Patrice Pinaquy: (very) old-school craftsman

Patrice Pinaquy doesn’t just make furniture that looks like it came from the 17th century. He builds furniture as though this were the 17th century. Using techniques that are as antique as his tools, the craftsman can spend more than 1,000 hours on a single table. He says his collection of antique woodworking tools may be one of the largest in the world. Its certainly one of the few actually in use. If a tool breaks, theres a good chance he will simply make a new one, just like his predecessors did in 1700. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

Patrice Pinaquy doesn’t just make furniture that looks like it came from the 17th century. He builds furniture as though this were the 17th century.

Pinaquy, 61, is a native of Biarritz in southwestern France, and he trained in France for two years, taught by the elders of hand-powered woodworking. He came to the U.S. in his early 20s, eventually landing an office job in Los Angeles. As he explored the city, he wondered: Where was the evidence of the kind of artistic craftsmanship that surrounded him in Europe? It came from a strong sense of nostalgia, he says. Here, things are made for everybody and thats good, but there are a few people that want the special object, a special treasure. It could be a piece of jewelry or a castle or anything in between. I didnt want to make something that came out of Levitz, so after a few years I went back to France to get formal training. Here, a tool-lined wall in his studio. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

One of Pinaquys early projects was this tea table (done in Louis XV style) in the front hallway of his home. Using the processes of eras past is not some Renaissance fair stunt but rather a logical approach to replicating, restoring or repairing 300-year-old furniture, he says. Pinaquy is one of a few experts called by the Huntington Library, Hearst Castle or the Getty when an antique needs restoration. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

A detail of the tea table: Gold-plated mountings accent the unstained Brazilian tulipwood and kingwood. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

Advertisement

Pinaquy and his wife, landscape architect Karen Adnoff, step into their living room, anchored by the Erard salon grand piano. When the couple first had it tuned, they discovered it had never been played. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

Examples of craftsmanship can be found throughout the house. In this 200-year-old armoire in the living room, square pegs were used instead of glues, allowing the piece to be disassembled easily for repair or tightening. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

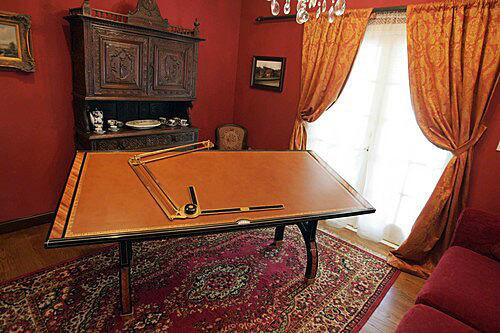

The drafting table that Pinaquy built for his wife is 7 feet wide and 3 feet deep, functional yet delicate, with ebony and tulipwood in the frame and inlays of silver and boxwood in the marquetry. The top is leather embossed with a scroll of gold leaf, done by a specialist in France who had just worked on the desks of the French Senate. The brass arms, cut from a single piece, are plated in gold and engraved. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

The dining room table is a replica of one that Pinaquy made for Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones. It can seat 22 people when the leaves are in. Pinaquy brings up the gloss with the time-consuming French polish method, applying scores of thin layers of shellac and alcohol. Customers pay more for French polishing, he says, but if you get any scratches, you can still touch it up 300 years later. This is where the machine stops and the hand work fills in the gap of excellence.” (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

Advertisement

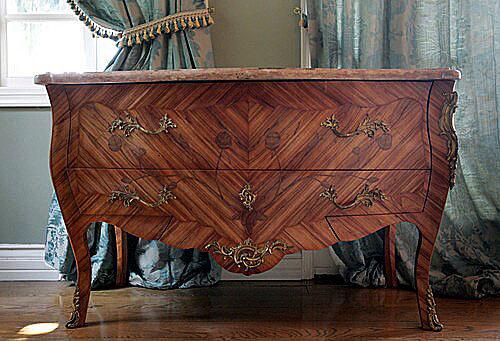

This Bombay commode was one of Pinaquy’s first pieces. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

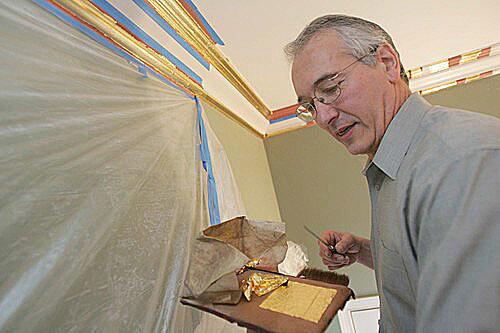

Pinaquy applies gold leaf to molding in his bedroom using a bed of lamb leather partially enclosed with goatskin parchment. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

The portrait of handmade craftsmanship: another example of Pinaquy’s artistry. He and Adnoff say they plan to build a French chateau entirely by hand, using materials and tools ropes, hoists, scaffolding, planes, saws and chisels also made by hand. Going back to basics makes sense in a recession, but is building a monument to royal aesthetics sending the right message? You have to change the concept that art is a luxury, Pinaquy says. People need to dream. Thats why they go to the movies to escape the hard reality. This is part of the dream.

For a peek inside more Southern California homes and gardens, go to our Homes of The Times gallery. (Stefano Paltera / For The Times)