Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Excerpted from “Finding the Words: Working Through Profound Loss With Hope and Purpose” by Colin Campbell with permission of TarcherPerigee, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Colin Campbell, 2023.

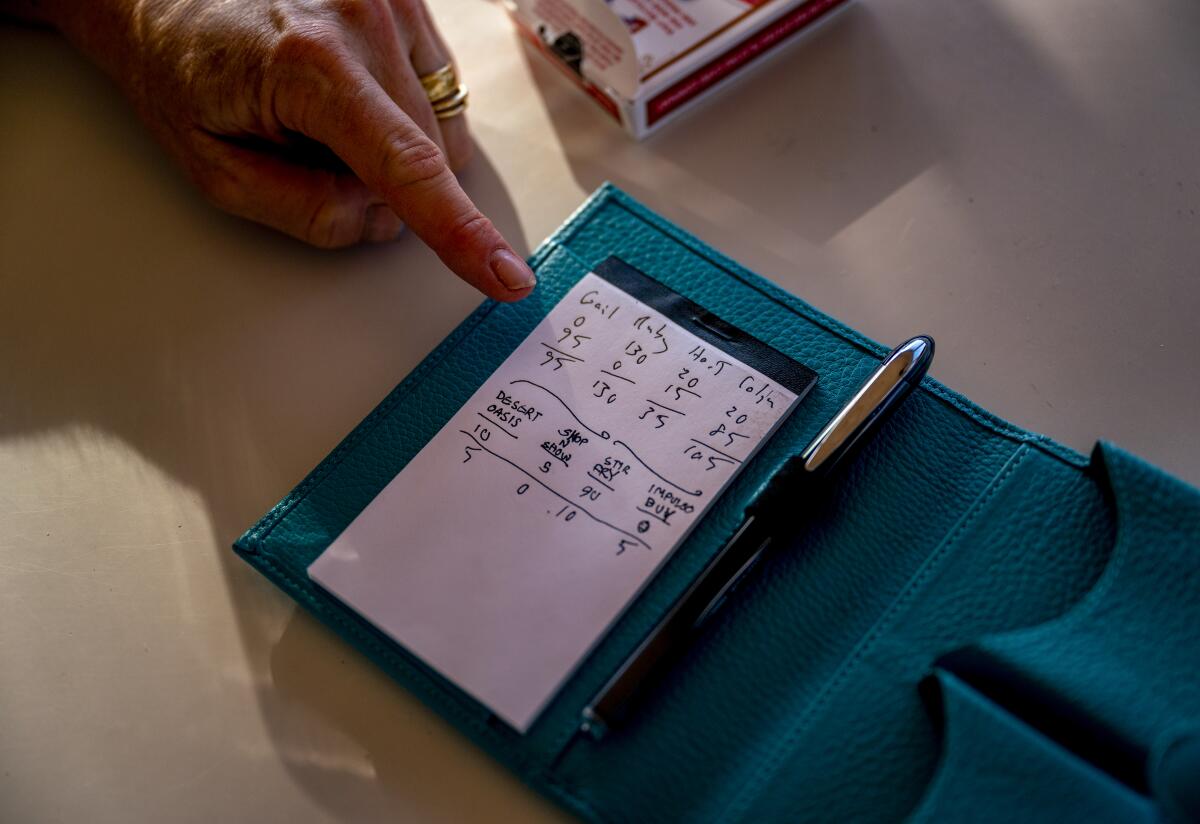

The first week of June 2019, my family spent a weekend in Joshua Tree, which is about 2 ½ hours east of Los Angeles. The four of us — me, my wife Gail, my 17-year-old daughter Ruby, and my 14-year-old son Hart — had such a terrific time in the desert that, on an impulse, we made an offer on a vacation home there: a small, rustic cottage with spectacular views of the valley below and the rocks above.

All four of us loved scrambling on the incredible rock formations in Joshua Tree National Park. We had gone there many times over the years, and the thought of owning a getaway home near the park was suddenly thrilling.

A week later, we were driving back to Joshua Tree because I had lined up meetings with contractors to see about building a pool and an extension on the house so Ruby and Hart could have their own kids’ bungalow. Hart could play video games, and Ruby could have a painting studio with views of the iconic rocks. It was going to be the vacation home of our dreams. At first, I was going alone, but then Ruby insisted on coming along to supervise and then Gail and Hart wanted in. It became another delightfully spontaneous family trip to the desert. We drove out on June 12 at night.

Just after our car crested the steep hill to the high desert, we were struck at a high speed by a drunk driver who already had a misdemeanor DUI conviction.

Ruby and Hart were in the back seat. They were both killed.

Hart Campbell, 14, left, and his sister Ruby, 17, were killed in a car crash in Morongo Valley in June 2019. (Family photo courtesy of Colin Campbell)

The morning after the crash, I was in a horrific stupor, a waking nightmare more agonizing than anything I could have ever previously imagined. After choosing a funeral home and cemetery for my children, I called the real estate agent and canceled the sale. Obviously.

We assumed that we would never go back there. How could we? It would be too painful. And yet buying that house was one of the last things we did as a family. Joshua Tree held countless wonderful memories for us. How could we turn our backs on it when we needed those sweet memories more than ever? Three days after canceling the sale, I called the agent and told him we wanted the house after all. We realized our vacation home could become a grief retreat for us, another place where we could feel especially connected to Ruby and Hart.

A great sense of uncertainty looms when families must decide how — and if — to host a wedding after someone dies. Grief and stress are often compounded by societal expectations.

The problem was this: to get to the house, we had to drive past the crash site on Highway 62 in Morongo Valley. There was no other way to get there. We would have to brave all the terrible traumatic memories of that night if we hoped to get to our desert sanctuary. It felt like the perfect metaphor for the grieving process: if we want to access all the sweet memories and feelings we shared with our loved one, we have to face the full pain of our loss.

As we moved through the first months of early grief, Gail and I were continually confronted by the pain of everything we had lost. Everywhere we looked, we were reminded of Ruby and Hart’s agonizing absence. Every morning there was no one to greet and make breakfast for; every evening there was no one to kiss goodnight. Every spot in our house held their memories. So did every corner in the neighborhood. All our favorite restaurants and parks and beaches were suddenly hard to visit. Even our friends and family reminded us of our kids. Everywhere we turned, we were struck by the pain of our loss. A part of us wanted to retreat to our bed and shut the whole world out. A part of us wanted to die rather than face the agony of our grief.

Our instincts tell us to run from pain. But what if, in the case of grief, our instincts are wrong? After all, the reason it hurts so badly is because we love them so much. The pain is from love. If we look at it that way, the pain can be understood not as a bad thing but as a beautiful tribute. The love and the pain are forever entwined. We can’t have one without the other. If we run from the pain, we’ll also be running from the love we shared. And what if, instead of simply enduring the pain of our loss, we actually seek it out? What if we lean into the pain to bring ourselves closer to our loved ones?

The first time going back to Joshua Tree was terrifying. It took us two months to build up the courage. I had to ask John, my brother-in-law, to drive. I was shaking, my whole body clenched, as he drove us. Gail warned us that at any moment she might need us to turn around and go back home. We drove in terrible silence. As we approached the site of the crash and prepared to pull to the side of the road, a large truck ahead of us suddenly hit its brakes and swerved to the right, almost cutting us off. John had to veer into the next lane just as traffic was whizzing past. His knuckles were white as he clenched the steering wheel. His arms were sore for days afterward.

A reader asks: ‘How do you help a spouse struggling with the recent death of a parent? When do you encourage therapy, (or) further help?’

There was a small memorial by the side of the road that had been put up by a local teenager. It was a wooden cross painted light blue with a short message that read “Beautiful Angels 061219.” We got out and stared at it. It was beautiful and awful; a gesture of love on the side of a hot, grimy highway as traffic raced past in the blaring desert sun. Is this really where our kids died?

Once we finally made it to the house, we weren’t exactly relieved. It was hard standing where, only a few months earlier, we had stood with Ruby and Hart, full of so much hope for the future.

But then we went for a hike in the rocks above our new property and we felt the kids’ presence. It was almost as if we could see them up ahead, scrambling over the boulders. They had never had the chance to climb these specific rocks, and yet it felt to me as though all four of us had been there before. Climbing over those rocks allowed us to connect with Ruby and Hart if only for a few moments.

That first visit to the Joshua Tree house was extraordinarily difficult. But we knew we had to get through that first time to slowly acclimate to the pain. Gail and I have since been back to the house in the desert many times. It has, indeed, become a sanctuary. It is a sacred place to us, where we feel extra connected to our kids. And every time we go, we drive past the crash site. I blow them kisses, and I ache for them, and sometimes I cry. But I am grateful that we were able to incorporate both the house and the site of the crash into the fabric of our lives. I am so glad we ignored the impulse to never go back there again.

We used fashion as a form of communication for my daughter. The outfits spoke for our rock-star warrior who couldn’t speak for herself.

Every one of my connections to Ruby and Hart causes me some pain. I pay a price every time I look at a photo or hear a favorite song or recall a memory or spend time with their friends. But it seems to me that over time, I am able to access more of the joy and feel less of the pain. It feels a little like exposure therapy. Ruby struggled with an obsessive-compulsive disorder. The primary therapeutic process used to treat OCD is to gradually expose the patient to their worst fears. The idea is to have the patient slowly become more and more comfortable tolerating their own distress. Over time, the patient essentially grows less fearful of their own fears. By repeatedly exposing myself to the emotional pain of my grief, I have grown less fearful of it.

It’s often said that time heals all wounds. I think that’s a fantasy. The deaths of Ruby and Hart will hurt me for as long as I live. I will always ache for them. But my relationship to the pain of this wound has definitely changed. A wise friend of ours suggested that maybe grief starts out as a terrible weight that presses down on us, but then, as we slowly process our loss, the pain shifts, slides down off our shoulders and becomes something that moves alongside us. The pain never goes away, but it becomes more bearable. It accompanies us, just as the memories of Ruby and Hart will always accompany us. The pain and love go hand-in-hand. Or as C.S. Lewis once said, “The pain I feel now is the happiness I had before. That’s the deal.”

Pain is a natural, necessary part of grieving. Normally, the body shrinks away from hurt because it is a signal that something should stop — stop touching that hot pan, stop stepping on that sharp spike and so on. But in grief, the hurt is productive and necessary. It is a beautiful sign that our heart is working. We are processing a profound loss and mourning a loved one.

In a densely populated Watts neighborhood desperately lacking green space, a Los Angeles garden is designed to facilitate healing and honor loved ones lost to violence.

I believe I am able to stay close to so many of my friends and I am able to remain creatively productive because I have not shied away from the pain of my loss. More important, my marriage to Gail has remained strong, honest and loving despite our catastrophic loss. That’s largely due to our shared practice of leaning into the pain. I also think embracing the pain has enabled us, on a daily basis, to think about and take solace in the love we shared with Ruby and Hart.

I don’t mean to imply that mourners ought to spend the rest of their lives in nonstop pain. It’s not about punishing ourselves or confusing pain with love. The reason I am in such pain is because my love was — is — so deep. In that sense, my pain is a reflection of my love. But that does not mean that pain equals love. I don’t need to be in constant agony to prove it. I am not condemned to expressing my love for Ruby and Hart solely by the degree to which I am suffering. My love is found in the joy I feel as I think about the beautiful life I shared with my children.

Paradoxically, I lean into the pain of my grief precisely so that I can then be able to let that pain go and access the happy memories instead. I am not trying to wear my pain as some kind of badge of honor or proof of my love. Being in pain is not the goal of grieving. Ruby and Hart don’t want me writhing in pain; they want me to hold on to all the joy they gave me in life. Of course, like all things about grieving, it’s easier said than done.

Gail and I built that pool for our house in Joshua Tree, after the crash on the exact spot where Ruby said we should. Now I swim laps and I ache for Ruby and Hart. And I also try to simply enjoy the pool. I savor the memories but I also make new memories. I try to continue to forge a life worth living, even though it has to be one without Ruby and Hart. I try as best I can to hold joy and pain in the same hand.

Campbell is a writer, director and professor of theater and film living in Los Angeles. He is the author of “Finding the Words: Working Through Profound Loss With Hope and Purpose,” which was published earlier this year. He and his wife, Gail Lerner, started the Ruby and Hart Foundation in honor of their children who loved books. Campbell is on Instagram: @colincampbellwriter

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.