California is moving to outlaw watering some grass that’s purely decorative

Outdoor watering accounts for roughly half of total water use in Southern California’s cities and suburbs, and a large portion of that water is sprayed from sprinklers to keep grass green.

Under a bill passed by state legislators this week, California will soon outlaw using drinking water for some of those vast expanses of grass — the purely decorative patches of green that are mowed but never walked on or used for recreation.

Grass covers an estimated 218,000 acres in the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s six-county area. Nearly a quarter of that, or up to 51,000 acres, is categorized as “nonfunctional” turf — the sort of grass that fills spaces along roads and sidewalks, in front of businesses, and around parking lots.

This unused grass covers an area roughly 12 times the size of Griffith Park. By eliminating this grass and replacing it with landscaping that fits Southern California’s arid climate, the district estimates the region could reduce total water use by nearly 10%.

“That will make a big dent in the water that’s currently wasted on outdoor water use,” said Adán Ortega Jr., chair of the MWD board.

Water agencies that supply cities along the Colorado River are pledging to boost conservation and target ‘nonfunctional’ grass to address the water shortage.

Ortega said the legislation is overdue.

“Wasteful outdoor irrigation is a major challenge to our ability to adapt to climate change,” Ortega said.

The bill was passed by the state Senate in a 28-10 vote Monday and is now awaiting Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature.

The legislation prohibits using drinking water for purely decorative grass along roads, in medians and outside businesses and in common areas of homeowners associations.

The bill, AB 1572, was introduced by Assemblymember Laura Friedman (D-Glendale). It outlaws the use of potable water for nonfunctional grass at commercial, industrial, municipal and institutional properties.

The ban will take effect in phases between 2027 and 2031. The legislation includes exceptions for grass in sports fields, parks, cemeteries, areas used for activities, and other “community spaces.” Also exempt are areas where grass is irrigated with recycled water.

“It’s a no-brainer. It’s grass that you look at but never use for anything,” Friedman said. “It means moving to things like natives and drought-resistant plants, which by the way look gorgeous.”

Friedman said that at her home, for example, she ditched nonnative ivy years ago and now has a flourishing native garden with poppies, lupines, fragrant salvias and oak trees.

While the legislation outlaws purely decorative grass in most common areas of homeowners associations, it won’t affect residential lawns.

Grass outside apartment complexes, which originally was included in the bill, was removed from the legislation after some city officials and managers of water agencies raised concerns about how they would enforce the restrictions, and about the costs for low-income communities.

California water regulators have banned the watering of decorative ‘nonfunctional’ grass at commercial, industrial and institutional properties.

The legislation will make permanent a measure that California water regulators adopted last year during the drought — and readopted for another year in May — banning the use of drinking water to irrigate nonfunctional grass at businesses and institutions that isn’t used for recreational or other community activities.

In adopting the water-saving measure, California is following Nevada’s lead. The Nevada Legislature in 2021 passed a law that bans watering purely decorative grass along streets, on medians, at homeowners associations, apartment complexes, businesses and other properties starting in 2027.

The bill is an important step in working toward California’s water goals, said Heather Cooley, director of research for the Pacific Institute, a water think tank in Oakland.

“As we’re facing climate change, as we’re facing continued growth, we have to be smarter about how we use water,” Cooley said. “And so taking out these grass areas that no one is using is really a smart move to prepare our communities for the more variable and uncertain climate that we are now facing.”

She said the legislation also will help cities move toward the state’s planned conservation targets, which in the coming years will require urban suppliers to have water budgets and begin achieving efficiency standards.

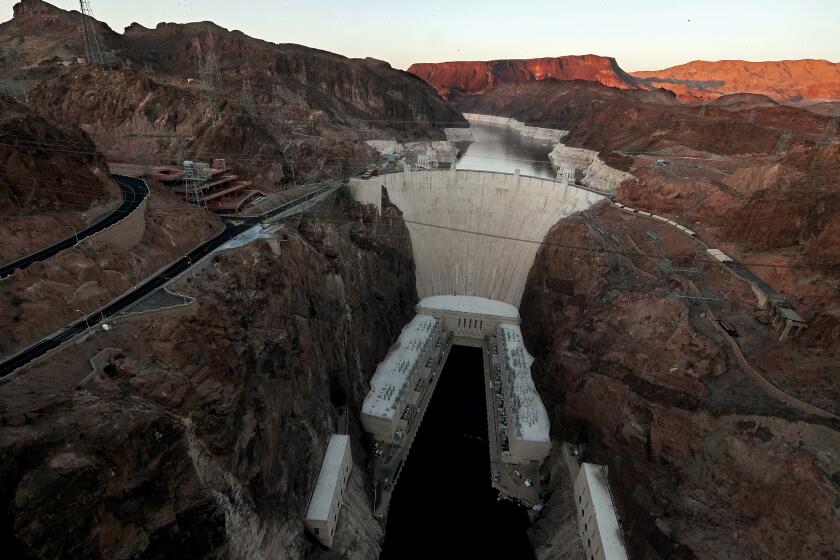

The push to use less water on grass in cities and suburbs has been driven partly by the chronic shortages on the shrinking Colorado River, where reservoirs have reached low levels in recent years, prompting negotiations on plans for reducing water use. Leaders of water agencies have also been discussing ways of achieving water savings in agriculture, which consumes roughly 80% of the river’s water, a large portion of it for alfalfa and other cattle-feed crops.

In cities across the West, areas with unused grass have become a major target for urban water managers as they look for ways to quickly and permanently reduce water use. Some officials have been talking about nonfunctional turf so much that they abbreviate it with the acronym “NFT.”

The efforts to move away from grass also reflect a shift in aesthetics and values, linked to growing scarcity and simple economics. Where once it might have seemed acceptable to line suburban streets with lush landscapes reminiscent of English estates, there is now widespread agreement that it doesn’t make sense for cities to pump water long distances and treat it to drinking water standards — only to spray it on grass that serves no real purpose.

Citing global warming, California Gov. Gavin Newsom has unveiled a new water strategy to conserve, capture, recycle and desalinate supplies.

Last year, the leaders of 30 water agencies that supply cities from Denver to San Diego signed an agreement setting a goal of removing 30% of the existing nonfunctional grass — and replacing it with “drought- and climate-resilient landscaping,” while also maintaining trees.

Conservation advocates have touted various benefits: eliminating unneeded grass not only saves valuable water and reduces delivery costs, but also cuts down on the energy used to pump and treat water.

The bill’s timeline will outlaw using potable water for nonfunctional grass at many properties owned by local governments starting in 2027, followed by commercial and industrial properties starting in 2028, and common areas of homeowners associations in 2029.

The legislation allows local agencies in disadvantaged communities additional time beyond 2031 if necessary to secure state funds to pay for replacing turf with low-water-use landscaping. It also offers flexibility for special circumstances, saying the State Water Resources Control Board may postpone a deadline for up to three years in the event of “economic hardship, critical business need, and potential impacts to human health or safety.”

The bill was sponsored by the Natural Resources Defense Council and Heal the Bay, and the Metropolitan Water District joined the groups as a co-sponsor.

After several revisions, the bill was supported by the Association of California Water Agencies, which represents about 460 public water suppliers.

California is moving forward with new water conservation rules that would require some suppliers to make cuts of 20% or more by 2025.

Cash rebates are available in Southern California and other parts of the state to help property owners with the costs of taking out grass and putting in landscaping that uses less water.

The MWD has a turf replacement program that pays a base rebate of $2 per square-foot of grass removed and replaced with water-efficient landscaping. The rebate is available to homeowners as well as businesses and other property owners. Some of the MWD’s 26 member agencies, including cities and other water suppliers, offer additional rebates, in many cases $1 but in some areas up to $3 per square-foot of lawn removed.

In June, the MWD received a state grant to increase the district’s base rebate to $3 for commercial, industrial and institutional properties, said Rebecca Kimitch, a spokesperson for the agency. Officials expect to make the higher rebates available starting later this year, and are also seeking funds from the federal government to support its rebates for grass removal.

According to the district, the rebates paid out to date have already led to the removal of more than 4,500 acres of grass, saving enough water to supply more than 60,000 average homes.

Studies commissioned by the district have found that for every 100 homes where customers took out grass using a rebate, an additional 132 nearby homeowners were inspired to get rid of their lawns without receiving a rebate — something the district’s managers have called “the halo effect.”

Last year, the district’s board passed a resolution urging cities and water agencies across Southern California to enact local ordinances prohibiting the use of potable water for nonfunctional grass outside businesses and along roads, as well as in new home construction.

“There’s a huge opportunity there,” said Adel Hagekhalil, MWD’s general manager. “If it’s not being used by somebody, it’s just wasting water. And water is so valuable.”

Another bill introduced by Friedman, AB 1573, would have prohibited nonfunctional grass at new or renovated non-residential developments, and would have required more native plants for those properties. Friedman said the measure was intended to help the state’s struggling ecosystems and give a boost to butterflies and other pollinators.

But amendments adopted in the Senate Appropriations Committee would have weakened the measures, including by allowing nonnative plants. And Friedman responded by shelving the legislation.

Another bill, SB 676, which the Assembly passed on Tuesday, empowers cities and counties to ban or restrict the installation of artificial turf on residential properties — something they were prevented from doing under previous legislation that was adopted in 2015.

Supporters of the bill, which was introduced by Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica), said artificial turf poses significant environmental problems. They pointed to research showing that microplastics from artificial turf end up washing into streams and the ocean, and that harmful PFAS chemicals have also been found in artificial turf.

The measure changes the law to specify that cities and counties may not prohibit the installation of drought-tolerant landscaping “using living plant material,” but may outlaw artificial turf.

Another approved bill, AB 1423, bans the manufacturing and sale of artificial turf containing PFAS chemicals. That bill is also awaiting the governor’s signature.