GIANT ROCK, Calif. — For some, the enormous boulder in the Mojave Desert is a sacred site. For others, it’s a gathering spot to camp, climb, off-road or party.

On a recent afternoon, the aptly named Giant Rock is the first stop on a tour from a UFO convention whose guides tout it as the place where, in 1953, extraterrestrials visited a man and instructed him to build a time machine that is now one of the area’s main tourism draws, helping to spawn a movement of “contactees” who still periodically gather there.

A woman kicks off her shoes and buries her feet in the sand. Some wrap their arms around the rock’s worn face or press their faces into its sun-warmed surface.

“This is a very big landmark for ufology,” says Julio Barriere, 75, as he lights sticks of palo santo. The retired actor traveled from Queens, N.Y., to attend the Contact in the Desert Convention. He carries a bag with crystals, a singing bowl and a tuning fork designed to activate the pineal gland, which some believe can enhance telepathic abilities. “If there was a history book of this stuff, you would put Giant Rock in it.”

But the seven-story rock on federal public land has also become a tinderbox of tensions over who gets to enjoy this patch of desert, which has rapidly gentrified since the COVID-19 pandemic. There’s no signage to inform people of its beloved status. Its face is often splashed with graffiti. Unsanctioned concerts and parties have left it littered with trash and human waste. And recently, troublemakers have been menacing volunteers who try to clean it up.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

“There’s some aggression that’s been coming to a head these past six months,” says Karyl Newman, an artist who has been organizing community cleanups at Giant Rock since 2016. She raises her voice over the buzz of a pressure washer that’s blasting spray paint off the rock’s massive face. In its shadow are the mangled remnants of a folding table.

The night before, a group of kids had driven through her campsite, tied the table to their truck and dragged it around until it broke apart, she says.

And it’s not the first time: During a cleanup campout a couple of weeks ago, someone fired a shotgun, swore and called the group hippies, Newman says.

“I do think that there is this kind of territorialism,” she says, noting that in the most recent incident, the kids yelled at the volunteers to go back to Los Angeles. Newman lives in nearby Yucca Valley.

When a fellow volunteer tried to reason with them, she adds, “They were like, ‘This is our rock. You don’t need to be here.’”

Giant Rock isn’t on the way to or from anywhere.

To reach it, visitors must drive a couple of miles down one of several washboarded sand roads, taking care not to get stuck in a soft drift or to veer onto an offshoot that will transport them deep into the desert backcountry of boulder-studded mountains north of Landers.

And yet the charismatic hunk of granite has been drawing all kinds of people for centuries, if not millennia. Located on the ancestral land of the Serrano, it’s reputed to be a sacred site for Indigenous groups that lived in and traveled through the area.

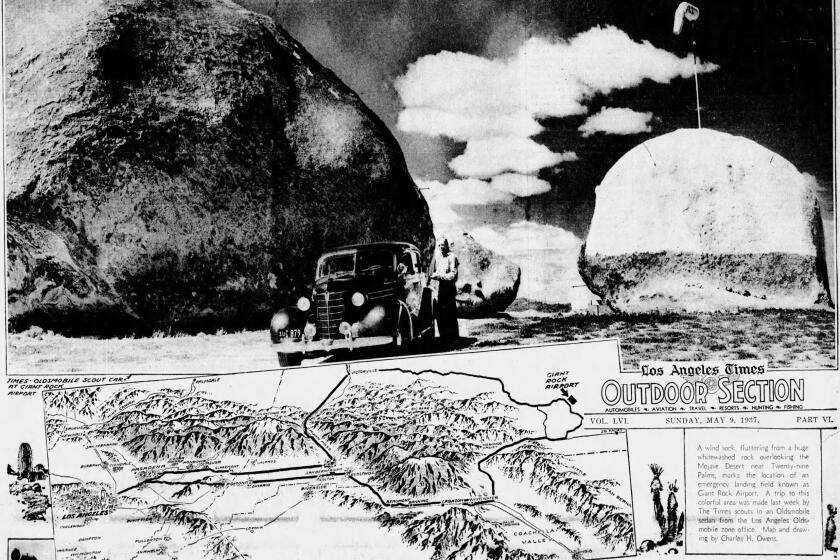

In 1932, prospector Frank Critzer started living under the rock, reportedly using dynamite to excavate a living room and bedroom and constructing a windowed wall beneath the overhang. He dug out roads and built an airport, telling a Times reporter that he hoped to open a winter resort on site.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

But as World War II ramped up, Critzer and his backcountry landing strip came under scrutiny from law enforcement. In 1942, he died in an explosion as a trio of Riverside County sheriff’s deputies sought to question him about some local thefts. News reports say Critzer detonated dynamite he stored beneath the rock, although some suspect the explosives went off when a deputy lobbed a smoke or tear gas grenade inside.

A new tenant soon moved in. George Van Tassel had become acquainted with Critzer — and enamored of Giant Rock — after helping to fix Critzer’s Essex at his uncle’s repair shop in Santa Monica years before. He relocated there with his family, taking over operation of the airport and opening a restaurant, the Come On Inn, where his wife, Evelyn, cooked hamburgers and baked apple pie.

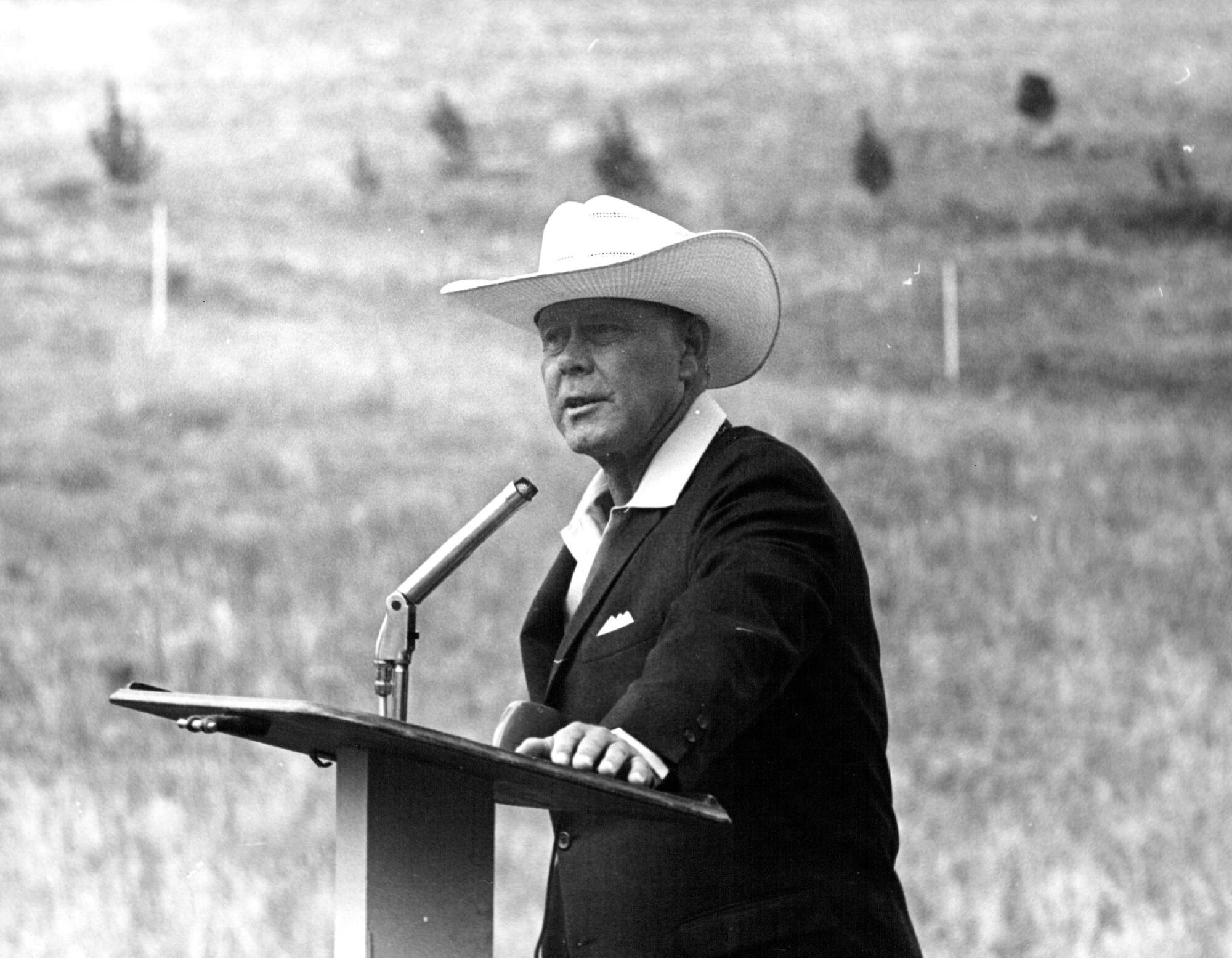

By then, Van Tassel had made a career in Southern California’s booming aviation industry, working as an engineer and test pilot for companies that included Douglas, Hughes and Lockheed Martin. But his beliefs belied his sober, dark-suited image. In the rooms beneath Giant Rock, he began conducting weekly group meditation sessions in which he claimed to channel messages from extraterrestrials.

One night in 1953, Van Tassel reported being awakened by a being from Venus who levitated him aboard a spacecraft and gave him a formula to build an antigravity time machine that could inhibit aging. The being, Solgonda, reportedly wore an amulet that received power from Giant Rock and the surrounding boulders, helping to fuel the site’s reputation as an energetically significant place, a kind of portal between worlds.

Van Tassel began to market the site as a different kind of resort — one where like-minded people could gather to discuss otherworldly beliefs without fear of ridicule or persecution and, perhaps, even hear messages from other planets. He held yearly spacecraft conventions that drew thousands of attendees to Giant Rock, during which he solicited donations for his machine.

Here’s a timeline of key events at Giant Rock, a landmark north of Landers, Calif., that attracts seekers, partiers, conservationists and, according to some, extraterrestrials.

In 1957, he broke ground on what would eventually come to be known as the Integratron, a dome-shaped building of laminated plywood designed to have no metal, including screws or nails. It was intended to one day act as a sort of electrostatic energy generator capable of recharging people’s cells like batteries. Howard Hughes, Van Tassel’s friend and former employer, was a major backer.

In fact, Van Tassel’s enterprise quite literally put the town of Landers on the map, said Justin Merino, vice president of the Morongo Basin Historical Museum. Its namesake, Newlin Landers, owned an L.A. aviation parts business and was fascinated with tales of Van Tassel’s exploits. He flew into Giant Rock Airport and befriended Van Tassel, Merino said.

Landers then gathered a handful of fellow flying enthusiasts and convinced them to homestead nearby, Merino said.

“That’s how Landers came about,” he said. “The alien theme and Giant Rock definitely play a huge part of what Landers is.”

Van Tassel died in 1978 with work on the Integratron incomplete. But the otherworldly mystique he lent the town endures, although it tends to be promoted tongue firmly in cheek. Residents jokingly call themselves “Landroids.” Next to the sign welcoming visitors to town is an art installation featuring the silhouette of a flying saucer, a classic bulb-headed alien peering from each window.

1

2

1. Eric Rankin, a guide from from Contact in the Desert, plays sine wave tones for visitors on the second floor of the Integratron. “It’s the world’s most perfect acoustic dome, almost like being inside a real musical instrument,” Rankin said. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 2. The Integratron today hosts sound baths and spiritual healings. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Giant Rock and the Integratron, now a privately owned venue that can be visited for sound baths or rented for spiritual retreats, continue to be the town’s main draws, along with an exotic orchid farm. There’s little other commerce: a liquor store, a thrift shop and the museum, located in Newlin Landers’ former home, which often fields calls from production companies that want to peruse its archives for documentaries on extraterrestrials.

Still, Merino said, “I don’t think the residents are sitting here waiting for the second coming of the UFOs to take us all away. If anything, the community is more concerned about the damage done to the rock with the graffiti.”

Overseen by the federal Bureau of Land Management, Giant Rock is a designated off-road area. People can camp there for up to two weeks at a time, but there are no facilities. Some pack out their trash; others leave behind broken glass, debris from fires and shotgun shells from target shooting. The secluded spot attracts illegal dumping.

The rock is studded with more than 80 pieces of climbing hardware, according to Newman, although she says some local rock climbers recently agreed to remove some of it.

And Giant Rock has long served as a spot to party. In 1996, 15-year-old Lucas Bielat died beside a campfire during what authorities described as an impromptu rave. A local aspiring musician was later convicted of involuntary manslaughter for providing the teen with a fatal quantity of homemade GHB.

Amboy has been beset by a series of crises that stretch back more than half a century. But owner Kyle Okura hopes to turn it around. No less than his father’s legacy is at stake.

These gatherings have in recent years included unsanctioned large-scale events like generator shows and dance parties whose organizers sell tickets or charge cover fees. One group left behind makeshift toilets, Newman says, although they eventually came back for them after they were shamed on social media.

Those who frequent Giant Rock say it’s rare to see a ranger or officer. The BLM’s Barstow field office, which manages the site, oversees 2.7 million acres of public land in two counties.

Still, the BLM supports the community cleanups, says Park Ranger Art Basulto, who came to the recent event armed with tools, trash bags and water.

Contact in the Desert melds a fascination with Ufology, esoteric spirituality, government conspiracy, alt-celebrity culture and a bit of self-awareness.

Patty Domay, a proud Landroid who volunteers with multiple conservation groups, has a couple of choice words to describe the vandals: “A bunch of young hoodlums,” the 83-year-old says as she drags a magnetic sweeper across the sand to catch nails from burned-up pallets.

Nearby, volunteer David Walsh ducks beneath Giant Rock to swig ice water in the shade. He’s been coming here for so long that he used to eat pie and play shuffleboard at Van Tassel’s restaurant, although he declines to give his age. (“Some things we get to keep,” he says.)

“It’s a wild and crazy place,” Walsh says as the morning warmth gives way to afternoon heat. “I got to go into the rock, too. There was a piano down there, and lots of books.”

He recalls how the military would land “all kinds of weird stuff” on Van Tassel’s airstrip, how 5,000 people might show up to see speakers give addresses from a makeshift stand on the sand at one of his conventions.

Even if you don’t consider its history, the rock’s size alone makes it a worthy attraction, he says, noting that it was reputed to be the largest freestanding boulder on Earth until a piece cleaved off in 2000. “It’s the biggest pebble on the mudball.”

Like everything else about Giant Rock, the split was intensely mythologized, with some saying it fulfilled a prophecy relayed by a South Los Angeles spiritual healer and others attributing it to damage from the large bonfires that are often built beneath it.

Much else has changed since Walsh’s childhood, with the pace of transformation intensifying during the pandemic. Landers saw a massive influx of new residents as hordes of city dwellers, untethered from their offices, sought solace in its starry skies and sandy hills.

Danielle Wall has transformed how locals interact with rattlesnakes. Her work has earned her a front-row seat to reshaping of California’s High Desert.

Some became residents; others flipped properties or converted them to short-term vacation rentals. Home values rose faster than anywhere else in California, pricing out locals. Complaints of absentee landlords rose. A company began selling stickers that read, “Go Back to L.A.” They aren’t an uncommon sight on bumpers across the Morongo Basin.

Some have posited that the tensions at Giant Rock may be fueled, in part, by the same kind of backlash.

“This was just different cultures merging, and one being way more endowed with resources than the other,” says David Gadsden, 50, who purchased a 5-acre plot about a mile from Giant Rock roughly five years ago and maintains it as a getaway and nature preserve. “So you can imagine that locals are like, ‘We’re getting taken over.’”

Most are supportive of the cleanups and many participate, he says. But a small group seems to see Giant Rock as an isolated place to blow off steam, a no-man’s land where they’re entitled to do whatever they want.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That’s where Karyl Newman’s work comes in. The 53-year-old director of nonprofit Positional Projects, which coordinates with artists to spotlight neglected historic sites through installations and events, is drawn to Giant Rock precisely because it’s the nexus of so many diverse stories.

She began collecting those tales, going so far as to travel to Kansas to interview Critzer’s relatives, and then sharing them while volunteers clean up. She calls these events stories and stewardship sessions.

And the public education efforts appear to be paying off. By the end of the recent cleanup, about 20 volunteers had collected more than 520 pounds of trash and removed more than 800 square feet of graffiti. But they no longer need a dumpster to haul out all the garbage as in years past, Newman says.

“These stories are really interesting,” she says. “I think we can share them and other people can build their own appreciation for the site and all the different things that happened there and be inspired to clean it up.”

She recalls that after one cleanup, she met an Indigenous healer who had traveled from out of state to perform a ceremony there with others. As it came to a close, a group of off-roaders pulled up in side-by-sides.

“What was beautiful is the medicine woman was talking to the kids who had climbed out of these RZRs about how this place needs to be looked after, and how the boulders are ancestors,” Newman says. “It was an incredible confluence of things, and that’s the special thing about Giant Rock. It brings a lot of different people together.”

Everybody loves Tripod the three-legged coyote, but High Desert locals say that visitors are spoiling the beast with handouts and causing a dangerous situation.