Southeast L.A. County cities enact rent control to keep residents housed

Stephanie Portillo has lived in her one-bedroom Maywood apartment with her son for 12 years, with rent increases she could afford until recently.

A new landlord purchased the complex in October 2021, when she was paying $1,000, and has since raised her rent to $1,245, she said. She received no notice about the most recent raise, nor was she aware it amounted to more than the 5% annually that state regulations allowed. In April, he asked her to sign a contract that would raise her rent to $1,675, a number well beyond what Portillo — and most of her neighbors — can afford.

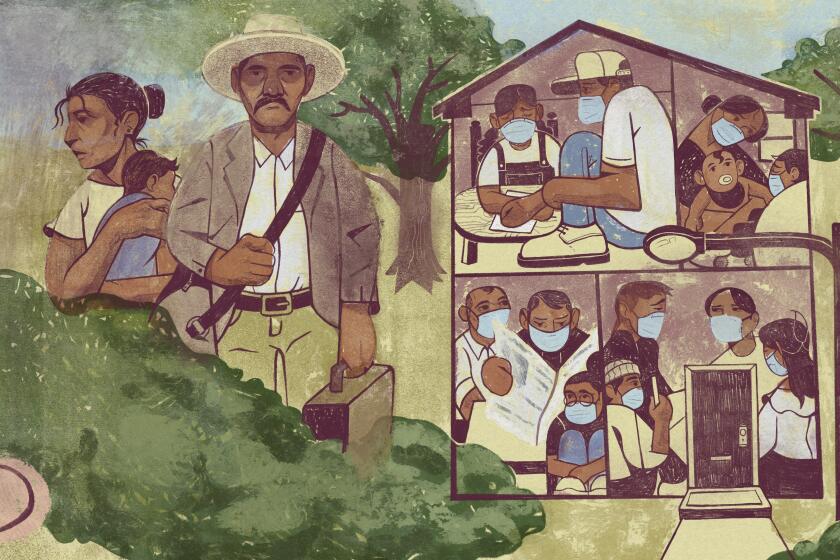

The hiked-up rents that have swept over so much of the region are now hitting once-affordable neighborhoods in Southeast Los Angeles County. The combination of higher prices, job losses and economic hits from the pandemic is sending some longtime residents to cheaper areas like the Inland Empire and high desert, or to different states altogether. And local officials are scrambling to keep people in their homes.

In February, Maywood issued a 60-day rent freeze, then extended it through September. On July 26, the City Council approved a rent stabilization ordinance to take effect when the rent freeze ends, limiting annual rent increases on all units to 4%.

Maywood’s efforts mirror those in the neighboring cities of Bell Gardens and Cudahy. These small, dense municipalities, three of the county’s so-called Gateway Cities, are populated largely by Latino and immigrant workers employed in the manufacturing, food and service industries, many of whom moved to the area decades ago in search of affordable housing near factories and warehouses.

With rents rising and renters making up over 73% of the population of Maywood, 86% of Cudahy and 79% of Bell Gardens, the cities’ leaders and activists realized they were facing a crisis.

It’s the cruel paradox at the center of Los Angeles housing.

“These are Latino immigrant communities, and they leave their homeland to come here to make community, and then all of a sudden they have to do it all over again,” said Martha Pineda, an activist with Las Vecinas Unidas who worked to pass rent control in Bell Gardens.

She says tackling housing affordability requires a web of solutions as price hikes span farther and farther outside Los Angeles and more affluent cities. Rent stabilization is the latest effort by Southeast cities to prevent the kind of gentrification that’s pushing longtime residents out of Eastside neighborhoods like Lincoln Heights and Highland Park.

In January 2020, California enacted a statewide law that limits most annual rent increases to 5% plus inflation.

Opponents of such moves argue that further rent control will amplify the problems that already hinder affordability by deterring new housing development and leading landlords to remove rental housing from the market.

“You’re disincentivizing new developments to go in, but in addition, you’re also causing existing unit supply to shrink,” said Jim Lapides, vice president of advocacy and strategic communications at the National Multifamily Housing Council, an apartment industry trade group. “It’s counterproductive; it actually ends up accelerating the very problem that [it] attempts to solve.”

The daily unknown

Like its neighbors, Maywood is a small city — just 1.18 square miles — with an estimated 24,000 people, many of them packed together into small homes and apartments.

The L.A. River and train tracks run along one edge of town, and industrial zones and dirt lots flank neighborhoods on two other sides. The city is transected by busy Slauson Avenue and Atlantic Boulevard, but it has its quiet neighborhoods, with little corner markets that go back to its farming days.

Jose Alvarez lives across from Carniceria el Pueblito, in an apartment upstairs from Stephanie Portillo‘s. He has considered Maywood home most of his life. The 32-year-old single father rents a one-bedroom apartment with his 12-year-old son. With the old landlord, he paid $775, then $840 per month.

But his new landlord, Joel Estrada, has drastically raised the rent. Estrada said in an email that Alvarez entered a rental agreement with him in September 2022 to pay $1,650 a month. He is allowing Alvarez until April 2024 to build up to the $1,650 rent. At this point Alvarez is paying $924.

Alvarez said he didn’t understand the lease he was signing because it was complicated and written in English, which he doesn’t know well. He can’t afford to pay $1,650 per month, but loves Maywood and cannot fathom leaving. Without his community, he said, “I would die.”

As the L.A. rental market soars out of reach for many working families, one community wants to hold on to its low-cost housing.

In April last year, he injured himself with a textile cleaning gun at work, and has a jagged scar on his arm to show for it. That July he applied for workers’ compensation, and a few months later he left the job. The checks arrived by the time he returned home in January from spending time with family in Mexico. Alvarez used the money to pay his rent for several months, then borrowed money from his friends.

Last month, he began a new job at a juice factory, where he makes the state minimum wage of $15.50 per hour. But the number of hours he’s scheduled to work varies each week.

“Don’t worry; I’ll help you,” his son told him, sensing his stress. But there is nothing his son can do. To keep up with rent, Alvarez had to borrow $800 from money he had set aside for his son.

“I feel like the proudest father in the world because of his innocence, and it showed me how much he loved me,” Alvarez said. “But at the same time, I also felt sad because I took money from him for something that I should be able to afford.”

In recent weeks, Alvarez has received notices that he is $280 behind on rent, but he says he has consistently made his $924 payment.

Downstairs, Portillo was offered $1,000 by the property manager to sign a contract, which she said would raise her rent to $1,675.

Estrada said he needs to renovate her unit, and promised her $4,494 in relocation assistance if she moved. Otherwise, he would raise her rent. Portillo did not take the $1,000 and refused to sign the contract on the advice of a lawyer.

Weeks later, in May, she received a 60-day notice to leave, even though Maywood has a ban on no-fault evictions. According to the notice, the landlord needed to renovate her unit.

The landlord rescinded the notice in July, and said it was an error.

This came weeks after she contacted him to say her electronic rent payment system wasn’t working, and days after The Times first reached out to him. Despite his attempts to get her to sign the new lease, Estrada said he had not raised Portillo’s rent over $1,193.

Other tenants in the building complain of notices with mixed messages about how much rent they have to pay.

“Landlords are all doing very different things,” said Alexander Ferrer, a UCLA graduate student who wrote a report about the corporatization of housing for the nonprofit Strategic Actions for a Just Economy. “One thing that rent stabilization does, which is super beneficial to tenants, is it helps you know what you can expect.”

Jasmine Gonzalez, who organizes tenants in Maywood with East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, agrees that consistent protections will minimize mistreatment from landlords.

“Regulations should hopefully change the mindset of landlords and management companies, because they’re aware that the city has taken initiative to support renters,” she said. “That should help with the wild behaviors we’re seeing.”

The opposition

Landlord associations point out that Los Angeles and cities across California already have rent stabilization ordinances. They say these laws drain financial resources from property owners and deter developers, which limits a vital fix to the housing crisis: the construction of new homes.

Proponents of rent control point out that under California’s Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, jurisdictions can enact rent control only on buildings constructed before 1995. But opponents say that because the law is under attack by politicians and activists, developers still hesitate to build in areas with rent control statutes on the books.

Opponents also say that small landlords can’t keep up with the rising costs of necessities like water, waste and insurance unless they raise rents. Rent control will push small landlords out of the market and corporate landlords will replace them, then renovate the units and lease them out at higher prices, says Daniel Yukelson of the Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles, an advocacy group for the rental industry.

Ferrer says that corporate landlords are more profit-driven, charge higher rates, and are quicker to evict.

Janet Gagnon of the Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles worries about the rhetoric from tenant organizations that drive the push toward rent control. She says anti-landlord sentiment at city council meetings, in community organizations and in the media drives divisions between landlords and tenants that make it harder for both parties to come to agreements about rent payments.

“We want to keep our mom and pops in business as responsible owners, as caring owners,” she said. “It’s also very shocking to us to see these outside forces coming in and trying to stir up animosity, hatred, and just bad feelings between the rental housing provider and the renter. Nobody wants to live in a war zone.”

The Southeast’s future

Dense areas like Maywood, Cudahy and Bell Gardens cannot rely on housing construction alone to keep homes affordable, said Maywood City Councilmember Eduardo De La Riva. Despite the opposition, members of the council are optimistic that rent control will keep their neighborhoods together.

“It’s a tool to preserve our community,” De La Riva said.

Elizabeth Alcantar, who championed rent stabilization in Cudahy, notes that many of the city’s residents fell behind on rent during the pandemic, and that not everyone received assistance.

“We saw increases that were beyond what we would recognize as legal and fair,” Alcantar said. “A [one-bedroom unit] in Cudahy will run you about $2,000. That’s $24,000 a year when our median income is around $40,000. So it’s just not feasible. That’s 50% percent of your income going just to rent.”

Now that rent control has taken effect in Cudahy, Alcantar said, the city has to educate renters and landlords about the new regulations in order to enforce them.

Last fall, Bell Gardens also implemented rent stabilization. But Pineda from Las Vecinas Unidas said the city has no clear enforcement mechanism for landlords who don’t comply with the ordinance or aren’t aware of it.

Bell Gardens City Councilmember Jorgel Chavez admits that implementing rent stabilization has been a “roller coaster at times.” Tenants still contact him with eviction threats, and corporate landlords outside the city can be hard to reach when this happens.

Still, Chavez said, rent stabilization is key for Southeast Los Angeles and its “minority brown folks just trying to get by.” He’s seen residents take on extra jobs because they can no longer afford to live on one paycheck per week.

Wilma Franco, head of Southeast L.A.’s SELA Collaborative, says that displacement driven by high home prices remains one of the group’s biggest concerns.

“If our community gets pushed out, what does that mean for the Southeast?” she asked. “What does it become?”

Times staff writer Ruben Vives contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.