Kwang Uh and Mina Park’s reinvention of Baroo, one of L.A.’s defining restaurants last decade, builds on a legacy of creativity and Korean identity. Critic Bill Addison names it Restaurant of the Year.

The third of six courses at Baroo — the dish where the momentum behind Kwang Uh’s modern Korean cooking, light and assured, becomes fully realized — is a ssam of fried sole, built on a leaf of butter lettuce that lives up to its name.

Its soft pleats cradle the fish, sheathed in a batter made from three flours and vodka for maximum crunch, and latticed with powdered seaweed to give the appearance of tiny green veins. Red shiso and perilla bring their distinct, mint-adjacent sharpness. Sauces of gooseberry emulsion and seaweed remoulade go in separate directions, astringent and rich, creating tightly pulled contrasts.

Each element adds to an organic beauty that calls out to be clutched. Which is exactly the intention. In hand, the wrap disappears in four or five bites. In memory, the layered intrigues will keep hanging around.

The tasting menu at Baroo 2.0 is worlds apart from the madcap grain bowls Kwang Uh created at the original restaurant. But his maturing style still shows a wild streak.

The whole experience of dining in Baroo’s comfortably elegant Arts District dining room can be like this.

At face value, it’s a beautiful tasting menu, priced at $110 per person and paced at a pleasing clip to reassure Angelenos otherwise impatient with prix fixe dinners. The emphasis is on vegetables and herbs and seafood; one course comprises densely delicious short rib or pork collar meat alongside a singular bowl of rice seasoned with things like dried shepherd’s purse (a plant in the mustard family) and XO sauce fashioned from chorizo. Uh is a master with fermentation. Kimchi, pickles, the Korean building blocks of soybean-based jangs and even buttermilk, paired in one sauce with lemongrass, open doors to unseen worlds of flavor. In Los Angeles, where traditional expressions of the cuisine define the Korean restaurant ethos, Baroo stands apart as the city’s most persuasive foray into innovation.

He popularized shrimp tacos in Los Angeles and has been the bridge between classic food trucks and a new generation of street food vendors.

Baroo’s Tae, a course of dan hobak, ssanghwacha cappuccino, seed puff, and red yeast makgeolli with ndnja, gouda, and pinkberry. (Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

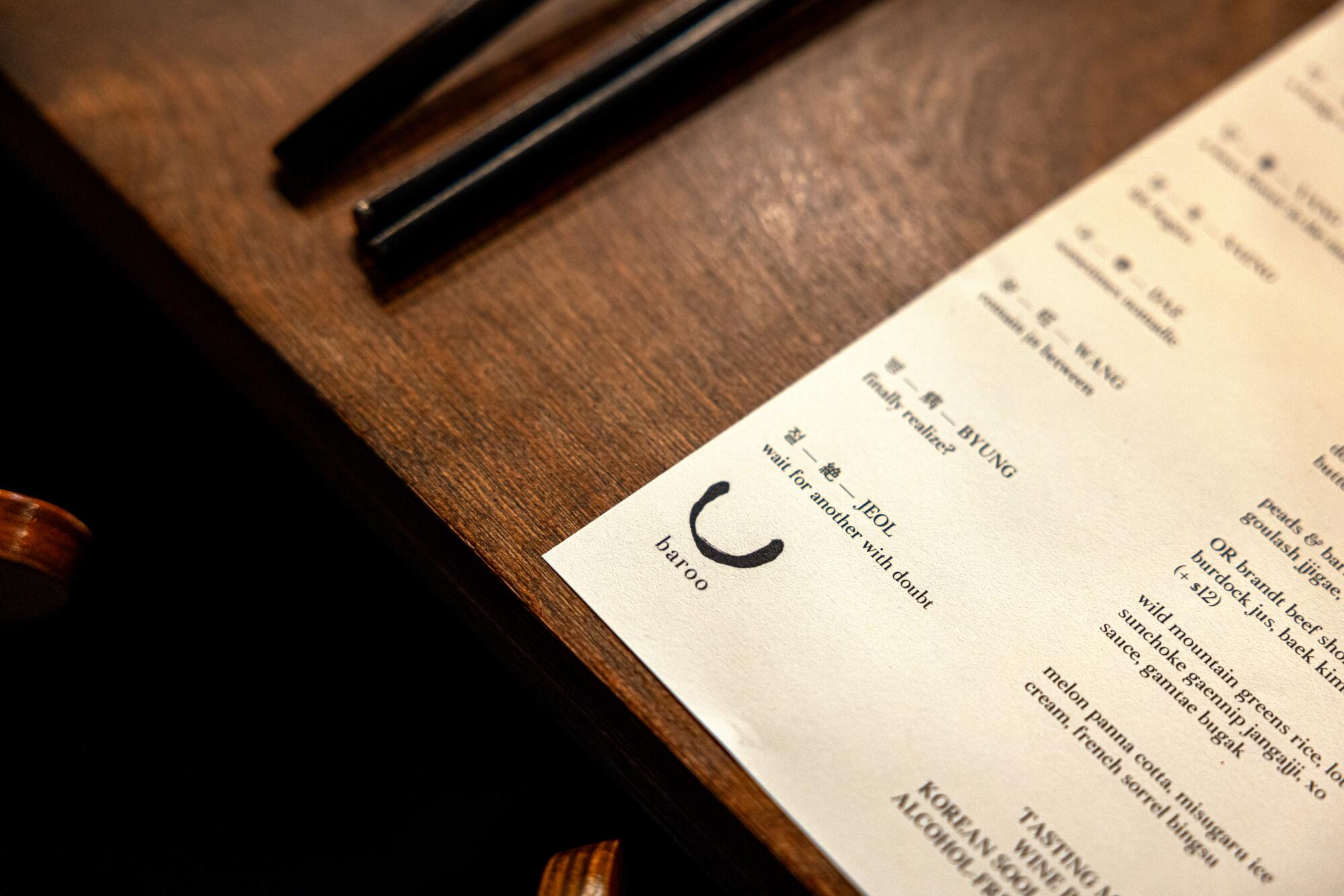

Diners enjoy the dinner service at Baroo. (Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

There’s also plenty more powerful context if you go looking for it.

Baroo, with its many longtime fans (I’m among them), began as a project nearly a decade ago in an unassuming Hollywood strip mall. Uh, partnering initially with his childhood friend Matthew Kim, poured years of culinary education and kitchen gigs around the globe into intricate, wildly satisfying grain bowls and pastas they sold for $9 to $15 each.

Having just the pair run the place was taxing to the point of unsustainability. In 2017, after the restaurant had received waves of local and national acclaim, Uh left the restaurant for more than six months to live at the Baekyangsa temple in South Korea. He was there to apprentice with Jeong Kwan, the Zen Buddhist nun and chef who received worldwide attention the same year for appearing in an episode of “Chef’s Table” on Netflix. While there, Uh also met chef and writer Mina Park. They eventually married and became business partners, charting the future for Baroo after its first iteration closed for good in the fall of 2018.

Even before its Arts District reincarnation finally came to light last September, Baroo lingered in L.A.’s restaurant consciousness. Yes, the model was untenable, but the insanely detailed grain bowls and noodles with gochujang-revved oxtail ragù were like nothing before or since: mind-jangling, comforting, stubbornly affordable. Above all, the cooking was personal and full of grace. Uh broke through to something fresh in those dishes by connecting to his identity — all of it, his origins, travels, curiosity, intellect and imagination.

Creating menus that tap into a chef’s narrative is endemic to L.A., from taco street carts to omakase counters. But the synthesis of ideas in Baroo’s cooking was empowering in a new way. Even if none of our next generation of talents ate at Uh’s original restaurant, I see a throughline of self-determination among recent achievers that began as pandemic-era pop-ups. Upstarts like Kuya Lord, Quarter Sheets, Villa’s Tacos, Poltergeist and Azizam. Taste the cooking at any of these places and you’ll know something about the people who conceived the dishes. Their successes come with a reminder: No life takes a straight line.

At the old Baroo, I would sneak glances of Uh standing at the stove alone in the small, cloistered room. I could never tell if he looked meditative or on the verge of a meltdown. Likely it was both? Now I see him in his open kitchen surrounded by staff. He looks intent but fundamentally happier. No naivety here: Running any restaurant is grueling. But Uh and Park have refashioned an ephemeral legend into a working actuality. That’s inspiring in its own right, and Uh continues to evolve in his craft.

With 24 hours’ advance notice, for example, you can order a vegetarian version of the tasting menu, immediately one of L.A.’s most brilliantly realized plant-based feasts. Headlining is bansang, a tray with bowls of the wondrously seasoned rice (minus chorizo) and banchan of seasonal vegetables along with evergreen treasures like dried acorn jelly with the thick chew of cavatelli. There’s a soup so profound and minerally, so unfathomable in its distillation of seaweeds and mushrooms and other flora, that spoonfuls of it take me back to the wildness of Uh’s revelations last decade. The meal began with “pine kombucha cappuccino,” a variation on Korean jatjuk that extracts the essence of pine nuts into a milky liquor. It was a calming start and, in its depths, a little mysterious. After all these years, in a triumphant return, one of our greatest culinary minds can still keep us guessing. As he should.

Baroo is the L.A. Times’ Restaurant of the Year for 2024.

Restaurant of the Year will be presented to Baroo’s Kwang Uh and Mina Park during this year’s Food Bowl festival at Paramount Studios on Sept. 20. Tickets are on sale this week at lafoodbowl.com.

Past Restaurant of the Year winners

Why we chose the newly expanded mariscos stand in Historic South-Central’s Mercado la Paloma as our Restaurant of the Year.

Critic Bill Addison explains why Justin Pichetrungsi’s Anajak Thai became one of the most eye-opening meals to have in Los Angeles.

Phenakite is an ambitious fine-dining project with the most heartfelt cooking in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles Times 2020 restaurant of the year award

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.