Rick Dempsey found success in baseball, but his boyhood friend and teammate struggled

On a cool night in October 1988, Rick Dempsey, an aging catcher with his hometown Dodgers, stood as the crowd’s din went silent. Dempsey looked into blue and white that oscillated in the left-field bleachers at Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum and wondered whether Jim Loll might be there.

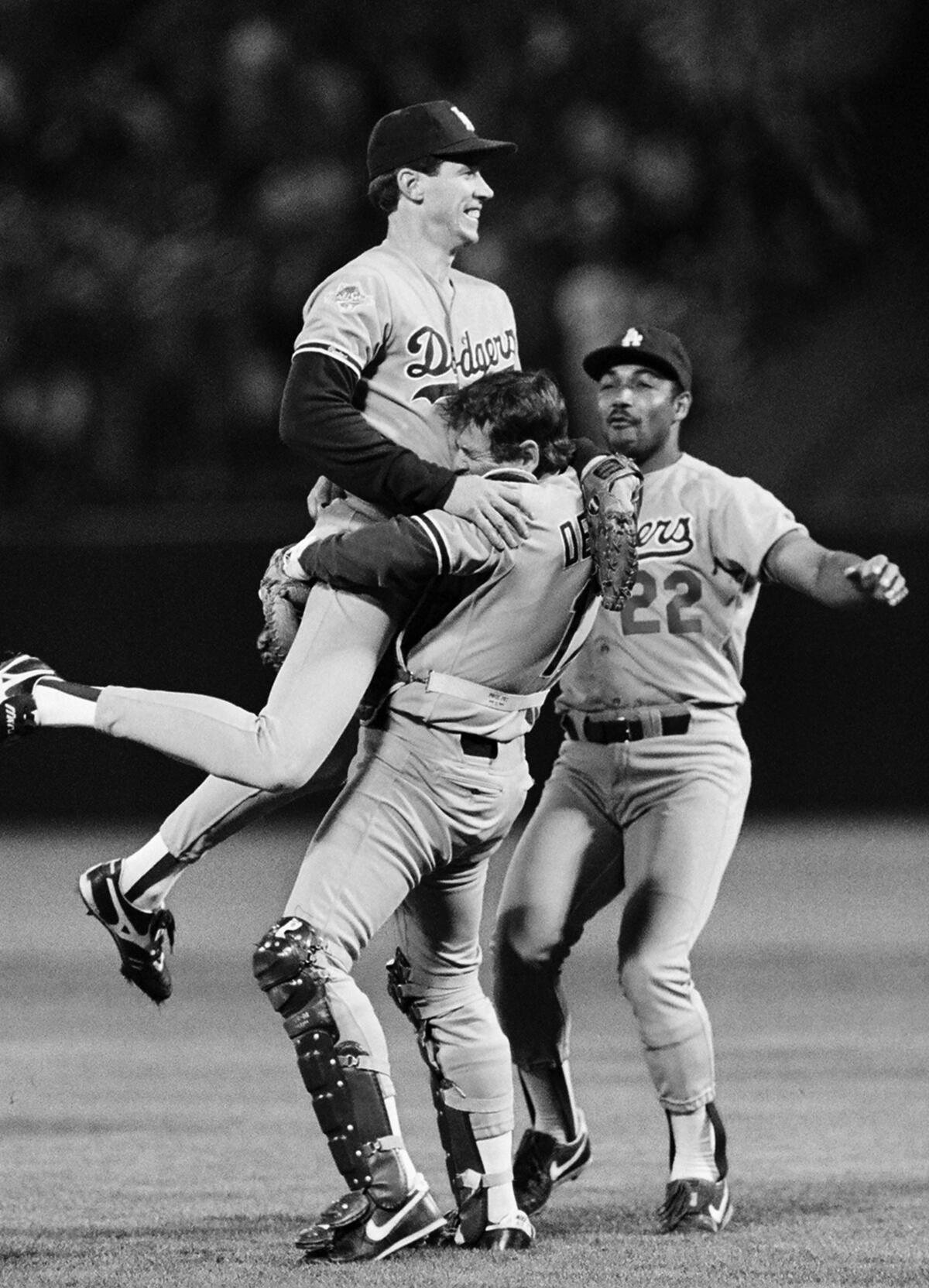

Dempsey crouched behind the plate and jutted down one index finger hard. Orel Hershiser’s stork-like delivery brought the fastball. Tony Phillips swung like a man who has been given a bad part in a play. And it was over. Like that. The Dodgers had beaten the Oakland Athletics in five games to win the World Series. “Like the 1969 Mets, it’s the impossible dream revisited,” declared an elated Vin Scully.

Dempsey leaped into Hershiser’s arms, and they were felled by a flood of Dodgers. But Loll, Dempsey’s best friend and teammate in high school, was not in the scrum, although it was Loll, not Dempsey, who had been drafted by the Dodgers when they were both 17.

In fact, Loll was one of the greatest high school athletes in Los Angeles history. Dempsey was the more modest prospect, though he would take into retirement two World Series rings. Any player would be happy with one. For some, like Loll, it would have been plenty just to be on the field.

This story is about the forgotten one, Jim Loll, the man Dempsey hoped to see in left field that night in 1988. About the friend you leave behind on the way to the top.

I was their classmate and, for a time, teammate. I knew them both — Rick and Jim — was awed by them both. I’d like to sing of the man who was unsung.

Similar backgrounds

Like Rick, who was born in Tennessee and in high school drove his buddies in an Appalachian-green truck spray-painted “Tennessee Rick and the Mountain Boys,” Jim came to California from the East because of a father’s restless hope for a better future.

Born Sept. 3, 1949, in Pittsburgh, Jim was the youngest of four children of a “very outspoken” engineer at Westinghouse, who led a strike against the giant electronics firm in the late ’40s. Bill Loll was, according to another son, Joe, “a strong personality, what you would call demanding.” Though not quite as rough as Rick’s father, Jim’s was “a tough disciplinarian.”

All such pressures — and natural grace — were taken to the baseball field.

“I’d hit two homers in a season, Jim would hit 10,” Joe said with the same wry Loll smile I recalled in his brother.

Jim and Rick met as 14-year-old freshmen at the new Catholic high school in Encino, Crespi Carmelite. Both born east of the Mississippi River, they now lived within a mile of each other in Woodland Hills and discovered they were darn good at sports.

By sophomore year, Jim already played on the varsity football and baseball teams. By junior year, he was backup quarterback on the 1966 team that went all the way to the California Interscholastic Federation AAA championship game, only to lose 7-0 because of a coverage breakdown on a near freezing, muddy night against West Covina.

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

Nicknamed “The Bear,” Jim was almost 6 feet 3 by senior year and 188 pounds. (He would grow to 210 in college.) There was something ursine about him; he had small ice-blue eyes sunk in ledges of bone, and yet he possessed a gentle, full-lipped mouth, though it was closed most of the time.

To many of his fellows, Jim seemed to observe the world from a high crag, a bit amused by his fellow Celts, maybe by life itself. According to his brother Joe, who went on to a successful accounting career, “Jim was a pretty smart kid. He was probably smarter than I was. But he was not excited about academics. He wouldn’t work as hard. It would come back to bite him.”

But not yet. In football, he played every minute of every game on three units: offense, defense and special teams as a kicker. In a city-wide all-star game, Jim stole the show as a quarterback and defensive lineman as West beat East 7-0.

As for baseball, Jim was fearsome, adding to his two Camino Real League batting titles a 0.98 earned-run average as a pitcher. Two photos in the 1967 Crespi yearbook capture his intensity. In one, Jim bites down on his lower lip as he cocks what looks like a curveball behind his planted, muscular left leg. “ ’The Bear’ uncoils,” the caption reads. Indeed.

The other shot is No. 36 at bat swinging. Jim’s arms are fully extended, showing his powerful forearm and bicep muscles, the bat tipped slightly up at 10 degrees. His left eye follows the tip of the bat on the ball to the outfield fences. This is a picture of hitting perfection, and I have never looked at it without thinking: Joe DiMaggio. That kind of grace, precision and power.

The pros saw promise in Jim and Rick, who batted .454 and .446 that senior year, respectively. The Dodgers drafted Jim in the 14th round; the Minnesota Twins took Rick in the 15th. Both were offered a paltry $6,000 signing bonus — about $46,000 in today’s dollars, but a ticket for even a chance at to the big-time.

The two celebrated. They checked maps to see how far Vero Beach (the Dodgers’ Florida spring training site) was from the Twins’ minor league training camp site in Melbourne.

Rick took the $6,000, kissed his wife-to-be goodbye (she was a close friend of Jim’s too) and went off to his first rookie ball team. For Jim, however, or more correctly, for his father, Bill Loll, the $6,000 was not enough. According to Joe, the father said he wanted more money for Jim’s college education.

Bill Loll got into a stare-down with the scout, Roger Craig, who had recruited his son. He too was a bear of a man at 6 feet 4 and a former Dodgers pitcher. Craig angrily took the offer off the table and left the Loll house. Still a minor, Jim stared at his father dumbfounded.

The Dodgers tried again a year later, taking Jim in the eighth round of the secondary phase of the January 1968 draft out of Los Angeles Pierce Junior College. But once again Jim did not sign, though a fellow from Rhode Island named Davey Lopes did. Jim now suffered a huge rupture whose significance neither he nor his father would realize until it was too late. With the exception of a brief time in 1985 when they tried to live together and Bill Loll cosigned for a $10,000 loan for Jim — which Bill had to repay — father and son hardly spoke for 30 years.

The lost chance with the Dodgers began Jim Loll’s long, tragic tumble, just as Rick Dempsey’s unlikely slow elevation began.

Taking different paths

Loll’s decline was not immediate. He racked up home runs playing at Pierce, including a legendary one said to have flown 500 feet, and was named Metropolitan Conference Player of the Year as a sophomore. But an invitation to play at USC by its great coach, Rod Dedeaux, never panned out. No one knows exactly why.

Stung again, Loll went to Valley State (now Cal State Northridge), where he took a pre-med course of study.

Desperate now in his sports goals, Loll hooked onto a semi-pro team affiliated with the Angels and caught the eye of a scout for the Kansas City Royals. Loll was exultant. He was sure this second chance would be the one for him to catch up to Dempsey.

But Loll’s performance with the Kansas City affiliate Kingsport Royals in Kingsport, Tenn., was untypically poor: In 33 games, he batted .109 (six for 55). That was the extent of his pro career. On his way back from Tennessee, Loll stopped to see Dempsey, who was playing with a Minnesota farm club in Charlotte, N.C. Dempsey tried to get Loll a tryout, circumventing the normal process. But it didn’t work and Loll returned to California, severely depressed.

“The window of opportunity is so short,” Dodgers historian Mark Langill said about players mustering out of the minors. “They’re like soldiers coming back from the war. There’s a loss of identity.”

Loll managed to pursue pre-med courses at Cal State Northridge, and it is probably there in the late ‘70s that he started taking drugs. He dropped out, somehow got a job with the Los Angeles Health Department, and in 1980 was divorced after five years of marriage. By then he was no longer consumed with baseball but instead a dark substitute — heroin.

For a while, Dempsey wasn’t sure he wasn’t headed to a similar fate. He was, after all, the child of an alcoholic. His six years with the Minnesota franchise were miserable. In 1972, he was traded to the New York Yankees to become another backup catcher, this time to one of the sport’s greats, Thurman Munson, who, to Dempsey’s chagrin, could “drink a fifth of Scotch and go out and hit two for four.”

After Dempsey dropped with one punch the third-string catcher who had baited him into a fight, the skinny catcher got more attention from the Yankees. In 1974, Dempsey threw out runners 73% of the time, 16 out of 22. Where was Jim Loll? As Dempsey put it, by the time he was traded to the Baltimore Orioles in 1976 and got his chance to shine as a starter, Loll “had just disappeared.”

Thriving in Baltimore

How is it I am here and he is there?

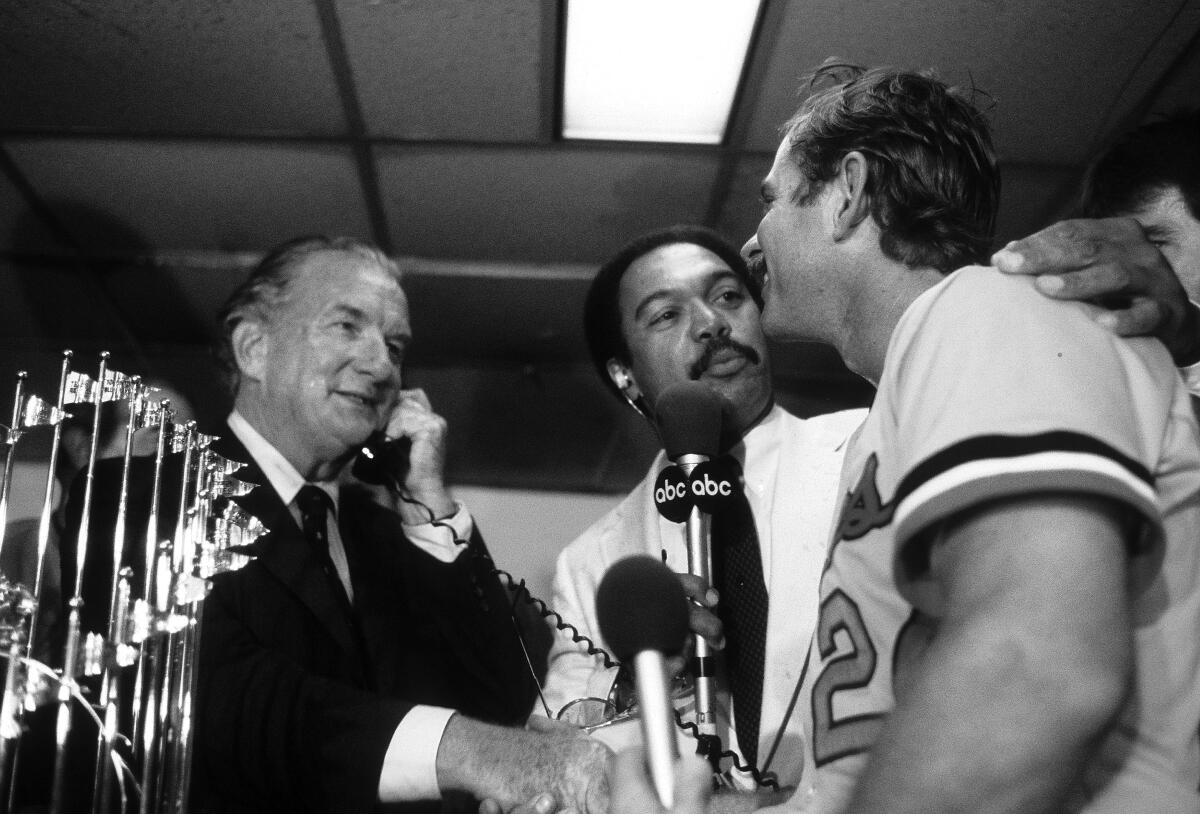

Dempsey would ask himself this question more than once in the 12 successful years with the Orioles, a team with whom he became a kind of legend. At peak moments — such as his unlikely most valuable player performance in the 1983 World Series when he batted .385 with four doubles and a homer — Dempsey would imagine Loll in the cascade of celebrating bodies coming at him.

“I wonder if we are all many people, not just ourselves,” Dempsey mused with me as we sat over lunch near his waterfront condo in Baltimore. “Maybe deja vu is true. Maybe we have lived others’ lives. Maybe they’re right there today. Occasionally, without knowing it, we cross paths with someone who is really us.”

I was struck by this. Dempsey wasn’t saying we crossed paths with someone who was partly us, or resembled us. But was us.

Baltimore was magic for Dempsey. Baltimoreans still recognize him on the street; today he does television pregame and postgame commentary for the Orioles, while his old battery-mate, Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer, is the color man. Many fans remember the rain dances. When rain delayed a game, Dempsey would walk out and face the discouraged crowd and dance, running the bases in the opposite direction.

So much in baseball, in all sports, is just there beyond the peg, above the vault, behind the throw in the dirt.

In a night game against the Angels in the 1980s when Dempsey threw out four runners to the delight of us high school friends, an old man walked from the shadows of the postgame parking lot with a couple of his cronies. It was Dempsey’s father.

“Where do you stay now, Dad?” he asked, forlorn.

In 1987, two miles from the son’s house, the father’s broken-down trailer was parked near a restaurant off Kanan Road in Agoura, where he was found dead.

“I miss my father today,” Dempsey told me. He has fond memories from his early boyhood, before alcohol took hold of his father and made him abusive. “I hated him, yes, for a long time, and protected my family from him. But I wish he could have seen (Rick’s sons) John and Christian grow up.”

In fact, we all lost our fathers too soon to one thing or another — Dempsey’s to drink, Loll’s to a fateful decision, mine to my disturbed sister, who then took her own life.

For all of Dempsey’s best years in baseball, he and Loll had no conversations. Dempsey tried to reach him at times but didn’t get through. Joe Loll opines that perhaps his brother was homeless for a time, but he isn’t sure as he couldn’t reach him either.

But, says Joe, by the late ’90s, when Dempsey was coaching with the Orioles, his brother Jim had had a turnaround. With the help of a private investigator, Joe learned that Jim was working at a van conversion company and living in Orange County with a new girlfriend he had met in Alcoholics Anonymous. Most encouraging, Jim had kicked the drugs and liquor.

In 1999, he even managed to reconcile with his father. After bucking up his courage, Joe picked up Jim at his apartment, drove him to their father’s place in Fullerton and knocked on the door, which opened. Father and son collapsed in each others’ arms, to great tears. (Bill Loll, in his 90s, still lives in Southern California and, according to his family, was unavailable to talk about his son.) At the time, Jim was even getting up the courage to reestablish his friendship with Dempsey.

But it wasn’t to be. On Nov. 21, 2001, Jim Loll died of an overdose. He was found by his girlfriend in their apartment.

In 2012, I was given the honor to induct Jim Loll posthumously into the Crespi Hall of Fame. Joe Loll attended the ceremony for his brother with his family. We sat together.

The big picture

When Dempsey and I met in Baltimore, I asked whether he had ever seen anyone in the Orioles’ minor league system as talented as “The Bear.” “Hundreds,” he said. “When they come in, they are so good and talented. And then they see: I’m in a place where talent is abundant — everyone has it. And many guys don’t know what to do, how to compete, because they’ve never had to.”

Perhaps that was one of Loll’s problems. He had such natural ability, he thought it would suffice. At baseball, Dempsey said, “he wasn’t a big-time worker.”

About our own unmet dreams — mine to get a secure university position, his to manage in the majors — Dempsey mused: “Ultimately, we all get taken down a peg, maybe many. We’re stripped naked, really. It’s at those times you’re held up by those who truly know you and love you. By the same token, we’re all given a choice — to crawl up and die, to be like the guy who goes to the market, gets his dinner, goes back to his apartment and crawls in bed. A hermit. But is that living? Avoiding conflict?“

“You have the choice, to live or not. And if you choose to live, you may as well go all out.”

Suddenly, I put my fork and knife down. He did the same. We looked at each other. What about those who didn’t have the buoyancy, or luck, who couldn’t take any solace from the love around them, if it was around them at all?

“Where do you think Jim is? Where is my sister?” I asked, almost dumbly.

“Your sister?” Dempsey repeated, inhaling, remembering her tragic end.

“None of us have an idea what is in the mind of God,” he said. There’s absolutely no way we can get a true focus on the reason for all that happens in our lives or others’. We just don’t have the scope. But, of course, all of us judge and get judged — but how much, really, can we, compared to God?

“The vision of God is so much larger than the huge set of rules we were brought up with. Think of it. We are all so human and weak. No one, I don’t care how strong he is, is perfect or able to get by without failing many times. And you do things oftentimes knowing they’re wrong, even saying to yourself you can’t help yourself. And the truth is — you can’t.”

Failure can be addictive too, but addiction is not necessarily failure. Or a final judgment.

“So how can I say where your sister is?” Dempsey looked at me, his hands opening, his fiery blue eyes dying down. “How can we judge her? Or Jim? Only God knows what was in their heart of hearts.”

“God gave your sister qualities maybe only He Himself saw; perhaps they were redemptive. We don’t know.”

Dempsey later said: “In the final analysis, maybe your sister’s life — and her death —were important in all kinds of ways you may not even see now. (She died 34 years ago.) Maybe the purpose of what she did was to affect you. To change you. To make you realize things for others she couldn’t herself.”

Dempsey took me to his balcony, and we looked out over the water. It seemed we had always shared waters — the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Chesapeake Bay. He looked down and drew my attention to a young woman tying rope to a dock. “It’s a houseboat,” he said, fondly.

I thought of Dempsey’s notion of super-empathy, not only that we are in others, and others in us, despite our different fates, but they are us. And that’s why we never really let them go. Nor they us, even out in the bleachers on a championship night.

We looked at the woman below. She was almost as tall as Jim Loll.

Orfalea is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.