RIMFOREST, Calif. — High in the San Bernardino Mountains, water seeps from the ground and trickles down the mountainside among granite boulders and bay laurel trees.

Near this dribbling spring, water gushes through a system of tunnels and boreholes, and flows into a network of stainless steel pipes that join together in a single line. The water then courses downhill across 4.5 miles of rugged terrain in the San Bernardino National Forest to a tank, where some is hauled away in trucks to be bottled and sold as Arrowhead 100% Mountain Spring Water.

Local environmentalists say the bottled water pipeline doesn’t belong in the national forest and is removing precious water that would otherwise flow in Strawberry Creek and nourish the ecosystem. After nearly seven years of fighting against the extraction of water, activists say they hope California regulators will finally order BlueTriton Brands — the company that took over bottling from Nestlé last year — to drastically reduce its operation in the national forest.

“They’re sucking out so much water,” said Amanda Frye, one of the leading activists. “Imagine if all the springs were just allowed to naturally flow. We’d have a lot of water in here.”

A trickling mountain creek in the San Bernardino National Forest. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Frye and other bottling opponents hiked with a Times reporter and photographer to sites where water is collected to explain their concerns. If more water were flowing freely downstream, they argue, it would provide a healthier habitat for wildlife, reduce wildfire risk and help replenish groundwater in the San Bernardino Valley.

Frye said it’s outrageous for a company to profit by taking water from public land while Californians are being asked to conserve.

“I have friends that are collecting water in their shower in pitchers,” Frye said, standing next to a pipe that hissed faintly with the sound of running water.

“We’re under a state drought emergency,” she said.

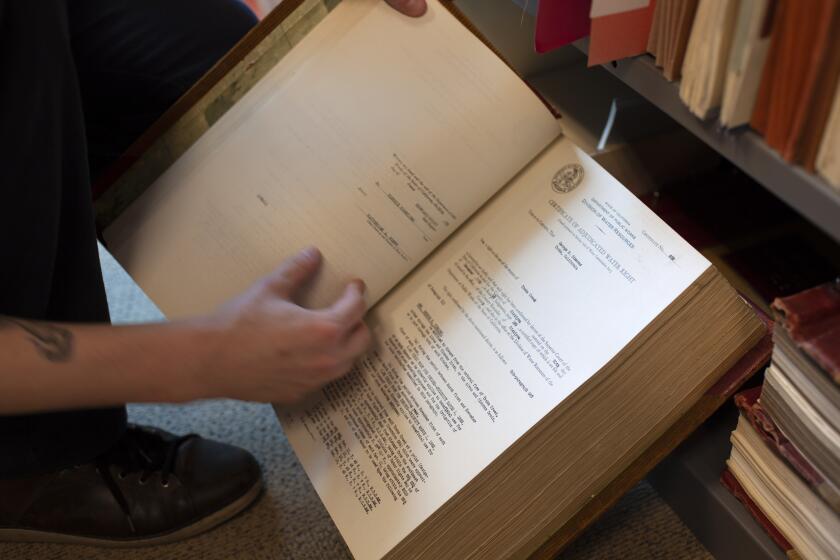

Frye has spent long hours combing through historical archives, and said she believes the company lacks valid water rights. She also thinks the U.S. Forest Service should shut down the pipeline immediately.

“Why is this allowed to happen?” Frye said. “This is our water.”

::

The latest round in the fight over bottled water in the San Bernardino Mountains is playing out in a series of virtual hearings focusing on BlueTriton Brands’ water rights claims.

Last year, California water regulators issued a draft order telling Nestlé, which ran the operation at the time, to “cease and desist” taking much of the water. Staff of the State Water Resources Control Board announced the order after determining the company had been diverting far more water than it had rights to.

Records show about 180 acre-feet (58 million gallons) flowed through the pipeline in 2020. But state investigators concluded the company could only legally divert up to about 7.3 acre-feet (2.4 million gallons) of surface water per year, plus some as-yet-undetermined amount of “percolating groundwater.” If the order is eventually approved by the state water board, the company would be required to immediately stop “all unauthorized diversions.”

BlueTriton Brands — the company’s new name after Nestlé Waters North America was purchased by private-equity firm One Rock Capital Partners and investment firm Metropoulos & Co. — challenged the state’s draft order and requested a hearing.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The series of hearings began last week with the company’s lawyers and the state water board’s prosecution team making their arguments, presenting maps and historical documents, and calling witnesses. Also joining the hearings were Frye and other opponents of the bottled water operation, and lawyers for environmental groups such as the Sierra Club, Center for Biological Diversity and the Story of Stuff Project.

Once Hearing Officer Alan Lilly rules on the draft cease-and-desist order, the matter will go before the state water board for a decision.

The company’s lawyers are arguing the state’s draft order has no merit.

Activists are calling for state regulators to halt the for-profit extraction of water in the San Bernardino National Forest.

“We are confident in our legal and regulatory position,” Larry Lawrence, the company’s natural resource manager, said in an emailed statement. He said the company operates its water-collection system “under valid groundwater rights and consistent with long standing California law.”

The controversy over the bottled water operation erupted after a 2015 Desert Sun investigation revealed that the U.S. Forest Service was allowing Nestlé to continue siphoning water from the national forest using a permit that listed 1988 as the expiration date.

California’s reliance on an antiquated system of recording water rights is hampering the state’s ability to respond to drought, experts say.

The Forest Service subsequently began a review of Nestlé’s permit, while environmental groups challenged the permit in court.

The revelations about Nestlé piping water out of the national forest also prompted several complaints to California regulators questioning the company’s water rights claims, which led to the state’s investigation.

In 2018, the Forest Service granted Nestlé a new three-year permit, with a provision that allowed for two one-year extensions, up to a total of five years. The permit required the company to carry out environmental and hydrologic studies, and included conditions calling for the company to take less water “if monitoring shows that water extraction is impacting surface water flow.”

Over the last several years, while state officials investigated the water rights, the federal “special use” permit has allowed the company to keep using its pipelines, horizontal wells and water-collection tunnels in the mountains north of San Bernardino.

There is no fee for using the water. The Forest Service charges an annual fee based on the acreage of public lands used for the water infrastructure: $1,950 a year.

::

As Frye hiked downhill with her 23-year-old son, Tommy, and two others, the group came to a concrete-block structure containing one of the boreholes, where a steel pipe emerged and ran across a stretch of dry creek bed into the brush.

Bridger Zadina, an actor and environmental activist, squatted and pressed an ear against the pipe.

“You can hear it,” Zadina said. “It’s cool to the touch.”

He said if the water were flowing freely, it would provide for animals such as birds, deer and mountain lions.

The group continued down a dusty slope, clambering on rocks, and arrived at another stone water-collecting structure with a vault-like metal door.

“I can’t get over the ultimate irony of a company draining an area that’s so drought prone,” Zadina said. “This is a national forest. It’s something that should be cared for, for people and not for profit. It just doesn’t make any sense to me.”

Farther downhill, they reached a shady spot among the trees where a trickling spring formed a stream that spilled over a rock ledge.

Standing by the spring, Hugh Bialecki snapped photos with his phone. Bialecki, who leads the local group Save Our Forest Assn., said he thinks these small patches of water show how much healthier the creek could be if the company weren’t piping away so much of the flow.

In the rugged canyon downhill from the springs, Strawberry Creek has continued flowing during the drought.

Bialecki said he’s disappointed that the Forest Service hasn’t shut down the pipeline to study how that would affect flows. He also said the agency should have invalidated the permit when the company was sold.

“We’re really relying on the state water board to do the right thing,” Bialecki said. He hopes the board will enforce the order for the company to stop taking much of the water, and the Forest Service “will finally revoke the permit and just shut down the entire operation.”

A decision by the state water board could come later this year. In their investigation, state officials focused on eight springs in the national forest, where they said the company has three water-collection tunnels and 10 boreholes drilled into the mountainside.

The company says the springs are the namesake source of Arrowhead brand bottled water. Water from Arrowhead Springs was first bottled for sale more than a century ago, and labels on the plastic bottles read “Since 1894.”

The springs in this part of the San Bernardino Mountains, which include hot springs and cold springs, were named after an arrowhead-shaped natural rock formation on the mountainside. Nearby stands the Arrowhead Springs hotel, where the hot springs attracted celebrities in the 1930s and ’40s. The hotel closed in the late 1950s and now stands vacant. The property was purchased in 2016 by the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

Under a decades-old agreement, a portion of the water that flows through the pipeline goes to the Arrowhead Springs property, according to an infographic the company posted on its website. It said water is collected from a “storage silo” at the base of the mountain and trucked to a plant for bottling — a total of 6.4 million gallons in 2020 — and excess water from the pipeline overflows into the watershed.

State water regulators investigated the company’s water rights claims by examining documents dating back more than a century. They told the company in an April letter that the maximum diversion was based on a 1909 contract to take up to that amount each year and deliver it to a bottling plant in Los Angeles.

State officials said the operation has been taking far more than that almost every year since the late 1940s.

In an email, Lawrence said the company does not believe the state water board has “presented any facts or a legal position” to establish that its operations “are unauthorized or that they are causing hydrologic or environmental impacts.”

The company is “a great steward of natural resources” and has been working with the Forest Service providing studies that demonstrate its “success in sustainably managing the springs,” he said.

The company says Arrowhead bottled water comes from 11 spring sites across California, as well as one spring in Colorado and another in British Columbia. The source north of San Bernardino is the only one located in a national forest.

::

As the dispute continues, the Forest Service remains in charge of the company’s permit.

This type of permit isn’t transferable from one owner to another, so the seller submits paperwork and the buyer requests a permit under the new name, said Joe Rechsteiner, the district ranger in the national forest.

“We’re in the process of issuing BlueTriton a new permit,” Rechsteiner said. Like Nestlé’s permit, the new one will be valid until August, he said, with an option to extend it for one year.

In the meantime, Rechsteiner said, studies are continuing “to determine what those impacts are, to the watershed and the resources, from water extraction.”

He said the company, which used to release overflow water only at the bottom of the pipeline, installed a new valve higher in the system after a request by the Forest Service, and now releases some water into the creek in the canyon, downhill from areas where the pipes capture water.

Frye, however, sees the Forest Service’s stance as a dereliction of duty.

“This forest was founded to protect the watershed,” Frye said. And as the country considers approaches for addressing climate change through land protection, she said, “we need to start right here in our own forests.”

If the springs weren’t being tapped, Frye said, the upper portion of Strawberry Creek would be flourishing.

“It’s sick that they’re still taking water,” Frye said as she stood by the mouth of a water tunnel. “It needs to stop.”

From behind a locked metal door, the sound of gushing water filtered out as it filled the 4-inch pipeline and flowed away.

Pasadena’s plan to take more water from the Arroyo Seco has been complicated by the unexpected introduction of hundreds of rainbow trout.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.