the California-Nevada state line was ultimately spared from the Caldor fire, with evacuation orders lifted over the weekend. But haze and falling ash still blanketed the area, reducing the lake’s clarity, The Times’ Tony Barboza and Anita Chabria report. See also these intense photos by Wally Skalij of firefighters straining to protect Lake Tahoe. And if you want to find a home in California with relatively low wildfire risk — or protect your home against fire — Rachel Schnalzer has a helpful rundown.

Climate conditions are bad at Mt. Shasta, a 14,179-foot sentinel standing watch over Northern California. The mountain’s usually abundant snowpack is completely gone, leaving behind bare brown slopes and melting glaciers that are fueling dangerous mudslides, threatening local drinking water supplies. “Flows of volcanic ash also have turned once-green meadows into ghostly gray moonscapes,” my colleague Louis Sahagún writes. Nationally, the Washington Post’s Sarah Kaplan and Andrew Ba Tran did some fascinating analysis and found that nearly one in three Americans live in a county hit by a weather disaster this summer.

AROUND THE WEST

Drought has farmworkers dreaming of escape from California’s breadbasket. My colleague Priscella Vega profiled three women in the San Joaquin Valley who want out of a farm life that has become more unbearable than ever; it’s a beautiful and heartrending portrait, with photos by Tomas Ovalle. Elsewhere in the West, tourism is hurting as Colorado’s largest reservoir drops — mostly because of drought, but also because of intentional water releases to boost Lake Powell and keep up hydropower production, Colorado Public Radio’s Michael Elizabeth Sakas reports. Back in California, officials are coughing up nearly $2 million to help the desert city of Needles drill a new groundwater well after its only good one failed, per The Times’ Ralph Vartabedian.

Air quality in Salt Lake City is already awful because of vehicle exhaust, industry, and dust from the shrinking Great Salt Lake — and now climate-driven drought is making it worse, bringing wildfire smoke from California. The New York Times’ Simon Romero writes about how dirty air could derail the nation’s fastest-growing state. NPR’s Nathan Rott, meanwhile, reports on alarming new research finding that wildfire smoke can get inside our homes too, although air filters can lessen the harm.

While I was vacationing in the Yellowstone region, I picked up a local newspaper featuring an Associated Press story about Idaho lawmakers receiving threatening letters over their votes for a law that could dramatically reduce wolf numbers. The expansion of gray wolf populations is a contentious issue across the West, as Paige Blankenbuehler detailed for High Country News in this wonderfully engrossing story taking us down the Green River and exploring the human barriers to wolf-friendly landscapes.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

By the time next week’s edition of this newsletter publishes, California’s gubernatorial recall election will be over. If you’re still deciding how to vote, check out this L.A. Times Q&A with some of the leading candidates; asked about how to confront drought, they had similar answers (invest in desalination, recycling and more reservoirs). Elsewhere in the realm of California politics, state lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom failed to reach a compromise on bullet train funding, Ralph Vartabedian reports.

Hundreds of thousands of streams, wetlands and other waterways will regain protection as a judge throws out the Trump administration’s interpretation of the Clean Water Act. Here’s the story from the AP’s Suman Naishadham and Michael Phillis.

“Though Manchin’s motivations are often ascribed to the conservative, coal-friendly politics of West Virginia, it is also the case that the state’s senior senator is heavily invested in the industry — and owes much of his considerable fortune to it.” That’s the key takeaway from this piece by Daniel Boguslaw for Type Investigations and the Intercept on Sen. Joe Manchin, the Democrat whose vote could determine whether President Biden is able to sign any kind of significant climate legislation.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

California has quietly settled a lawsuit brought by the nation’s largest gas utility over climate policy. Here’s my latest on the suit filed by Southern California Gas Co., which as I noted a few weeks ago is a subsidiary of fossil fuel giant Sempra Energy. Also check out this piece by MacKenzie Elmer for Voice of San Diego, about gas utility workers at another Sempra subsidiary — San Diego Gas & Electric — who are pushing back against climate policies that they worry would result in their jobs being eliminated.

Los Angeles City Council unanimously endorsed Mayor Eric Garcetti’s goal of 100% clean electricity by 2035. That’s 10 years ahead of California’s current mandate; Jason Plautz has the details at Utility Dive. See also my story from March about the extensive study concluding L.A. could eliminate fossil fuels from its power mix by 2035 without significant economic disruption.

An oil and gas industry group filed for bankruptcy after an appeals court ordered it to pay nearly $2.3 million in attorneys’ fees to the city of L.A. and the Center for Biological Diversity. The court ruled that the California Independent Petroleum Assn. violated an anti-SLAPP law by suing the city and the environmental group over new requirements for oil and gas drilling, Jake Abbott reports for the Sacramento Business Journal. In other words, the court found that the oil and gas association was trying to block the new rules through costly litigation meant to silence opponents — exactly what anti-SLAPP laws are designed to prevent.

ONE MORE THING

I’m going to end this newsletter by asking for your help.

If you read Boiling Point from week to week, you know how much the Los Angeles Times has invested in robust climate and environmental journalism — not only my reporting on energy, but also my colleagues covering water, fire, air quality, the coast, public lands, federal policy, electric cars, the oceans and more. This work isn’t free; it’s made possible by our paying subscribers. If you want us to keep it going, not to mention do more of it — which we definitely want to do! — we need more subscribers.

If our journalism is meaningful to you, and you can afford it, please subscribe to The Times. You can get unlimited digital access for $98 per year, and you’ll be supporting the largest newsroom west of the Potomac River. I’d be very grateful.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.