The 105 Freeway roared overhead as homeless outreach worker Daniel Ornelas knelt to speak with Genia Hope.

Hope’s home has been, for years, a sprawling complex of tents beside a tangle of freeways in southeast Los Angeles County. Like many homeless people, she has chosen to live under or near a freeway because it affords some measure of safety compared with other spots where homeless people bed down.

A rusted elephant trinket stood guard outside her tarps and tent, and inside she lounged on a black leather couch, smoking a cigarette alongside a rack of clothing.

Hope raised her now-grown children in Apple Valley and later followed a man to Bellflower. She lost her job at a rehab facility and then, after her partner died, grief, anxiety and struggles with addiction led her to the street.

Now, it looked as if Ornelas might just be able to help her. The COVID-19 pandemic has opened up a wealth of resources to help get people off the streets, and a recent order from a federal judge will unlock even more. But efforts to aid people like Hope are going to be complicated by a shortage of available shelter and fighting among government entities about how best to carry out the judge’s wishes.

Hope told Ornelas that living beside this freeway underpass, just off a bike bath that snakes along the Los Angeles River, was optimal. Police rarely hassled her here, and she had plenty of space to be alone. An on-again, off-again love interest lived nearby, and her homeless neighbors formed a supportive community.

One neighbor brought her some lunch and a strawberry slushie as she spoke with the outreach worker.

Ornelas asked if she would consider going to a shelter or to a trailer. Those were nonstarters. The first was too dangerous, the second too cramped, she said. How about a temporary setup in a hotel, he asked.

She jumped at the offer, excited at the prospect of getting to take a bath and sleep in a bed. Her matted blond hair needed washing, she said. It would be ideal if her boyfriend could join her — at arm’s length.

“If we could be at the same hotel and in separate rooms, that would be great,” she said. “Sometimes we just need a break from each other.”

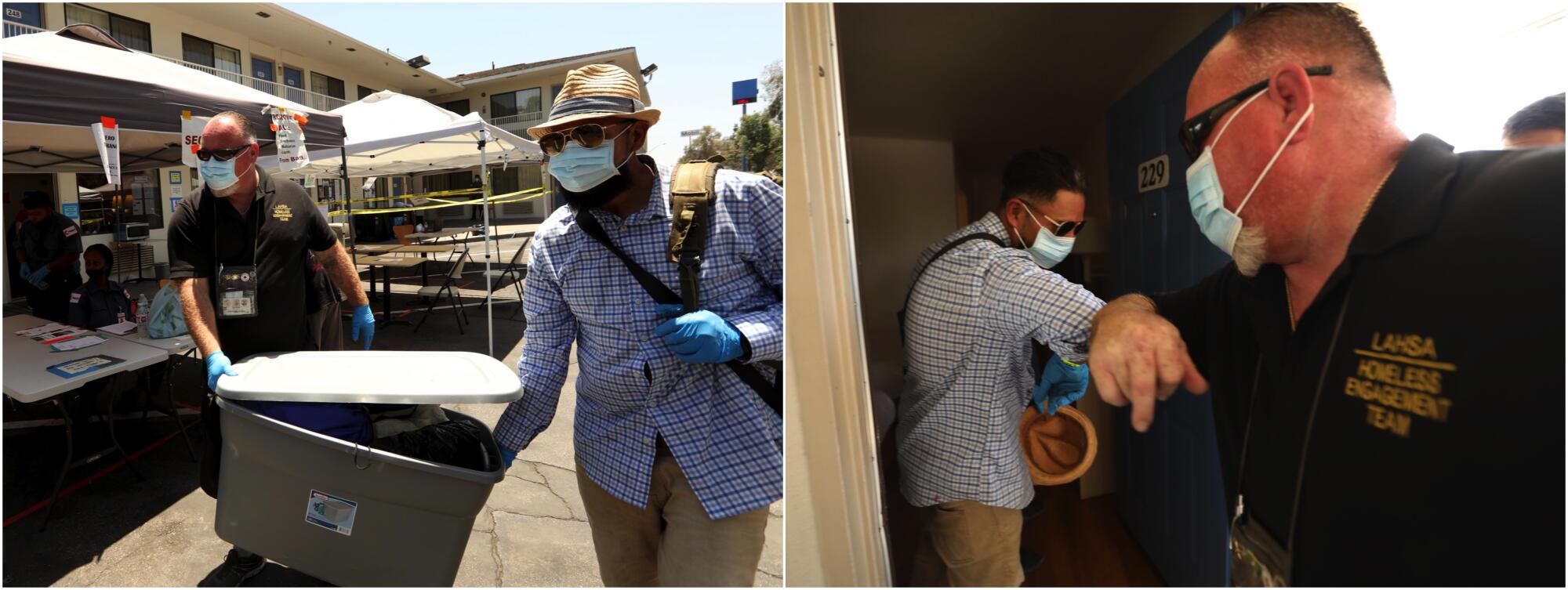

A government program known as Project Roomkey, which aims to rent motel and hotel rooms for homeless people, has fallen short of its goals locally but still has vastly expanded the number of rooms available to homeless people vulnerable to COVID-19. As a result, Ornelas was able to quickly whisk Hope off the street. Like many outreach workers who serve the county’s swelling homeless population, he pays special attention to the underpasses and embankments near freeways.

Those areas became a subject of great interest and conflict after U.S. District Judge David O. Carter ordered city and county officials to provide space in shelters or alternative housing for residents living near freeway overpasses, underpasses and ramps. Once there is enough shelter, the agreement could pave the way for law enforcement to enforce anti-camping ordinances.

The order came during proceedings for a lawsuit Carter has been presiding over since March, when the advocacy group L.A. Alliance for Human Rights sued public agencies across the county, accusing them of allowing unsafe and inhumane conditions in homeless camps. Carter’s focus on the areas around freeways took many homeless advocates and government officials by surprise.

An ambitious Los Angeles County plan to lease hotel and motel rooms for 15,000 medically vulnerable homeless people is falling far short of its goal and may never provide rooms for more than a third of the intended population.

Many who could be forced to move said they were leery of going into temporary shelters, tiny prefab houses or sanctioned camping sites, because they felt confined by rules that prevented them from leaving after certain hours and put them in shared spaces that they would otherwise avoid.

And those coordinating where people living near freeways go next — the homeless service providers and outreach workers— say that the order will lead to needless confrontation between law enforcement and people living on the streets. They also say politicians’ attempts to comply with the judge’s desires focus far too much on interim housing options and will come at the expense of more permanent solutions.

In addition, homeless service providers and officials from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority are feeling their resources and time stretched to the limit as they try to care for a population rife with preexisting conditions that put them at elevated risk of dying from the novel coronavirus. They say that fulfilling the order will distract from keeping the most vulnerable alive.

“You know, even if this wasn’t within the time of COVID, I’d be frustrated,” said Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority Executive Director Heidi Marston.

“But I think that a lot of my frustration comes from the fact that we’re in the middle of a global pandemic, and it just doesn’t feel consistent with what we need to be looking at right now as a response.”

LAHSA recently announced an $800-million plan to house Los Angeles County’s homeless people who are most vulnerable to the disease. Marston said an approach that focused too narrowly on where people lived as opposed to what their health condition was could attract more people to theunderpasses as they heard that more resources would be provided to people living under freeways.

There are an estimated 6,000 to 7,000 homeless people living near freeways in Los Angeles County. Marston and other homeless care providers have felt cut out of a process that will be influential in determining who gets help and who doesn’t.

“We’re the lead of the homeless system and we’re the lead for a reason, because you need experts to be doing the work,” Marston said. “Our expertise and our experience should be pulled on and relied on to help get us to the best place possible.”

The county will pay the city $53 million this year and $60 million a year for the following four years to help fund services for the 6,000 new beds that the city has agreed to create over the next 18 months.

The beds can also be used for people who are over 65 and who are medically vulnerable, but Carter, who declined to comment for this story, has focused his efforts on getting city council members to identify large encampments under freeways in their districts and offer solutions for how they might move those individuals. He has encouraged them to seek out interim housing that could immediately ease the crisis on the street.

“We’re the lead of the homeless system and we’re the lead for a reason, because you need experts to be doing the work.”

— Heidi Marston, Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority Executive Director

Earlier this month, each member of the Los Angeles City Council did just that, submitting plans for how they will help move people living near freeways in their districts. The plans include “interim housing,” according to court documents, meaning an expansion of the temporary shelters set up by the city in recent years. They would also include the construction of single-room prefabricated homes, as well as many more sanctioned parking lots where people can stay in their cars, and permitted sites where those with tents can bed down for the night.

The plans would also include the continued use of motels, hotels and state trailers along with rental assistance subsidies.

“This is why the judge and I said, you know what? We’re going to get along,” said L.A. Councilman Joe Buscaino.

“We need to create these tools to bring and restore order in our streets and move people through a system that has multiple options for that.”

Court documents show that each district plan so far is focused predominantly on interim housing options, including safe parking sites and modular homes. The plans are far from fleshed out, but the city estimates that it will cost about $50 million to build the interim housing that’s proposed. Another $25 million would be spent to operate the facilities.

And $5 million would be spent on setting up and running lots for homeless people to stay in cars.

In recent weeks, the City Council has proposed and Mayor Eric Garcetti has approved setting aside $100 million that the city received in coronavirus relief funding from the federal government to execute these plans. By the end of the year, the city expects to have 700 new interim housing beds, 500 more hotel/motel rooms leased and 575 new safe parking spots, according to court documents.

At 76, Judge David Carter knows he shouldn’t be on skid row exposing himself to the coronavirus. But he wants more for L.A.’s homeless people.

City officials don’t yet have an estimate for how much more they would spend on responses such as rapid rehousing, which offers short-term rental assistance and services to those in need, but they hope to give Carter a more detailed set of plans by early August.

In recent weeks, the heads of the five most influential homeless services organizations wrote a letter to the City Council, decrying the strategy put forward by the court and city. The focus on interim housing and the freeways would not lift people out of homelessness, they said.

“The city’s aggressive plan is not philosophically aligned with L.A.’s current homeless services delivery system, and the plan is in no way guaranteed to be faster or more effective than the alternative plan we are proposing here,” the signatories wrote.

In the letter, which was obtained by The Times, they detailed how they had quickly surveyed their agencies and found nearly 3,500 housing units that could either be rented or acquired. Channeling funds toward filling those units with vulnerable Angelenos would be far better, they said.

“Large agencies like ours should be at the table from the start, weighing in. It’s frustrating,” said Va Lecia Adams Kellum, who signed the letter and is the president and chief executive of St. Joseph’s Center, which coordinates many of the homeless services on Los Angeles County’s Westside.

She was heartened to see that the City Council did intend to focus some efforts on rapid rehousing and using motels. But Adams Kellum and others said that although having interim housing such as temporary shelters was necessary, moving people without solving their homelessness just kicks the can down the road.

Last week, the heads of the five most influential homeless services organizations wrote a letter to the City Council, decrying the strategy put forward by the court and city. The focus on interim housing and the freeways would not lift people out of homelessness, they said.

In interviews with dozens of homeless people, outreach workers and government officials, The Times found that a specific set of reasons drew people to congregate under freeway underpasses.

Homeless people say they are safer from the elements, law enforcement and housed neighbors when they congregate near the freeway.

“You’re not in anyone’s yard, so the police won’t hassle you here,” said Jesse James Taylor, who is homeless and lives under the 10 freeway along Venice Boulevard in Mid-City.

Farther west, under the 10 near Pico Boulevard and Bundy Drive, George Grasso stood shirtless as outreach workers attempted to find out if he was interested in leaving his tent. Blaring traffic stilted the conversation and a red bandanna over his mouth made it even more difficult to understand what he had to say.

“The neighbors will call the cops on you. The cops will be there every day.”

— George Grasso, who lives under the 10 Freeway near Pico Boulevard

Grasso wanted to be able to smoke marijuana, which he’s prohibited from possessing inside the shelters and motels that are part of Project Roomkey. He wants a permanent housing solution but sought out this spot more than two years ago for several reasons. On a hot or rainy day, he said, the protection from the elements is a huge relief. Similarly, he added that if he were to set up his tent a few blocks in either direction on a street, homeowners would be all over him.

“The neighbors will call the cops on you. The cops will be there every day,” he said. “Here they give us very little trouble. I really don’t even go anywhere. There’s too much to look after.”

The shelters, he hears, are far less safe than his current situation.

In North Hollywood, passing traffic punctuated by beeping from oncoming cars offered a symphony of sorts as Michael Cooper, his back stooped, hurriedly moved detritus around, seemingly in search of something. A mop of blond hair hung over his eyes and Coke-bottle glasses sat on the tip of his nose.

The 59-year-old said he had graduated from USC and had been homeless for a long time. Recently, though, his prospects were looking up. After months of waiting, he had secured a room in a single room occupancy hotel downtown and he was moving in that week.

His spot under the 134 Freeway in North Hollywood had long been a refuge because there was little pedestrian foot traffic, and he was a “little more invisible here,” he said.

“That’s a lot of people they’re going to have to move. It’s going to be hard,” he said as he grabbed his backpack to head to the bus and his new home.

“I think it’s a reach to say it’s for the best interest of the homeless people.”

Watch LA Times Today at 7 PM on Spectrum News 1 on channel 1, on Cox systems in Palos Verdes and Orange County on channel 99, and live stream on the Spectrum News App.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.