(Shutterstock)

You are correct. It is, in fact, extremely unusual to be on hurricane watch in Southern California.

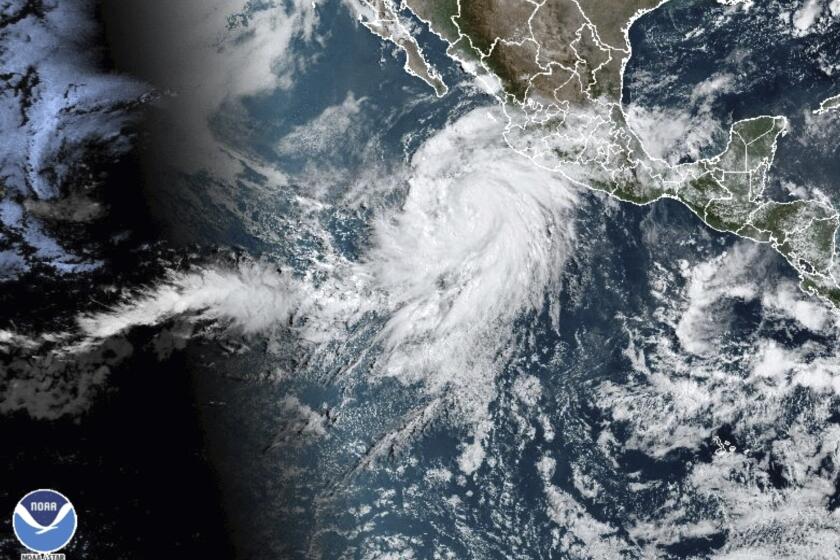

If Hurricane Hilary continues on the trajectory forecasters are currently predicting, it will be the first tropical storm to make landfall in California since 1939, and only the second one to do so since the 19th century.

If this seems like a worrying development to you, one in a string of recent climate-related disasters that seem to portend the arrival of a deeply unpleasant future, you are right about that as well.

And the people who have spent careers thinking about climate change and its likely consequences, who have read the papers and reviewed the models and warned about these potential catastrophes for years — they’re worried too.

For at least the last 165 years, three conditions have kept California hurricane-free, experts say. So what’s changed to make Hurricane Hilary possible?

It’s been 35 years since an explicit reference to climate change first appeared on the front page of a U.S. newspaper, after James Hansen, then director of NASA’s Institute for Space Studies, testified before the Senate that “the greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.”

In the decades since, the effects of climate change have loomed ominously in the distance like the due date of an unpayable mortgage.

But 35 years is enough time for a mortgage to come due, for children to grow up and have children of their own, and for the long-feared consequences of a warming world to become reality.

For climate scientists, it doesn’t feel good to be proved right.

For the record:

1:18 p.m. Aug. 20, 2023An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Thompson Rivers University was in Edmonton, Canada.

“I used to think, ‘I’m concerned for my children and grandchildren.’ Now it’s to the point where I’m concerned about myself,” said Mike Flannigan, a professor of wildland fire at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, Canada.

The Times spoke with several researchers and climate experts about how the recent string of record-breaking, precedent-setting events feel to them. Their comments have been lightly edited for clarity.

‘There’s just too much’

Daniel Swain is a UCLA climate scientist who studies how climate change affects extreme weather events.

This seemingly constant onslaught of extremes, unprecedented weather and climate events — yes, it is different.

Yes, extreme weather disasters happened previously. But we really are seeing a pretty dramatic escalation. It’s gotten less coverage, but the majority of the population of the northwest territories of Canada were evacuated last night [Wednesday] because all of the major settlements are threatened by separate fires. All of them.

It’s an example of how there is now so much going on that it is difficult even to digest it all. There’s just too much. It’s everything everywhere all at once when it comes to extreme climate events this year.

It’s everything everywhere all at once when it comes to extreme climate events this year.

— Daniel Swain, UCLA climate scientist

The amount of global warming we’ve seen is remarkably close to median projections for where we would be at this point. But is the increase in certain kinds of extreme events — and in particular the societal and ecological effects of those increasing extreme events — greater than had been predicted? It’s fair to say the answer is yes.

At this point, every unprecedented extreme heat event has a human fingerprint on it. It would be extraordinarily unlikely for a study to come out and say, “Oh, amazingly, this is a unique heat wave in that it wasn’t made worse by climate change.” Good luck with that. Same thing with really extreme precipitation events. And increasingly, in many places, the same thing is true for things like wildfires.

‘Climate change denial will cost us more and more lives’

Craig Smith is an oceanographer at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He specializes in deep-sea ecosystems, whose fragile natures and slow rates of recovery leave them particularly vulnerable to climate change.

All these climate-related catastrophes occurring in quick succession this year are extremely worrying! They drive home the point that climate-enhanced catastrophes are real and accelerating, heightening the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adopt realistic mitigation strategies as quickly as we can.

These catastrophic events, such as the Lahaina fire, really drive home the monetary and human costs that will result from climate inaction. Delaying investments in sustainable energy and climate adaptation (such as coastal retreat in response to sea-level rise) is penny-wise but immensely pound-foolish. Climate change denial will cost us more and more lives.

‘We’re in uncharted territory. And that’s scary’

Mike Flannigan is a fire scientist at Thompson Rivers University.

Things are crazy. We’re in uncharted territory. And that’s scary. Frightening.

I’ve been doing this for over 40 years, and our models of temperature increases have been pretty darn good. But the impacts are more severe, frequent and intense than I expected. Things are happening, in terms of impact, much more rapidly than I expected.

It was always like, “Well, yes, I’m really worried about 30, 50 years from now.” Now, I’m worried about what’s going to happen next year, let alone the next 10 or 20 years.

I’m worried about what’s going to happen next year, let alone the next 10 or 20 years.

— Mike Flannigan, a fire scientist at Thompson Rivers University

I hope this year is a turning point, but I’ve been disappointed before. A colleague and I wrote a paper in the late ‘90s that said, “Urgent action is needed now to deal with climate change.” I still give talks and at the end I often say, “Urgent action is needed on climate change.” But I’m getting bloody tired of saying this, because we’re not doing enough.

‘Climate action should be viewed as an act of survival’

Jonathan Parfrey is executive director of Climate Resolve, a Los Angeles nonprofit that works toward equitable climate solutions.

People are finally waking up to the reality of climate change. Unfortunately, due to the phenomenon of climate inertia — the massive additional energy that’s been absorbed by the oceans — the die is cast. Our future will grow even hotter.

Climate activism should not be considered an altruistic endeavor. Instead, climate action should be viewed as an act of survival, a necessity.

This moment is a strange mix of grief and hope. On the one hand, I know how precarious our situation is. On the other, we have the tools and ideas, if put into action, that can make a world of difference.

Hurricane Hilary is moving toward Southern California. Here’s how to prepare and stay safe before and during the storm, heavy rain and potential flooding.