How the pandemic led to a rare success in California’s effort to house the homeless

Natosha Johnson sat in a chair in the apartment building lobby, looking exhausted and rubbing her legs as her four children shuttled trash bags full of the family’s possessions into an elevator and then into their new two-bedroom apartment.

“It’s such a relief to be here,” said Johnson, 41, whose fatigue was a symptom of her lupus. “Our cramped situation was difficult, especially during COVID.”

Johnson and her children are among the beneficiaries of a state program, Project Homekey, that has quietly and efficiently purchased and rehabilitated buildings for homeless individuals. Before moving into this fourth-floor apartment in North Hills earlier this month, they had been sharing two beds in a cramped motel room.

They were among 40 families to get a spot in an apartment building purchased with a combination of funds from the state and the city of Los Angeles. The opening of the site in early December capped a five-month sprint to use federal coronavirus relief funds that had to be spent by the end of 2020.

Local government officials and nonprofit housing providers say they are excited by the speed and cheapness of the acquisitions compared to the usual siting and development of affordable housing or shelters. On average, the city spent about $230,000 per unit, which is far lower than what it takes to build a unit of permanent supportive housing — the type that is deemed most effective in breaking the cycle of homelessness.

The average cost of projects funded by a $1.2-billion bond program have risen from $350,000 to $531,000.

Project Homekey buys both motels and other types of buildings, and will eventually retrofit them for permanent housing. Converting motels is not a new idea, but the speed and flexibility the state offered local governments has resulted in one of the largest expansions in shelter for homeless people ever. Local officials credit a litany of factors, including the simplicity of the financing and the waiving of a series of regulations, including the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

The project followed another statewide effort, known as Project Roomkey, to move vulnerable homeless people into rented hotel rooms. As that has wound down, the Homekey purchases ramped up.

In total, a little over 95 projects totaling 6,000 units are planned to be purchased or have been purchased by municipalities or housing authorities, according to state officials. In Los Angeles, the city and county will add about 1,800 units — 1,000 in the city, the rest outside it. Some, such as the one where Johnson lives, will be immediately used as permanent supportive housing, in which social workers help people adjust to their new life. Others will start as interim housing, where people can move off the streets for a short time. Those will later be renovated and converted into permanent housing.

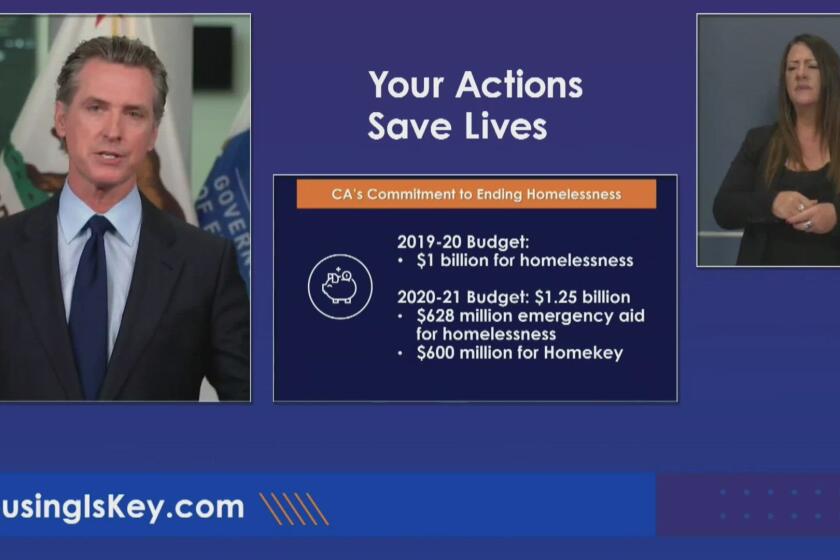

The state used about $750 million in federal coronavirus relief funds and augmented that with about $100 million in state money, along with philanthropic grants. It then expected municipalities to match some of this largesse with their own money.

“We started working on this at the end of July and we will have over 1,000 new units available within five months,” said Douglas Guthrie, president and CEO of the city Housing Authority.

“We can do the quick turnaround, and because of the nature of the buildings that we’re working with, and the price points we can acquire them for, it’s significantly less expensive than building something new from scratch.”

The purchases of these buildings, which are mostly motels, have not been without struggle. The county was forced to delay purchasing one motel in Commerce for permanent housing because formerly homeless tenants were still living there with nowhere to go.

This episode indicated another reality: that many people who had been living in the newly purchased motels were on the edge of homelessness themselves. In effect, the city and county would be swapping out one population of homeless people for another.

After a review, some motel guests were offered relocation assistance; others were offered space in shelters. None got to stay, and the former motel will now likely open in February after some renovations.

In some locales, attempts to purchase properties were stymied or delayed by local opposition.

Jason Elliot, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s senior advisor for homelessness, who spearheaded the program, credited the fact that the federal relief dollars had to be spent by the end of the year for the speed and success of Homekey. More important, he said, was state legislation that waived the need for CEQA and local land use approvals.

Of the nearly 1,000 units that the city purchased in recent months, about 210 will immediately become supportive housing for recipients of federal Section 8 housing vouchers. The rest will begin as interim housing and eventually undergo renovations so they can house people permanently.

Affordable housing, such as Section 8 and public housing, is available, but it often requires navigating applications and government agencies. Here’s what you need to know.

In practice that will mean adding kitchenettes.

“What I think was so extraordinary about this process was the ability to achieve pace and scale and open up units so quickly,” said LA Family Housing’s president and CEO Stephanie Klasky-Gamer.

Her organization provided the supportive services to people such as Johnson. It will also own and manage four other sites that will start off as interim housing and likely transition into permanent supportive housing in several years after renovations.

Klasky-Gamer and other local government officials said they hoped in the future more federal or state dollars could be allocated to buy more buildings.

The county purchased about 10 locations and 850 units and all but one of these locations will start as interim housing. This came at a cost of about $105 million.

Acquiring these hotels and turning some into interim housing immediately came with an added benefit: They already had people in them. That was a problem for permanent housing developments, but a plus for interim housing. In recognition of the urgency of the crisis, not only did the state require that the deals go through before the end of the year, they said that in most cases people had to be staying in these locations within 90 days of closing.

A usual affordable housing development involves multiple layers of financing progressing on differing timelines, adding complications and expenses to the construction of a building.

“This process illustrates the challenge that we have in affordable housing development — when you are navigating eight, nine different funding streams, it simply adds complexity and time to the process. It’s not like typical construction in the private market where you have, perhaps a single loan from the bank, and you’re basically off to construct immediately. With most affordable housing construction, you’ve got other timelines that you’re dependent on,” said Emilio Salas, the acting executive director for the Los Angeles County Development Authority

“So in this case, when you have a dedicated funding stream, which is mainly the federal government through the state, you can see just how quickly government can move to put housing online.”

The ownership of some of the Homekey buildings will be transferred to nonprofits while others will be managed by housing authorities. The North Hills building holds families who will only have to pay a portion of their rent.

It was a hive of activity as staff from LA Family Housing helped the newcomers navigate the the documents they needed to sign. New residents placed their possessions in trash bags for 20 minutes in the subterranean garage to ward off bed bugs and staff constructed cabinets and ripped the packing off new mattresses.

The mood among the residents was a mix of celebration, relief and being overwhelmed by how drastically their lives would change now that they had a permanent roof over their head. Some like Johnson only found out Monday that they were moving in Wednesday.

Advisor Jason Elliott reflects on the state’s response to homelessness during COVID-19 and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s mixed record on affordable housing.

The Georgia native had moved to California partially to be closer to her husband, who is currently incarcerated. Her four children had struggled to keep up their grades as they tried to study in a cramped motel room. Now Johnson will share a room with her youngest daughter, and her three other children will bunk together across the hall.

They’ll have some more space to do their work, and Johnson can feel some sense of relief knowing their situation is more stable.

“I won’t get excited until I can lay down and close the door to my bedroom,” Johnson said. “I’m just going to tell them to give me 10 minutes and close the door.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.