Unplugging at Point Reyes National Seashore, home to a famous lighthouse, pristine beaches and off-the-grid peace

- Share via

Reporting from Point Reyes Nat'l Seashore, Calif. — A handwritten sign in the Bear Valley Visitor Center didn’t offer much hope for a colorful sunset: “99% chance of fog tonight,” it advised, followed by the postscript: “This is likely an underestimation.”

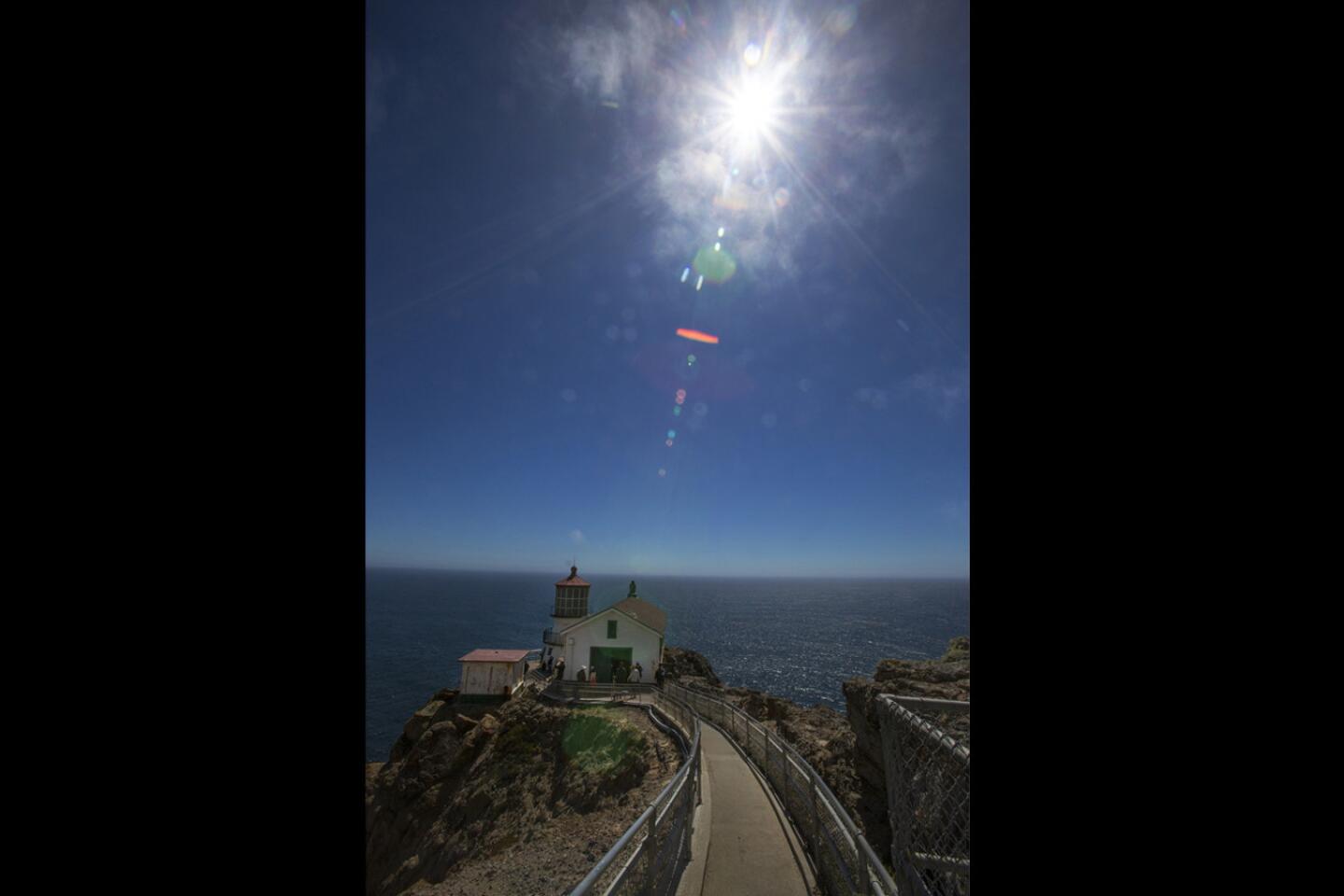

But I’d come nearly 500 miles to see the sun’s bright, hot rays reflected on the facade of the Point Reyes Lighthouse at end of day. I shrugged off the forecast and drove 21 miles to the edge of the continent to take a look.

“It’s clear,” I thought cheerily as I got out of my car in the lighthouse parking lot on a sunny July afternoon. But wisps of fog began blowing across the half-mile trail to the summit. And as I reached the top, a blanket of gray gloom swirled in from the sea, swallowing the lighthouse and the surrounding rocky terrain. My mood became as dark as the overcast sky. There was no way I’d see a sunset tonight.

Celebrating our national parks »

I must admit it was pretty, though, in a fairy-tale sort of way. And true to nature. Point Reyes is the second foggiest place in North America (following Grand Banks, Newfoundland). In fact, the lighthouse was built in 1870 to protect ships from foundering in the fog. I decided I didn’t care about missing the sunset. I was celebrating the 100th birthday of the National Park Service with a visit to a beautiful place, and that’s all that mattered.

Point Reyes National Seashore, a triangle of land north of San Francisco, offers visitors pristine beaches, dramatic waves, rocky headlands, tide pools, marshes, open pastures and forested ridges. Besides being one of the foggiest places in North America, it is the windiest place on the Pacific Coast and home to more than 50 threatened or endangered species. The United Nations has named it an International Biosphere Reserve in recognition of its unique biological communities.

While here, I hiked the beach and forest trails, walked nearly 700 stairs in a round-trip journey to and from the famous lighthouse, spotted humpback whales, elephant seals and Tule elk, and explored a portion of the 80 miles of coastline that make up this protected region, one of 10 National Park units designated as national seashores.

Without the designation, the peninsula here — fewer than 50 miles from a metropolitan area that’s home to 8 million people — may not have fared as well as it has. In 1962, with proposed development threatening the coastal scenery and habitat, President Kennedy signed a bill designating it a park service seashore, joining the likes of Cape Hatteras, N.C., the first such park (1953) and Canaveral, Fla., the last (1975).

Every year Point Reyes, or King’s Point, draws 2 1/2 million visitors, people such as Shelby D’Ambrosi and Gabriel Villasenor from nearby Berkeley, who visited on a summer weekday and found the park uncrowded despite the time of year. “It’s so special to be able to get away from the world and unplug here, to see the ocean and pods of whales,” D’Ambrosi, said.

With about 150 miles of hiking trails to explore, plus 71,000 acres of protected land and 32,000 acres of wilderness, Point Reyes allows visitors to enter a quiet land far from the noise of the city.

Cicely Muldoon, the park’s superintendent, grew up in nearby Marin and loves sharing the off-the-grid solace that can be found here. “You can walk on a wild Pacific beach and hear nothing but the sound of waves and birds. It’s a wonderful place for troubled times.”

Besides the treasures onshore, the offshore waters are considered among the world’s richest. Sunshine, currents and the contour of the seafloor combine to provide a feast for birds, seals, whales and other creatures. Two national marine sanctuaries, Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones, safeguard marine resources.

I went in search of one of those resources during my visit, walking to Elephant Seal Overlook to catch sight of the huge animals, which weigh up to 6,000 pounds and have trunk-like snouts that give them faces only a mother could love.

The seals, once hunted nearly to extinction, visit the park semiannually, lounging on the beach near Chimney Rock, getting some much-needed rest after their 12,000- to 14,000- mile annual migration, the longest of any marine mammal.

As we watched half a dozen seals, a loud sonorous sound filled the air, sort of a cross between a thunderous burp and an off-key air horn. “They consider that sexy, like some men I know,” said Honolulu resident Alyse Prayton, who was standing next to me. Everyone on the overlook laughed.

I decided to try again for a sunset view, driving through the park one more time past farmland — dairy and beef operations have operated here since the 1850s — and stopping to take one last look at some of the beaches: Point Reyes Beach, an 11-mile expanse of shoreline where thunderous waves often can be seen, and Drakes Beach, a curving bay with sand dunes and calm waters. It’s named for explorer Sir Francis Drake, the first Englishman thought to have seen the region.

The afternoon was clear and promising as I parked in the lighthouse lot, but I knew now that the weather here couldn’t be trusted. That was why dozens of ships had smashed into the rocks below the station, and why several lighthouse keepers were said to have gone mad from the storms and isolation.

It was still good as I walked the pathway to the summit. A spectacular view of Point Reyes Beach and the Pacific Ocean spread out before me, with the golden tones of a late-day sun coloring the land, lighthouse and sky. And there was a bonus in the water; three humpback whales were dining on krill or anchovies. I watched them for nearly an hour, their long flippers and humps flashing in the late afternoon light as the sun slid toward the horizon. There wasn’t a bit of fog in sight. And then the big orange ball fell into the sea. A couple of people who had joined me to watch the sunset applauded.

It was worth the second trip. Both the sun and the humpbacks put on a spectacular show.

Tips for visitors

How to get to Point Reyes National Seashore, Calif.

From LAX, you can fly into San Francisco, Oakland or San Jose airports. To avoid downtown San Francisco traffic, fly into Oakland International Airport. From the East Bay (Oakland), follow Interstate 580 west across the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge; take the Sir Francis Drake Boulevard exit, go west on Sir Francis Drake 22 miles until it intersects with Highway 1 at Olema. Turn right on Highway 1; take the first left turn at Bear Valley Road and go west about 1/2 mile. Look for a red barn on the left and a sign for Visitor Center; Headquarters; Information on the right. The park is 30 miles north of San Francisco. If traveling by car from Southern California, it can be approached on winding Highway 1.

Best time to visit: The park is open from 6 a.m. to midnight year-round; the Bear Valley Visitor Center is open on weekends from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and on weekdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. during the spring, summer and early fall. During the late fall and winter it closes at 4:30 p.m. The Point Reyes Lighthouse is open from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Fridays through Mondays: it is closed Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays.

Each season brings different highlights: bird migrations take place spring through fall. Tule elk mating season is late summer and early fall; wildflowers peak in April and May; gray whale migration is from January to April and elephant seals can be found in winter and spring. But nature can be surprising; I saw elephant seals and humpback whales in July.

Sleep

Point Reyes Seashore Lodge, 10021 Highway 1, Olema; (800) 404-5634. The 21-room lodge borders the park; most rooms overlook the three-acre English garden and Olema Creek. Rooms are small but efficient. No TV. Doubles from $155.

Tomales Bay Resort & Marina, 12938 Sir Francis Drake Blvd., Inverness; (415) 669-1389. Several types of rooms, ranging from simple studios facing a parking lot to large bay-front rooms with lanais and fireplaces. Swimming pool. Doubles from $135 to $270.

Eat

Osteria Stellina, 11285 Highway 1, Point Reyes Station; (415) 663-9988. The Marin-chic village of Point Reyes Station has one gas station, a bevy of boutiques and “little star,” a.k.a. Osteria Stellina, a big-city Italian restaurant in a charming little town. Lots of local ingredients, oysters, pasta and pizza on the menu. Entrees $16-$24.

Inverness Park Market, 12301 Sir Francis Drake Blvd., Inverness Park; (415) 663-1491. Specialty and classic sandwiches are the draw at this market deli, which is a fave with locals. You can also find breakfast sandwiches, bagels and lox, and grilled sandwiches. Prices from $4.50.

Station House Cafe, 11180 Highway 1, Point Reyes Station; (415) 663-1515. This friendly village restaurant is a family-run business, offering salads, oysters and other seafood, burgers and veggie entrees. Dinner entrees from $14.95.

Water, water everywhere

The National Park Service protects more than the mountains and forests of the United States. There are 14 lakeshores and seashores that are part of its 412 units.

The four lakeshores are all part of the Great Lakes, and the seashores are predominantly Eastern or Southern. Point Reyes is the only protected West Coast seashore. Here’s a quick look at the 13 others.

National lakeshores

Apostle Islands, Wis. Twenty-one islands and 12 miles of mainland on Lake Superior.

Indiana Dunes, Ind. Fifteen miles of shoreline on Lake Michigan.

Pictured Rocks, Mich. Forty miles of Lake Superior shoreline.

Sleeping Bear Dunes, Mich. Thirty-five of Lake Michigan shoreline.

National seashores

Assateague Island, Va. Barrier island known for its wild horses.

Canaveral, Fla. Barrier island on the Atlantic side attractive to sea turtles, which nest here.

Cape Cod, Mass. Forty miles of beach and 44,000 acres.

Cape Hatteras, N.C. Forty-seven square miles in this, the first national seashore, established in 1953.

Cape Lookout, N.C. Like Hatteras, part of the Outer Banks. 44 square miles.

Cumberland Island, Ga. Georgia’s largest barrier island, with 18 miles of undeveloped beach.

Fire Island, N.Y. Twenty-six miles of shoreline. Includes the home of William Floyd, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Gulf Islands, Florida andMississippi. Barrier islands along the Gulf of Mexico covering about 215 square miles.

Padre Island, Texas. The park service calls this the “longest stretch of undeveloped barrier island in the world.”

Sources: National Park Service, Encyclopedia Britannica

Follow our adventures: Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest

MORE NATIONAL PARKS

Discover our desert national parks and rediscover yourself. You can start with Joshua Tree

10 adventures to pursue in San Francisco’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area

Think you know the Statue of Liberty? Think again

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.