Trump team rolls back desert protections in bid to boost geothermal energy

- Share via

LONE PINE, Calif. — In step with President Trump’s push for more energy development in California’s deserts, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management announced Thursday it wants to transform 22,000 acres of public land in the southern Owens Valley into one of the largest geothermal leasing sites in the state.

The agency has determined that the aquifer deep beneath the surface of the vintage Old West landscape of Rose Valley, about 120 miles north of Los Angeles, is a storehouse of enough volcanically heated water to spur $1 billion in investments and provide 117,000 homes with electricity.

Yet the decision is sure to set off a new water war in an arid part of the eastern Sierra Nevada that is sprinkled with dormant volcanoes, spiky lava beds and rare species, such as desert tortoises.

The BLM contends it can balance competing interests with its plans to amend Obama-era restrictions on energy development across 22,000 acres in a region it calls the Haiwee Geothermal Leasing Area.

“We believe we can provide additional flexibility for energy development in that area,” Jeremiah Karuzas, the BLM’s renewable energy program manager in California, said in an interview, “while still trying to maintain conservation plans put forward there.”

Karusas said geothermal production has “a relatively compact footprint” with less impact than other energy plants.

But critics believe it marks the beginning of the end of California’s desert protections. During the Obama administration, deals were cut on which lands would be conserved, which would be leased for mining and energy development, and which would be designated for recreation.

Conservation groups led by the Center for Biological Diversity are preparing legal challenges, hoping to prevent access roads, pipelines, drilling rigs and trucks from intruding into the Rose Valley and desert areas, at the expense of their unique plants and animals.

“We thought we had a deal in the California desert,” grumbled Ileene Anderson, a biologist with the Center for Biological Diversity. “Everybody was happy. Nobody sued.”

“Now, the Trump administration and BLM owe us a reasonable explanation — not a political one,” she added, “for rolling back protections we were told would last forever.”

After years of playing third fiddle to solar and wind power, new geothermal plants are finally getting built.

The Obama administration spent eight years and considered more than 14,000 public comments in developing its plan for wind, solar and geothermal projects and conservation. It set aside 3.9 million acres to be permanently protected as National Conservation Lands, including portions of Rose Valley. Another 1.4 million acres were designated areas of critical environmental concern. And 388,000 acres were designated appropriate for commercial-scale renewable energy projects.

In a surprising reversal, President Trump less than a year ago ordered the BLM to reopen study of its Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan and consider shrinking the areas it protects, in turn expanding lands available for commercial-scale wind, solar and geothermal energy production and mining.

In Rose Valley, herds of mule deer seasonally drift between the Sierra Nevada on the west and the Coso range on the east. Springs ooze from the base of lava cliffs. Natural caves scoured by wind and rain overlook rugged habitat for Mojave ground squirrels and other rare species. Beneath cinder cones streaked red and orange, the ground glistens with shards of volcanic glass left by ancient Paiutes making tools and arrowheads.

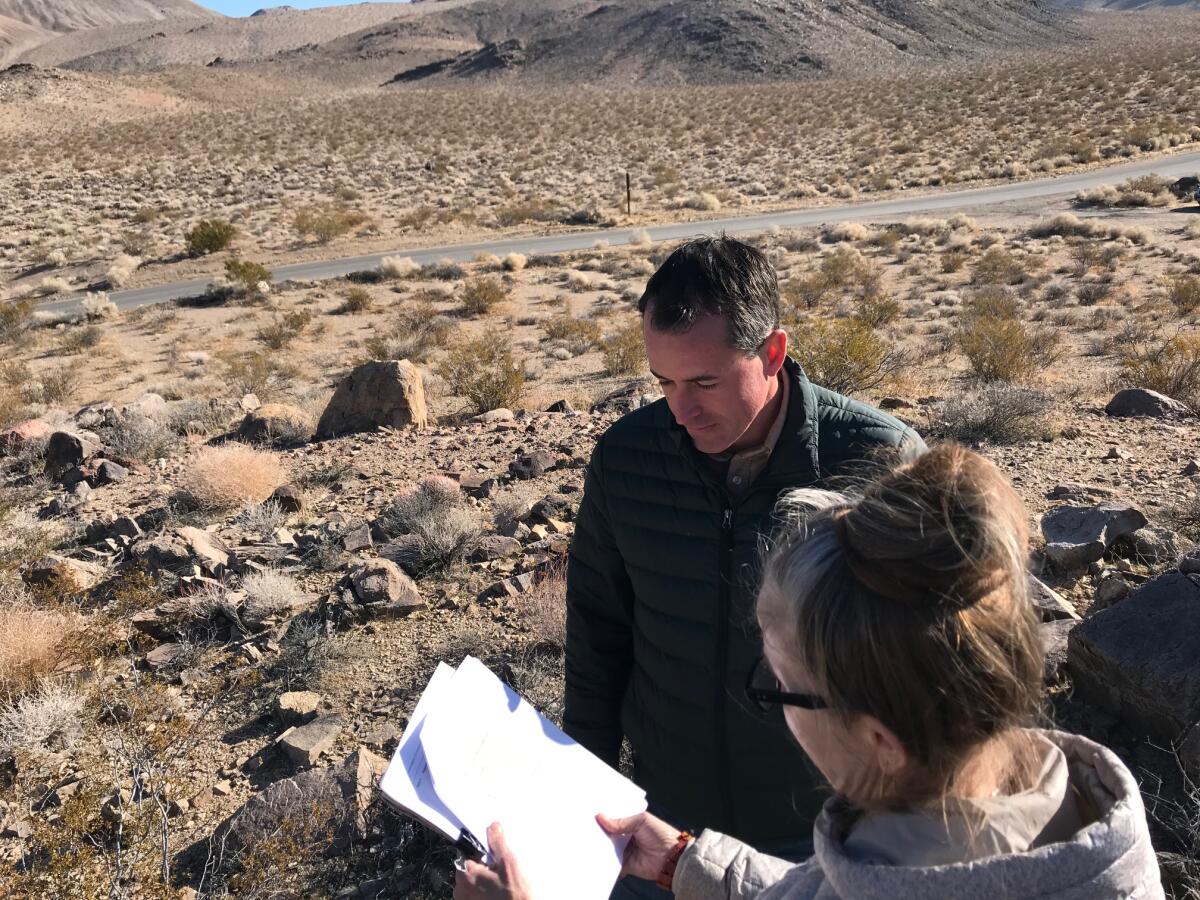

On a recent weekday, environmental activist Frazier Haney stood on a hilltop above the valley and reached out to embrace the panoramic views of the high-desert terrain.

“What worries me most is that the BLM is going back on its commitments to protect this land and its wildlife,” said Haney, deputy director of the nonprofit Wildlands Conservancy. “It’s hard not to see that as an assault on America’s 130-year tradition of protecting public lands, and an attack on Obama’s legacy.”

Linda Castro, assistant policy director for the California Wilderness Coalition, said, “Normally, we’re supportive of alternative energy projects. But in this case, a court will have to decide whether the BLM has the authority to change management rules in lands set aside for conservation.”

The BLM move was cheered by some green-energy advocates, who contend that concerns about environmental damage are exaggerated and remind critics that the power they provide can help the state achieve its climate change goals.

Intrusions of magma at relatively shallow depths beneath Rose Valley make it “literally a hot spot for developing geothermal resources,” said Ian Crawford, a spokesman for the Davis, Calif.-based Geothermal Resources Council, an association that promotes the alternative energy resource.

“We should be working with the environmental community,” he said, “to make this happen.”

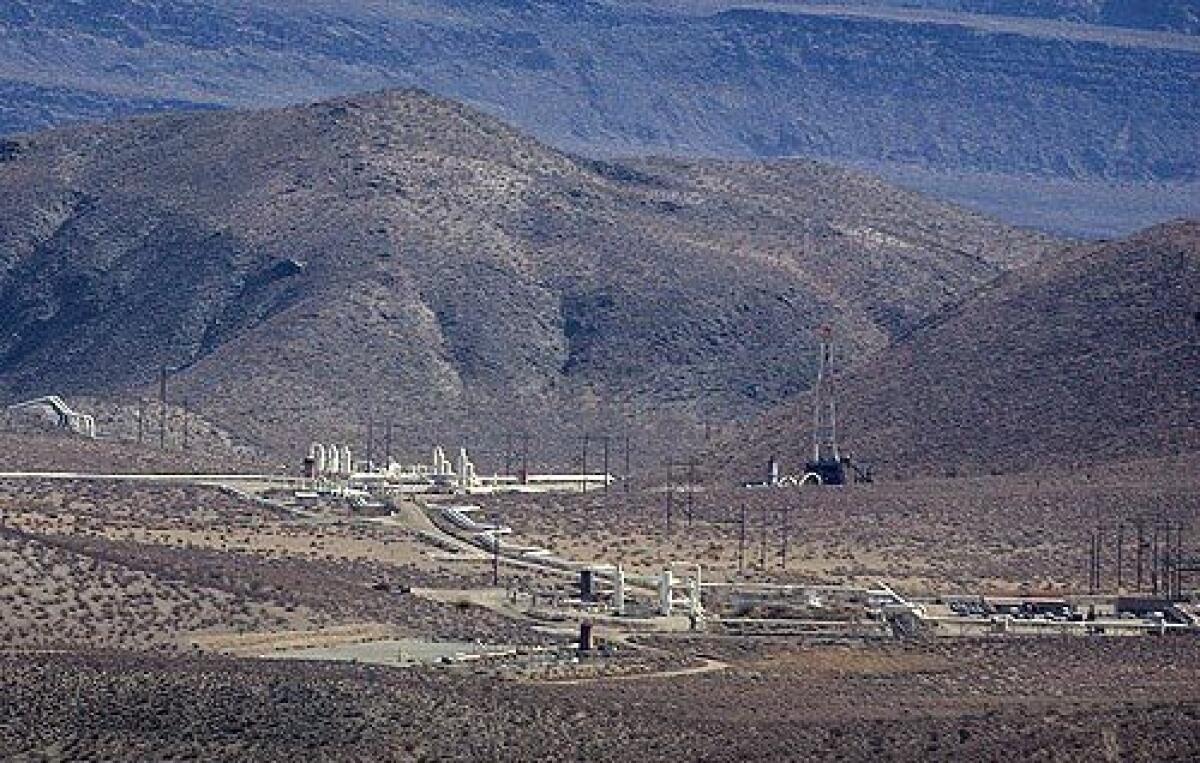

Just east of Rose Valley, on a mountain within the high-security China Lake Naval Weapons Testing Center in Inyo County, Coso Operating Co. has operated four geothermal power plants since 1987. The Coso site, which supplies about 8% of the entire geothermal power in the United States, has generated more than $135 million in property and sales taxes for the county over the past 20 years.

In Rose Valley below, the BLM is currently reviewing three pending lease applications for 4,460 acres of land sought by two U.S.-based geothermal companies, BLM officials said.

If approved, they would add to a surge of interest in solar, wind power and geothermal energy development in California.

A geothermal power company says it can make California’s Salton Sea the first major source of U.S. lithium production.

Elsewhere, energy providers signed contracts this month for electricity from new geothermal power plants in Imperial County near the Salton Sea and in Mono County along the Eastern Sierra. They will be the first geothermal facilities built in California in nearly a decade.

The future, however, remains uncertain in Rose Valley.

“The BLM is making a serious mistake by going back to the days when it favored energy development over conservation on public lands,” Haney said. “This move has only destroyed hard-won trust among stakeholders.”