Staking claim to a new bohemia

A cold, insistent wind twirls about the high desert sands of Joshua Tree, pushing through doorways, penetrating layers of wool and leather and whipping errant strands of hair across the face.

Up a remote twist of uneven, cleft-ridden dirt roads made more precarious by recent rains, vehicles bump and wobble as if they’re mule-drawn wagons. Here and there, cottontails and kangaroo rats scuttle through the scrub brush of the uncompromising terrain.

FOR THE RECORD:

Joshua Tree businesses —An article in Thursday’s Home section referred to a B&B and gift shop owned by Mindy Kaufman and Drew Reese as Slim and Margie’s. The businesses are Spin and Margie’s Desert Hideaway and Spin and Margie’s Trading Post. Also, the Desert Hideaway is a motel, not a B&B.

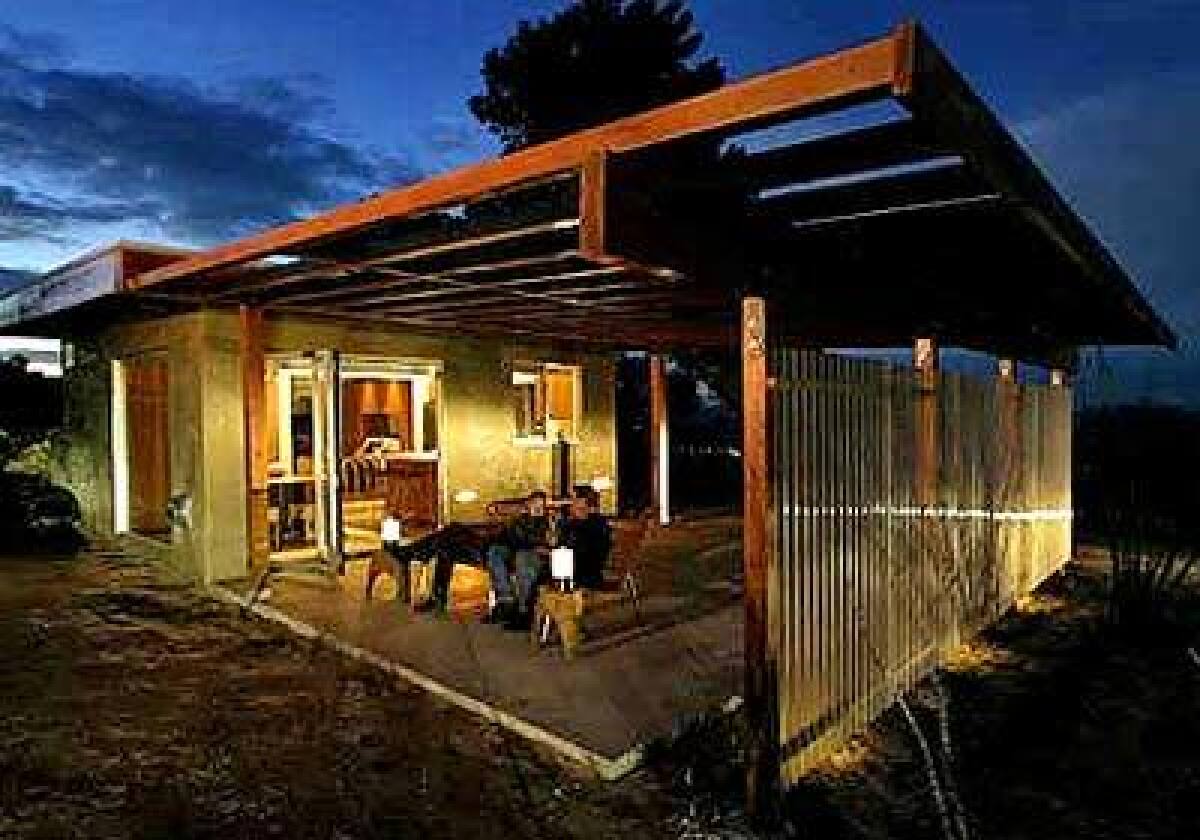

A water tower breaks into view, and just beyond it a rough-hewn, one-room cabin that is the second home of Ron Radziner, an L.A. architect known for designing boldly contemporary multimillion-dollar houses, and his wife, Robin Cottle, a graphics designer.

They couldn’t be more content out here in rattlesnake and black widow country in what they call, with but a slight exaggeration given that it has no electricity and only a pull-down screen to separate the bathroom, “our shack.” Look at the rocks, they point out, their colors, the trees among the boulders, the quality of the light, the 360-degree view, the wildlife: roadrunners, hawks, a gliding raven in the distance. And notice the silence. The utter, astonishing quiet. Could they ask for more?

Superlatives fall freely from the lips of the hardy pioneers in Joshua Tree who have been snapping up acreage with a fervor that has so intensified over the past five years, real estate values have shot up by close to 50%. Although it’s still relatively affordable in L.A. terms, “lower-end inventory, the typical little cabin on 5 acres for as low as $10,000 or $15,000, is now almost extinct,” says Barbara Weeda, a Realtor. “But if you can pay $250,000 or $300,000, you can still find good property” — often within walking distance of the Joshua Tree National Park entrance.

The existing architecture in Joshua Tree is by and large undistinguished, shack or not, and many houses are all but uninhabitable without tearing them down to the studs and starting over. But it’s more the lay of the land, the surrounding views and the general atmosphere that buyers clamor for.

Others besides Radziner and Cottle who bought in time talk too about the silence, although they might call it stillness instead, and they talk about the solitude and the clear expansive sky of day and the inky velvet sky of night splashed with stars that seem more intimate and brilliant in this smogless desert area where they say they can breathe and clear out the psychic cobwebs.

Sandwiched between Yucca Valley and Twentynine Palms in the Morongo Basin, the tiny unincorporated community of 10,000 is the anti-Palm Springs of the Mojave, attracting the chic-phobic looking for serenity, anonymity and the nitty-gritty of the wild.

“The mountains around Palm Springs are beautiful,” Radziner observes. “But when I’m there I don’t feel like I’ve really left L.A. Here I feel alive and back in touch with nature. I’m looking for isolation rather than a social environment.”

You’re not likely to encounter the Polo and pedicure set unless they’re lost or on their way somewhere else. Joshua Tree is the new mecca for the artistically inclined who want to escape the chaos and distractions of city life to produce their work. Musicians, painters, sculptors, designers and writers and the occasional recovering corporate refugee make up a good portion of the recent migration.

Eric Burdon has a house here and so do singer Victoria Williams and former Jayhawk Mark Olson, who live together, Johnette Napolitano of Concrete Blonde, the trio from Gram Rabbit, actress Ann Magnuson and her husband, architect John Bertram, furniture designer Blake Simpson, ceramist Juanita Jimenez, Steve Hall of Your Mother Underground Films and installation artist Andrea Zittel, to name a few of the more visible counterculturists. Painter Ed Ruscha is off somewhere in the rural environs, and rumors circulate that Joni Mitchell, Lucinda Williams and Bob Dylan are house-hunting. The late objet trouvé assemblage artist Noah Purifoy lived there in a double-wide trailer and left behind a wondrous 2 1/2 -acre sculpture garden of scores of works created out of everything including the kitchen sink.

Adam Peters — an English-born cellist and composer formerly of Echo and the Bunnymen and currently heard on the No. 1 album in England playing for a group called Athletes — moved here from New York on the spur of the moment last month with his singer-artist wife Korinna Knoll, with whom he has formed a “left-field European pop music” duo, Neulander.

The couple had never been to Joshua Tree before taking a house on the basis of a realty photo, but “we just felt a kind of calling to come here,” he says. “We wanted to live out in the middle of nowhere close to somewhere. We’d seen enough galleries and been to enough gigs and I didn’t want to see or hear anything else. All I wanted to do was work.”

He was unaware of how many other musicians have migrated here, although he knew that country-rocker Gram Parsons had died of an overdose of morphine and tequila in a Joshua Tree motel in the ‘70s and he’s been once to Pappy and Harriet’s, a cantina built as part of a western stage set in the 1940s in nearby Pioneertown and owned for a year and a half by two ex-New Yorkers, Linda Crantz and Robyn Celia. It’s an institutional nighttime hangout, where Lucinda Williams, Shelby Lynne and Michelle Shocked have played, with music ranging from country to rockabilly to swing.

Musicians have also recorded at the high-tech local studio Rancho de la Luna and at Integraton, a parabolic sound chamber in the nearby town of Landers. More than one album has been inspired by the area, including U2’s “The Joshua Tree” and Concrete Blonde’s “Mojave, “ and this May, the third annual three-day Joshua Tree Music Festival will be held here.

“Joshua Tree has a strong, wild identity, but it’s not what I’d call hip or trendy,” says Peters. Certainly not hip or trendy in the common understanding of the terms, true, and the squirming and the sneering among locals that would accompany such a suggestion is all too clearly imaginable.

“It’ll never become Hollywoodized, at least not for long,” says Peters. “There’s nothing to do, and it’s too tough an environment for most people.” And when the going gets tough, the tough don’t go shopping here. For one thing, there would be almost no place to do it. What passes for a town — more a village, really — is simply a three- or four-block strip of commercial buildings on Highway 62, a blip on the San Bernardino County map. There are radically few amenities in Joshua Tree.

Peters aside, what initially draws this motley cadre of desert nonconformists is, almost universally, the landscape, a Tolkien-esque dreamscape hypnotic in its power. Boulder piles can rise as tall as a six-story building and give off hallucinatory resemblances to faces, skulls and other body parts.

The Joshua tree itself, although described by early settlers as “grotesque,” “tormented,” “repulsive” for its crazy configurations of crooked branching, has a poignant beauty that can touch you in a way that makes it seem bizarrely human. (The anthropomorphizing of geology and vegetation is not uncommon out here.)

Mormons must have responded exactly that way when they named the tree, believing it looked like the prophet Joshua pointing them onward and upward to the promised land. There is an air of courage and stoic aloneness about the tree, this vulnerable maverick that grows only in the Mojave and only an inch or two a year on average, if it’s lucky enough to survive.

Joshua Tree National Park, 800,000 acres straddling the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, is, of course, the heart and soul of the region, and it’s the reason so many people come in the first place. They climb the world-famous rocks, hike, camp out, ride horses and bicycles on the trails.

“It’s one big piece of art,” says Magnuson, “so spiritual and prehistoric and timeless. The instant you enter, everything outside melts away, as if the whole world is covered with Joshua trees and those Yves Tanguy rocks.”

The park is what brought Mindy Kaufman and her husband, Drew Reese, from San Francisco, and James Berg and Frederick Fulmer from Los Angeles. Kaufman, a former home accessories designer who created products for such clients as Restoration Hardware and Pottery Barn, and Reese, who was a wine consultant, bought a house in 1997 because they loved the rocks and the wide open spaces.

“Everything felt like an opportunity and an adventure,” says Kaufman. “You could buy a house in the valley for a car payment back then. It was insane.” Their friends thought they were insane as well. The couple wondered about that themselves. “I was resigned to the fact that all my friends would be in San Francisco. Then I discovered there’s a weird convergence of people here, a fantastic community I’ve grown to love. It’s unique and quirky. But I never thought of Joshua Tree as becoming this kind of mecca.”

A mecca, says graphics designer Clea Benson, “poised to become a haven for like-minded souls who love the arts and the park and who are environmentally conscious.” She spends every weekend with her husband, John Schuster, a lawyer, in a cabin that was remodeled by Radziner. “It’s a tight-knit community full of very devoted, fiercely loyal people dedicated to Joshua Tree. We now have more friends here than we have in L.A.”

Reese says there’s a Joshua Tree style as opposed to the desert style of places like Santa Fe or Scottsdale. “The thing that sets it apart is people buy shacks or cabins and gut the entire thing, blow out walls, put in doors and overhangs, do whatever they want. They’re incredibly inventive in how they decorate.”

In other words, there are no rules here, no historical societies restricting what you can and can’t do, no right or wrong, no status competitions. People furnish from thrift stores, they furnish with almost nothing, they go Mexican, they go Moroccan, and they generally do it themselves. “It’s a style that has elements from all over the world,” says Reese.

He and Kaufman ripped out the shag carpeting in their ‘70s-era midcentury house, the fake paneling, the wallpaper, the metal fireplace. After a phase of being conservative with color, they painted over the tame sages and beiges with red, orange, gold, teal. “We thought, ‘Yeah!’ There’s a freer expression here, a sense that you can do whatever you want,” says Reese. “The desert opens up the floodgates of your imagination.”

Berg, a TV script writer, and Fulmer, a painter, started coming on weekends to camp. “It’s the magical draw of the desert,” says Fulmer. “It speaks to you.”

One day they happened upon an abandoned halfway house where the residents had washed and groomed dogs. The view on all sides was stunning. They wanted it, they made a call, they bought it just like that, over the phone, all 3,400 trashed square feet with its 30 bunk beds. A bottom-to-top renovation and furnishings collected at local yard sales transformed it into a cleverly appointed, comfortable home. Fulmer has kept all the springs of the bunk beds to create an outdoor art piece.

“We’d gotten to the point in our lives where peace and quiet was getting important to us,” says Berg. “An occasional weekend fix was not enough. We became addicted to the reinvigoration. We see the sky and the puffy clouds and smell the creosote bushes and the stress just fades away. So it’s still kind of a halfway house except the drug is stress. And the dog hairs are still all over the house.”

Besides the nine campgrounds, the 200 miles of equestrian trails and the nearly two dozen hiking trails, the park’s remarkable boulder formations have made it one of the top rock-climbing destinations in the world. On any given day, a stream of climbers — who constitute their own subculture in Joshua Tree — come in and out of Coyote Corner, a general store of sorts selling climbers’ salve, bottled water, hammocks, guidebooks, a hodgepodge of notions and souvenirs.

The owner, Ethan Feltges, referred to by one local as “the unofficial mayor of Joshua Tree,” lets them wash off in back of the shop, where he has installed outdoor showers as a token of the hospitableness so often evident in this convivial, neighborly place.

Feltges was born and raised in Joshua Tree, and he knows just about everybody in town or at least knows of them, along with a little something about them, and if he doesn’t, you’re reasonably certain he soon will. He’s seen the rapid changes in his hometown just since the beginning of the new millennium, and the possibility that Joshua Tree could fall prey to the kind of territorial marring by chain stores and fast-food franchises that has turned Yucca Valley and Twentynine Palms into Anywhere, USA, disturbs him.

“We’re the rose between the thorns,” says Feltges. “But I’m scared. Yucca Valley is exactly what a town should not do. Technically, all Joshua Tree is just a bunch of buildings. There’s no political entity. We have no government and therefore no control over what happens.

“Property sales have already skyrocketed. More houses have gone up in the last year than in the last 10. Prices are 10 times higher in some areas. Five years ago you could find things so cheap, you could put them on your credit card.”

Still, they come, and many of the part-timers eventually make it full time. A few of them are even buying commercial properties.

Jimenez, who has taught art at Pasadena’s Westridge School for 34 years, plans to retire in four years to the house she gutted and rebuilt and create her ceramics in the hangar-like studio she created from scratch. Kaufman and Reese moved there permanently in 2000 and now own Slim & Margie’s Bed and Breakfast and Slim & Margie’s Gift Shop. Blake Simpson left Silver Lake for good and operates his furniture design business in a studio next to his house with business partner Isaac Correa. He is also putting the finishing touches on a run-down seven-room hotel he bought, the Oleander, for which he is creating all the furnishings. Benson and Schuster have bought two buildings in town, one of which houses Rattler, a New York-style deli, the Joshua Tree Outfitters sporting goods store, and Weeda’s realty firm.

“There’s such a strong sense of community here and the opportunity to make a difference,” says Benson. “That’s why we started buying commercial properties. Just by fixing up that one building we really changed downtown. It added so much to the vibrancy. You can’t fix up a building in Los Angeles and have it change much of anything.

“Joshua Tree draws people looking for a retreat from big-city life. We love the small-town atmosphere here. This is definitely where we intend to end up one day. Full time.”

Barbara King can be reached at barbara.king@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.